Calm • Perspective

Everything Is So Weird

There are moments – terrifying but also useful, vertiginous, comedic and in their own way filled with grandeur and beauty – when we leave ordinary reality behind and perceive everything as for once entirely and profoundly weird.

We might have had a fever and have been lying in bed in our room staring at the ceiling for several days in a row. Or we might just have got off a very long flight in which we didn’t sleep all night and which left us with a strange metallic taste in our mouth and a discombobulated and bewildered mind. Or we might have had a doze in the sun and caught a little too many of its rays. We can call these disorientations if we like, they may involve illness and discomfort, but they also provide us with precious opportunities for recalibration.

Knocked off our customary moorings, we realise how much energy we normally devote to normalising the inherent strangeness of the universe. We manage – somehow – to walk through the world as if it made some sense. We do so-called serious things and succeed in not laughing in the course of sentence or stopping to sit on the pavement to hold our head in our hands. We read letters and gesticulate to explain motives and go to the bathroom as if any of this was somehow reasonable. We may pick up a fork and wonder for once with the correct level of enquiry: what on earth is this thing, with prongs that we impale bits of burnt biological existence on and put into a gap in our face filled with water and chew in order to live? What is a plug socket, a nose, a galaxy or a sound? We might look at ourselves in the mirror and ask why we have ears and eyes that apparently evolved from simpler cells in what we call – as if that were normal too – the Early Cambrian Period. We might linger and form our mouth into a circle and go Ooohhh and Eeyyyyy and Awww – and not pay attention to the ever more urgent knocks at the door enquiring as to our identity and wellbeing.

We used to do this a lot in childhood. What is a car, what is a button, why are there bees, what is mummy, what happens if I block my ears or say ‘w’ in rapid succession? Maybe those questions got answered too soon, too flatly, too normally by those looking after us, who also had to carry the shopping up the stairs and wash our hair (we understand). Maybe we need to go back to that stage and wonder all over again. What is a ‘border’? What is a towel? What is a word? What is the word word doing to convey that it means ‘word’?

We can quite quickly become rather hard to understand – which might be a nice change. We can put too much effort into sounding comprehensible. There is a legitimate space for nonsense in the correct order of things. Why are we here and not somewhere else? Why do we have a name? What if we insisted on being called something else? Why do we keep putting the front door key in this place? Why are we breathing now and not before and not after? What is a minute, what is ‘I’, what is lunch?

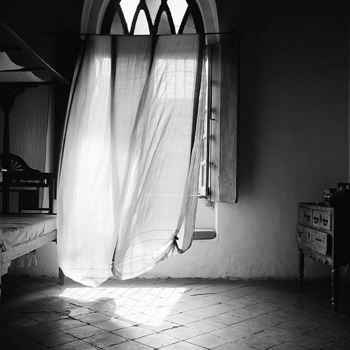

We can be grateful to photographers of genius and numinous sensitivity like Dayanita Singh and Robert Adam who know how to detect, and draw our attention, to the secret folds in the seams of what we insist on calling reality. As the curtain billows, as the afternoon light washes across the tiled floor, as the sound of water echoes in from the yard, we can stand immobile and wonder what what is, what a thought does, what a room means, what light illuminates.

Or, standing at the kitchen sink, with a mixture of despair and ecstasy, we can decide no longer to assume that we know what washing up liquid means, what a pan is, what is is.

Episodes of existential disorientation tend not to last very long. Phones ring. People come to the door. The fever abates. We have to resume the game. Soon we’re taking words and sentences and time and yawns entirely for granted again. We’re running within the sheltered alcoves of meaning we’ve carefully built up and police. Someone tells us that interest rates are set to rise or that it’s fish for dinner. And we agree, we might even come back with an opinion. Someone offers us a hand to shake and we shake it back in a complex geometry of palms and fingers. But we know now, deep down, that none of it is quite reasonable in the way it’s meant to be.

And once we know, really know, in an unfrightened way, life becomes a little less hidebound and heavy. A lot more can be funny. We don’t need, on top of everything else, to cleave so defensively to solemnity. We can have minor instances that allude back to the bigger existential miasma. We can wink at children under five (they know about weird); and animals (they know about weird too, especially cows or jack russells).

Life is fated to be far stranger, more beautiful and more fragile than we’ve ever allowed ourselves to know. We should do our best – whenever we can – to stop pretending too much of it ever makes sense.