Relationships • Sex

The Ongoing Complexities of Our Intimate Lives

In sexual matters, the world became modern in early April 1953, on a beach in Cannes, when the eighteen year old Brigitte Bardot appeared in front of the world’s press to promote her new film, Act of Love (co-starring Kirk Douglas). She was dressed in a small floral bikini, an item of clothing until then seldom seen on camera (it was illegal to show belly buttons on American screens until 1961) and condemned only the year before by Pope Pius XII as liable to promote sin and impede virtue.

Brigitte Bardot, Cannes Film Festival, 1953

The French designer Jacques Heim had invented the bikini in 1946, days after the United States had begun nuclear testing on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall islands. He had chosen the name because he predicted that his invention would prove as explosive as a hydrogen bomb. Though it took until Bardot and Cannes for the fuse to light, the bikini and all it stood for did indeed launch a new era. Women around the world shed their old one piece costumes and many of the bodily attitudes that had gone with them. In 1960, Brian Hyland had a hit with his song ‘Itsy Bitsy, Teenie Weenie, Yellow Polka Dot Bikini,’ bikinis were center stage in the hit film Beach Party of 1963 and again in Bikini Beach of 1964. The Catholic Church gave up the fight, as did film censors and conservative groups. Within a few decades, the bikini seemed always to have been part of a normal – that is, ‘liberated’ – existence.

U.S. President George W. Bush with members of the U. S. Women’s Beach Volleyball team in their bikini uniforms at the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

The bikini was not, of course, just an item of clothing. It represented a particular approach to the body and to sexuality: one free of shame and guilt, without the legacy of an embarrassed and repressed past and a herald of exuberance and ease. The bikini reconnected modernity to the pagan freedoms of the Ancient Romans and Greeks, who had in their statues, mosaics and Olympic games known how to feel proud of the body’s beauty and athleticism.

Early bikinis: Roman mosaics found in the Roman Villa of Romana del Casale in Sicily.

It was Christianity that separated Brigitte Bardot from the Romans. The church had waged war on the body for hundreds of years, associating nakedness with the sins of Adam and Eve and making our shame feel like a punishment for the transgressions of our ancestors. That many of us might feel extremely uncomfortable at the sight of our flesh was simply evidence of a fundamental fact about human beings: that we are the descendants of sinners.

Masaccio, The Expulsion of Adam and Eve, 1424

Those rare pre-Moderns who had dared to try to enjoy a less hampered relationship with their sexuality and their bodies had had to look far beyond Europe’s borders. The French nineteenth century painter Paul Gauguin, after spending a few months in Provence a few hours from Cannes, had turned to Tahiti for the paganism that his own prudish country evidently could not provide. Far away from Europe’s top hats and long dresses, he found people who were comfortable sitting under tropical trees in Edenic nudity, apparently without any conception of physical embarrassment.

Paul Gauguin, Te nave nave fenua / The delightful land, 1892

But by 1953, there was no longer a need to go so far. Tahiti had come to France.

The attempts of the pre-modern world to deal with sexuality can appear, from the post-Cannes world, painful in their degree of evasion, subterfuge and gingerliness. When nineteenth century doctors first began recommending trips to the seaside on medicinal grounds, the efforts required by women to get themselves into the water without showing their bodies to strangers were as technically impressive as they were psychologically absurd. Horses would be used to drive special huts on wheels into the water, inside which women could open a hatch to lower themselves for a bathe. To glimpse so much as a woman’s elbow or shoulder would have been thought a rank indecency.

Such contortions were underpinned by a view that sexual desire was the enemy of a sane or good life. It was a species of insanity set within us to tempt and torture us, to derail our sensible routines and to sicken us at ourselves (‘Illico post coitum cachinnus auditur Diaboli’; ‘After copulation, the devil’s laughter is heard,’ ran the adage). Except for those very rare moments when one was planning to make a child, sexual activity had no place within a dignified existence. What we thought about and did in its name was bestial. Artists and philosophers described battles within each good person between desire on the one hand and chastity on the other. No one could be spared such perpetual civil war, but the moral among us knew which way to settle the issue.

Gherardo di Giovanni del Foram, The Combat of Love and Chastity, 1475

The Renaissance philosopher Marsilio Ficino described two kinds of love. Amor Divinus or Divine Love, united man with the creator of the universe; it inspired gratitude, benevolence, selflessness and devotion to reason. But Amor Ferinus or Bestial Love was a means to perpetual masturbation, exhaustion, debasement and perversion. The purpose of philosophy was to persuade students to shift their interests from the latter to the former. But one was left in no doubt as to the scale of the challenge. Sexual desire was framed as a cataclysmically powerful force that could lay waste to the best prepared plans and the deepest forms of virtue. Aristotle, widely reputed to have been the wisest man of antiquity, was in the Christian era (apocryphally) said to have fallen in love with Alexander the Great’s wife Phyllis, who punished him for his desire by making him crawl around naked on all fours with a leash in his mouth – to prove to the unwary just how much stronger lust could be than reason.

Hans Baldung, Phyllis riding Aristotle, 1515

Venus, Roman goddess of love, was viewed in Christian times not as the charming embodiment of playful desire she had previously been known as – but as a notorious temptress who could shatter the resolve of the sternest minds whom she had cast her spell on. In a painting in the Louvre from the early 15th century, Venus’s vagina is shown emanating rays that simultaneously blind the eyes of six great men: Achilles, Tristan, Lancelot, Samson, Paris and Troilus. It might be very hard to look away; it was even more dangerous not to try.

The priority for all those educating the younger generation was to help them to make the right choices in the battle between vice (almost always a beautiful woman) and virtue (almost always a decent but vacillating man).

Paolo Veronese, Allegory of Virtue and Vice, 1565

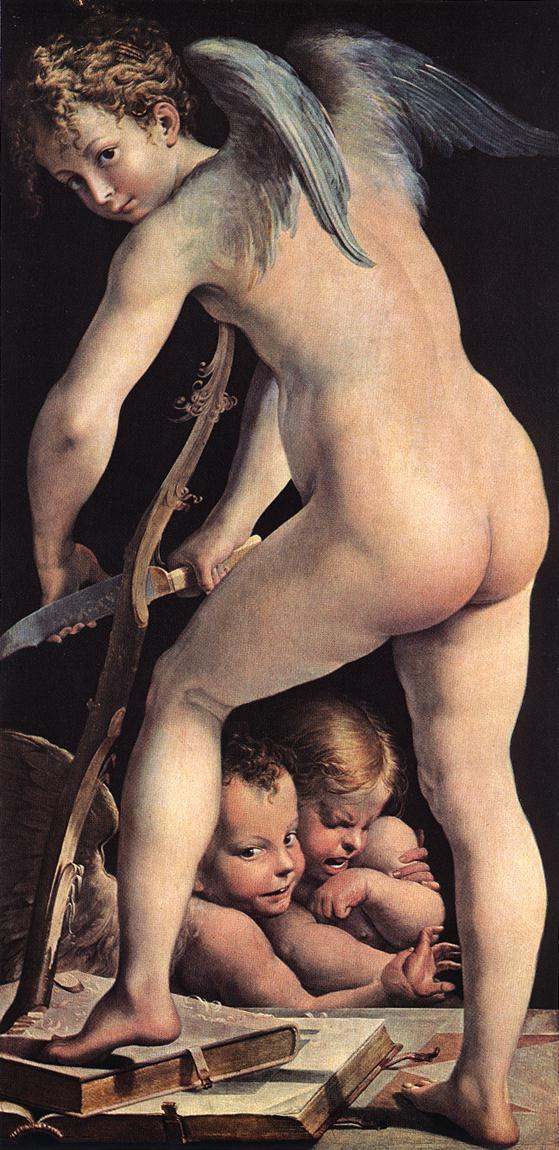

But even in ostensibly good people, there always lurked somewhere the risk of falling under the influence of the seductive but evil Cupid, never far away and ready to fire his arrow and destroy the best of our intentions. For many centuries, desire wasn’t something to enjoy or delight in; it was invariably a trap and possibly a death sentence.

Parmigianino, Cupid Marking his Arch, 1533

To this grim assessment of desire in philosophy and art, nineteenth century medicine added a further forbidding layer. In the eyes of the Austrian psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing, sex may not directly have been the work of a devil or a devious cupid, but it might as well have been given what it made us do: in his landmark work Psychopathia Sexualis (1886), the most influential book on sex in Europe in the nineteenth century, von Krafft-Ebing focused on the multiple perversities and sicknesses that sex inspired. Though written in sober, detached prose, the book couldn’t hide its distaste at the nature of sexuality: ‘Love unbridled is a volcano that burns down and lays waste all around it: it is an abyss that devours all—honour, substance and health,’ noted von Krafft-Ebing in his introduction, then went on to outline hundreds of case studies of the painful and off-beat compulsions bred in us by our sex drives. For example:

Case 1: Mr Y, always given to indulgence in sensuality but always with regard for decorum, had shown, since his seventy-sixth year, a progressive loss of intelligence and increasing perversion of his moral sense. Previously bright and outwardly moral, he now wasted his property in concourse with prostitutes, frequented brothels only, asked every woman on the street to marry him or allow coitus, and thus became publicly so obnoxious that it was necessary to place him in an asylum. There the sexual excitement increased to a veritable satyriasis, which lasted until he died. He masturbated continuously, even before others; took delight only in obscene ideas; thought the men about him were women, and followed them with indecent proposals.

CASE 59. X., a model husband, very moral, the father of several children, had times—i.e., attacks—in which he visited brothels, chose two or three of the largest girls, and shut himself up with them. He bared the upper portion of his body, lay down on the floor, crossed his hands on his abdomen, closed his eyes, and then had the girls walk over his naked breast, neck and face, urging them at every step to press hard on his flesh with the heels of their shoes. Sometimes he wanted a heavier girl, or some other act still more cruel than this procedure. After two or three hours he had enough. He paid the girls with wine and money, rubbed his blue bruises, dressed himself, paid his bill, and went back to his business, only to give himself the same strange pleasure again after a few weeks.

Sigmund Freud, von Krafft-Ebing’s successor, may not have been quite so grim, but there was a similar atmosphere to be found around sexuality in his work: in his patients as well, sex was for the most part dark, compulsive, extremely strange and a disruption to everything we might seek in a civilised and moral life.

How refreshing was Brigitte Bardot by comparison; how far from the dark analyses of those two great Austrian doctors or the finger-wagging warnings from Renaissance painters or the dire admonitions of the philosophers. She represented lightness, innocence – and a return to Eden. Modernity had helped us to fly through the air, cure polio and make calls to other continents; it would also help us to feel natural and happy in bed. We were – as modern people – finally to be ‘liberated’ from hundreds of years of regrettable hangs up and fears, apprehensions and sorrows.

The modern age imagined itself to be supremely helpful. Volleyball on the beach in a bikini certainly sounds preferable to being trodden on in a brothel. But arguably, modernity has complicated rather than eased our relationship with sex. The old world knew that sex was difficult. It had no qualms about admitting that it could be embarrassing, that it might make one do things one would regret, that it stood in opposition to certain dignified ideals, that it might be in conflict with love, that it might inspire self-disgust and that one might want to take sensible precautions not to be turned on and not to excite others, for fear of the consequences. These were basic truths taken for granted by all, and though they were certainly melancholy, in many ways they created a helpful backdrop against which each of us might navigate and mitigate their own sexual urges.

The bikini view of sex, though extremely well-intentioned, may by contrast leave us ill prepared for many of the realities of living with a sexual drive. It finds it hard to admit that sex can – for most of us at some points – stand in direct opposition to anything that seems clean, kind and jovial: it may inspire in us a desire to flog, to debase, to insult, to be roughed up and to say and do things that are directly contrary to a reasonable self-image. By implying that sex should be ‘normal’, the sunny view can leave us more alone, more confused and more abnormal at those times when sex clearly isn’t straightforward, when we find ourselves – as many of us will – craving activities which have no place in a sensible assessment of human nature, and that while they may not be ‘sinful’, are certainly dark and peculiar. Nor does the modern bikini view of sex properly take on board how often desire can be separated from love; how likely it is that – after a while – the person one loves will no be longer the person one wishes to sleep with and how much strangers, even strangers one might hate or dislike, can compell us to take risks we regret the moment after we have appeased ourselves. The modern view of sex gives us no reassuring narrative about the dark normality of off-beat activities. It doesn’t imply, as those grave Austrian doctors did, that all sex is slightly mad and that we should be well prepared for the fact on our wedding days, rather than taking the complexities as some exceptional personal affliction when they develop, as they inevitably will, in the course of ordinary monogamous relationships. The old world made it hard to discuss sexual issues. The modern world has made it far easier to banter about them; we are happy to share details of our conquests and lusts. But we are in no better position to bring up the truly strange sides, the guilt, the fetishes, the very indecent thoughts. Indeed, we may be in a worse position, precisely because we are meant to have been liberated, we are meant to be over the embarrassments and the trepidation. We are meant to be moderns, clean, vigorous and cheerful. And yet in our hearts, many of us are quietly going out of our minds with sexual aches and experiences that feel as out-of-bounds as anything a medieval monk might have gone through.

Sex will always be too potent and too radical a force to be so-called normal. It is inherently transgressive – and has to be so in its very structure. The wisest attitude may be to assume that we cannot return to Eden, and to be hugely suspicious of any narratives of carefree or prelapsarian desire, be they from Tahiti or Ancient Rome. The working assumption should be that sex has to be difficult, perhaps no sin, but certainly a very heavy burden: a dynamic at odds with all the sensible other things we are trying to do, like manage a career, raise children, or simply love someone else kindly and with respect over many decades. The future of sex lies less in imagining that it can be rendered simple and innocent, as in acknowledging its inevitable oddity and preparing for it with courage and dark humour. Cupid isn’t directly firing arrows into us to lead us astray, but there are drives at play in us that will take us shockingly far from where we might want to be if reason were wholly in control. We need a new language in which we can own up to how outlandish and frightening, mesmerising and wicked, sex is and will always remain. That would be true liberation.