Work • Capitalism

Nature as a Cure for the Sickness of Modern Times

The modern age has manhandled nature like none before it ever quite has. Previous eras may not have treated it with too much respect – the Ancient Greeks stripped most of their coastline of trees by late Antiquity, the Romans deforested large chunks of North Africa and killed off all its larger wildlife for food and gladiatorial fights (the Roman historian Pliny lamented how the nobility had destroyed Africa’s elephants to feed their appetite for ivory bedsteads). But the old world lacked the new one’s sheer relentlessness, as well as its dynamite, power saws, pesticides, guns and processing plants.

As the railways cut through the American continent, nature was hacked down with unsurpassed thoroughness. There’d been 25 million bison in North America in the 16th century; there were fewer than a hundred by the end of the nineteenth century. There’d once been a billion trees across the continent; by 1900, 85% of them were gone.

1892: bison skulls await industrial processing at the Michigan Carbon Works, Detroit. Bones were processed to make glue, fertilizer and ink.

A forest being cut down on the way between New York and Akron, Ohio. James F. Ryder, Atlantic & Great Western Railway (1862). National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Across modernising countries, people knew something important was being lost and many urgent attempts were made to slow the extinctions. The Yosemite valley was protected by Abraham Lincoln in 1864, Congress established Yellowstone National Park in 1872; President Wilson created the National Park Service in 1916. In England, the Lake District was protected by legal force in the late nineteenth century, in Australia, the Royal National Park was established south of Sydney in 1879, Switzerland created the first European National Park in 1914. On a smaller scale, most modern cities created free parks for their inhabitants: Munich’s Englischer Garten was founded in 1789, London’s Victoria Park was established in 1845, Lincoln Park in Chicago opened its gates in 1865, Central Park in New York was completed in 1876.

When trying to justify why nature might be so important, there was always one answer put forward by promoters of national and urban parks: industrial society, with its factories, crowded streets and tightly packed tenement blocks made it imperative for people to have a chance to get out into nature for fresh air and for exercise. Trees and habitats had to be preserved so that we could keep fit.

Though self-evident, something else – less often mentioned and harder to put a finger on – was also at stake: the idea that nature might be highly necessary for what a few voices were still daring to call our ‘souls’, and others more plainly our psyches. It seemed that nature was as important for treating the psychological ills bred by modernity as it was for addressing its physical ones. Modernity had made us mentally unwell – and nature held some of the cures.

What then might the therapeutic benefits be? At least five themes suggested themselves:

Recalibration

As European pioneers began cutting and shooting their way across the American continent in the early nineteenth century, one unlikely figure, a minor French-American businessman called John Audubon, followed in their wake. He wasn’t after land, gold or bison hides. He was interested in birds, with which he had been fascinated since his childhood in Brittany – and had announced his intention to draw every species in America. In the end, he managed only 435 (there were 2,000 in total), which he etched on large copper engraved plates and collected together in one of the most successful books of the nineteenth century, The Birds of America, published between 1827 and 1838 (Queen Victoria had a copy, as did France’s Charles X and American President James Polk).

John Audubon, Mallard Duck, 1838

Many of Aududon’s birds were extremely rare and unlikely ever to be seen in the wild by his audience. But one of his most popular illustrations was also of one of the most common of all birds: the mallard duck. Mallards, with their bottle-green heads and white collars, are an immediately recognisable sight to almost anyone who has ever sat on a bench in an urban park in Europe or North America. Despite its ubiquity, it can be highly therapeutic to encounter one. Part of what makes them such a welcome sight is how entirely indifferent they are towards all of what and who we are. They’ll paddle around us beside us, looking out for dragonflies or worms, without fear or favour. Everything that we may think of as important, everything that agitates and stirs us, makes us feel shame or evokes longing, is of no concern whatsoever to a mallard. We may be an important person in society or one of the most insignificant or maligned, that is of no matter to the duck, who will as willingly take a bit of stale bread off the hand of a senior judge as off a convicted felon. The mallards care nothing for our turbulent histories, the dramas in our governments, the reversals in our economies, the shocks in the lives of our famous actors. Things have been progressing in pretty much the same way for centuries for them; the loss of the American colonies or Napoleon’s rout at Waterloo weren’t of any concern and nor are whatever emotions happen to be roiling and tormenting us today. It could appear lonely to face such aloofness, it is in fact the greatest relief from the agony of life in the human beehive, where everything that we say or do, all the gossip about us, our striving for reputation and our wounded pride, consume so much of our nervous energy and stir us in our uneasy nights. By enmeshing ourselves tightly with other humans, we don’t only cut ourselves off from fresh air, we deny ourselves the experience of ‘otherness’, of creatures who can put our own melodramas into perspective via their haughty disregard for our existence – and their laser-like focus on their own, utterly contrasting priorities. Walking down a modern urban thoroughfare, the throb and dynamism of our benighted race is constantly on show. Our thoughts are drawn to what we haven’t yet achieved and what we still so badly want. The adverts implore us to shift our desires, the news enrages and perturbs us, information about our colleagues and acquaintances inflame our competitiveness. At this point, the mallard duck isn’t just another half-way interesting creature to spot while taking a pause on a walk. It’s a pillar of truth waiting for us, in one of the ponds in Victoria Park or Lincoln Park, the Englischer Garten or Central Park, waiting to tell us something that almost nothing and no one else will in the large city: that not a thing about us, good or bad, lamentable or beautiful, is of any interest at all to anyone outside our own vainglorious bubble. In short, and very thankfully, that we don’t matter – one of the most generous, kind and necessary messages that anyone in modernity could ever hope to hear.

A ten minute walk from the Lustgarten and the relief of a mallard: Paul Hoeniger, Spittelmarkt, 1912.

Necessity

Modernity is founded on the notion that we can – through willpower and ingenuity – change our circumstances. We can divert rivers, transform our fortunes, invent miraculous machinery or start new lives on other continents. But imagine for a moment a tree in autumn, a large tree, an oak or an aspen. It might be late October in a mild year. For a long time, the leaves held out but now they are properly turning, a tell tale silvery grey or ochre tinged with auburn – and within a few weeks and one or two vicious storms from the east, they will be gone, two hundred thousand of them blown around the forest floor, where millipedes, maggots, slime moulds, earthworms and bacteria are waiting to decompose them into primal mulch. Nothing can stop the melancholy process. All summer the leaves protected us, filtering the harshness of the bright sunlight and casting gentle criss cross patterns as dusk fell. In spring, the leaves’ appearance was a symbol of hope and new beginnings. Now the air smells of death and decay. Our lives are no less subject to the laws of nature than are trees. We too are born, develop and must die. There are autumns in our years that nothing can protect us from. But it can be by contemplating the ineluctable processes of growth and decay in nature that we may come to accept more serenely all that we will have to give up and see taken from us with time. There are laws of nature that we can’t resist, that no amount of machinery or eloquence or money or power will overcome. An emperor and a tycoon are as vulnerable as a tramp before the mechanisms of the natural world, who will grind each one of us back down to our cellular origins. It could sound merely tragic – but there is relief from the manic assertiveness of our egos within the grand spectacles of nature. The majestic trees render what might have been a mere humiliation into a call for a noble surrender before an awe-inspiring adversary.

In 1853, the American painter George Inness received a letter from the president of the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad Company, who was extremely proud of a new line that he and his team had cut through pristine nature to connect up Buffalo with New Jersey. He asked Inness to emphasise the sweep of the railway track and the scale of the roundhouse. But Innes wasn’t so sure of these priorities. He was very fond of trees – their stature and their elegance, but most importantly, their philosophical wisdom. Which is why, when he came to paint his The Lackawanna Valley (1855), he included so many incongruous tree stumps in the foreground of his picture. A civilisation that was more excited about the arrival of a train than the end of nature had forgotten its priorities. It was also a civilisation steered by people at risk of forgetting that they too were still subject to natural laws, that even if they could now reach town in a few hours to buy a hat or transport a wagon of coal, they could not hide from the limitations imposed on all living things. It was perhaps in the end no surprise that those trees had been so impatiently cut down. They had been speaking too loudly of the vanity of all things – to some possibly rather vain railway men.

Ataraxia

The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche spent seven summers – in 1881 and again between 1883 and 1888 – in the high Alpine village of Sils Maria in the south east corner of Switzerland. He rented a room in a modest farmhouse where – far from the crowded cities and turbulent urban passions that he feared – he wrote some of his most famous works, including The Gay Science, Thus Spake Zarathustra and Twilight of the Idols. He would get up very early, and write until early afternoon, at which point he would go out for a two to three hour walk – which was where he grew familiar with the grey-brown mountain cattle known as the Braunvieh. Groups of them were to be found in most pastures, and Nietzsche fell in love with them. He was fascinated by the patient, wise-looking way they dealt with their often less than ideal lives. They didn’t show any impatience or anger. They didn’t appear to suffer from envy or regret missed opportunities. They seemed to harbour no plans for revenge or cower fearfully from the future. They behaved calmly in rain and sunshine, when flies landed on their noses and their heavy bells chafed their necks. Nietzsche felt that they had reached the state of calm and equanimity that had been the goal of all philosophy for the Ancient Stoics, a frame of mind known to the Greeks as ‘ataraxia’. They might not have read too much Zeno or Seneca, but they were true philosophers. Nietzsche gave them a staring role in his own philosophy in Thus Spake Zarathustra: ‘Unless we change (or be converted) and become as cows,’ he wrote, ‘we shall never enter the kingdom of heaven.’

Wonder

It can be easy to feel bored and listless in modern times. The truly exciting things are often financially and practically out of reach. Nothing about our lives may feel as exciting and as special as it should; we still lack so much. We didn’t start like this. Once we were three years old and everything was amazing: the lightswitch, the zip on our jacket, the way a door closed. Since then our enthusiasm has dropped, but encouragements not to lose a taste for existence abound in the spectacle of nature. Granted; we have not been invited to certain parties, and our job is feeling repetitive – but right now, across parts of Asia and Australia, colonies of weaver ants are building their nests, some of the oddest and most impressive structures that exist. Implausible numbers of these ants, into the many hundreds, will stand with military precision on the edge of a large leaf, and collaborate with others to draw a neighbouring leaf to it with the help of strands of larval silk. They will then harmoniously and diligently sew the two leaves together with their silk thread, building up sealed and watertight structures the size of a human head or larger, in which they set up their meticulously ordered colonies. We can get bored because we are in a tunnel which we’re mistaking for an open view. We can feel like we have explored everything we need to know. But we have only to recall that things are far weirder and more stupefying than we ever tend to think in the city – because we are sharing the planet not only with people we went to school with and high powered television executives but also flying squirrels, hyacinth macaws, vampire crabs, glasswinged butterflies, french angelfish, nicobar pigeons, okapis, rock agamas and tokay geckos – all of whom contribute to a gigantic call for us to take another closer, more wondrous and more enchanted look at what breathes around us.

Modesty

One of the more curious features of the modern age is that it coincided with an explosion of interest in flowers. By the 1890s, in the suburbs of both London and Paris, it was estimated that three quarters of householders were actively engaged in tending to their gardens. The most popular flowers were lilies, daisies, lilacs, tulips and daffodils. Talk of growing flowers is apt to seem ridiculous to most people under thirty. There are surely more exciting and substantial goals to set our eyes on than the gestation of small colourful temporary bulbs – when, for example, we have romantic love to explore or professional life to succeed at. But it is almost impossible to find anyone over 70 who does not care for gardening. By then, most people’s ambitions will have taken a substantial hit: love or work will not have worked out in key ways. At which point the consolation offered by gardening starts to feel very significant indeed. Flowers become something to be cherished precisely because of their lack of exigencies or overt grandeur. The world beyond will always resist our efforts to bend it to our will, but in the garden, with effort, regular watering and some luck with the sun, we can for brief weeks be the midwives to something as visually seductive as it is consoling. We are moved by the flowers’ tender beauty because we know, by this stage, so much about pain and disappointment; we aren’t sentimental so much as traumatised. We won’t turn down this one of nature’s gifts. It isn’t the largest, but it may – on a mild summer evening – be very much enough.

**

Those who have wished to protect nature from modernity’s destructiveness have often made powerful appeals to people’s altruism; they have evoked the suffering of other species and the needs of as yet unborn generations. But it is rarely a winning strategy to try to get through to the selfish by appeals to their conscience; it may simply be wiser to target their self-interest. We don’t need to make impassioned speeches begging the drillers and the loggers to be good. We need only point out the cost to themselves, and more specifically to their mental well-being. There may be other ways to get healthy besides going to the park, but it is hard to imagine a species maintaining even a semblance of mental equilibrium without, somewhere in the picture, some very mighty trees, a mallard duck – and a team of weaver ants.

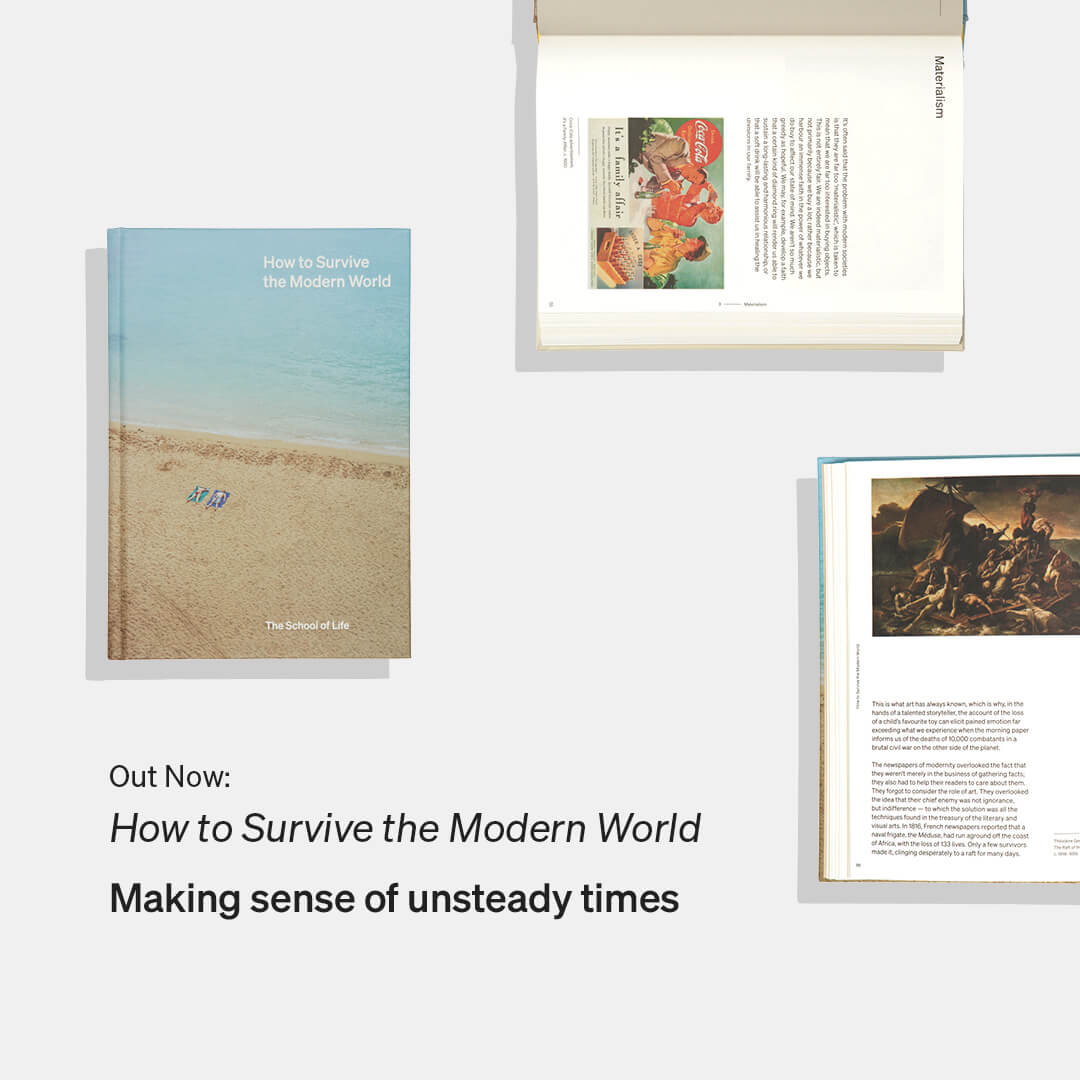

How to Survive the Modern World

New Book Out Now

How to Survive the Modern World is the ultimate guide to navigating our unusual times. It identifies a range of themes — our relationship to the news media, our assumptions about money and our careers, our admiration for science and technology and our belief in individualism and secularism – that present acute challenges to our mental wellbeing.

The emphasis isn’t just on understanding modern times but also on knowing how we can best relate to the difficulties these present, pointing us towards a saner individual and collective future.