Work • Sorrows of Work

Why Modern Work Is So Boring

One of the overriding reasons why modern work is so boring is that we keep having to do more or less the same thing every day. We have to be specialists, whereas we would – deep in our hearts – surely be so much more fulfilled if we could be wide-ranging, endlessly curious generalists.

You can understand the origins of restlessness when you look at childhood. As children, we were allowed to do so much. In a single Saturday morning, we might put on an extra jumper and imagine being an arctic explorer, then have brief stints as an architect making a Lego house, a rock star making up an anthem about cornflakes and an inventor working out how to speed up colouring in by gluing four felt-tip pens together; we’d put in a few minutes as a member of an emergency rescue team then we’d try out being a pilot brilliantly landing a cargo plane on the rug in the corridor; we’d perform a life-saving operation on a knitted rabbit and finally we’d find employment as a sous-chef helping make a ham and cheese sandwich for lunch.

Each one of these ‘games’ might have been the beginning of a career. And yet we had to settle on only a single option, done repeatedly over 50 years. We are so much more than the world of work ever allows us to be. In his ‘Song of Myself’, published in 1855, the American poet Walt Whitman gave our multiplicity memorable expression: ‘I am large, I contain multitudes’. By which he meant that there are so many interesting, attractive and viable versions of oneself, so many good ways one could potentially live and work. But very few of these ever get properly played out and become real in the course of the single life we have. No wonder if we’re often conscious of our unfulfilled destinies – and at times recognise with a legitimate sense of agony that we really could well have succeeded very well at doing something else.

It’s not our fault that we have not been able to give our ‘multitudes’ expression. The modern job market gives us no option but to specialise. We cannot be an airline pilot one afternoon a week, a tree surgeon two days a month, a singer-songwriter in the evenings, while holding down part-time jobs as a political advisor, a plumber, a dress designer, a tennis coach, a travel agent and being, additionally, the owner of a small restaurant serving Lebanese mezze – however much this might be the ideal arrangement to do justice to our widespread interests and potential.

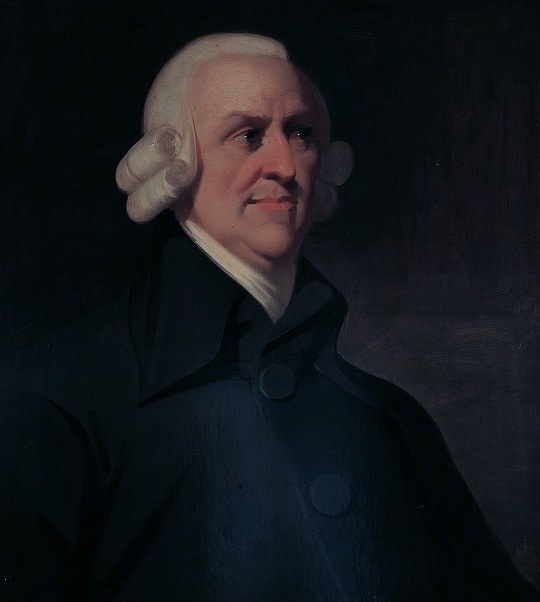

The reasons why we cannot do so much were first elaborated at the end of the 18th century by the Scottish philosopher Adam Smith. In The Wealth of Nations, Smith explained how what he termed the division of labour massively increases collective productivity. In a society where everyone does everything, only a small number of shoes, houses, nails, bushels of wheat, horse bridles and cart wheels are ever produced and no one is especially good at anything. But if people specialise in just one small area (making rivets, shaping spokes, manufacturing rope, bricklaying etc) they become very much faster and more efficient in their work and collectively the level of production is greatly increased. By focusing our efforts, we lose out on the enjoyment of multiplicity – yet our society becomes overall far wealthier and better supplied with the goods it needs. It is a tribute to the world Smith foresaw that we have ended up with job titles like: Senior Packaging & Branding Designer, Intake and Triage Clinician, Research Centre Manager, Risk and Internal Audit Controller and Transport Policy Consultant – in other words, tiny cogs in a giant efficient machine, hugely richer, but full of private longings to give our multitudinous selves expression.

One of Adam Smith’s most intelligent and penetrating readers was the German economist Karl Marx. Marx agreed entirely with Smith’s analysis; specialisation had transformed the world and possessed a revolutionary power to enrich individuals and nations. But where he differed from Smith was in his assessment of how desirable this development might be. We would certainly make ourselves wealthier by specialising, but we would also – as he pointed out with passion – dull our lives and cauterise our talents. In describing his utopian Communist society, Marx placed enormous emphasis on the idea of everyone having many different jobs. There were to be no specialists here. In a pointed dig at Smith, he wrote:

In communist society… nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes… thus it is possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, to fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner…without ever becoming a hunter, fisherman, shepherd or critic.

– Karl Marx, The German Ideology (1846)

It’s a beautiful but entirely unrealistic dream. We have collectively chosen to make work pay more rather than be more interesting. It’s a sombre thought but a consoling one too. Our suffering is painful but it has a curious dignity to it, because it does not uniquely affect us as individuals. It applies as much to the CEO as to the intern, to the artist as much as to the accountant. Everyone could have found so many versions of happiness that will elude them. In suffering in this way, we are participating in the common human lot. We can be sure that – whatever we do – parts of our potential will have to go undeveloped and die without ever having had the chance to come to full maturity – for the sake of the benefits of focus and specialisation.