Work • Meaning

Work and Maturity

One of the ideas that circulates below the surface of modern life is that work diminishes our personalities. We get paid in return for giving up a vital part of who we are. We look forward to holidays and retirement in order to nurture our true selves.

This analysis is a legacy of the Romantic movement. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, influential writers, artists and philosophers developed the view that the kind of work most people actually do – management, sales, manufacturing, logistics – is detrimental to the human spirit. The only exceptions to this analysis were a few jobs that were, and remain, not widely available in most societies: being a poet, novelist or artist.

Lord Byron: an influence on the assessment of modern logistics

The French Impressionist painter, Edgar Degas (who spent some time in the US), often painted the deeply unheroic characteristics of the trading world. His brokers and speculators are presented as people who have a limited outlook. They are dull, uninspiring figures. They confirm our worst fears about how we might end up, after years in trade.

Edgar Degas, Bureau du coton à la Nouvelle-Orléans, 1873

It’s only when we are off work that we can begin to be the interesting, real version of who we are.

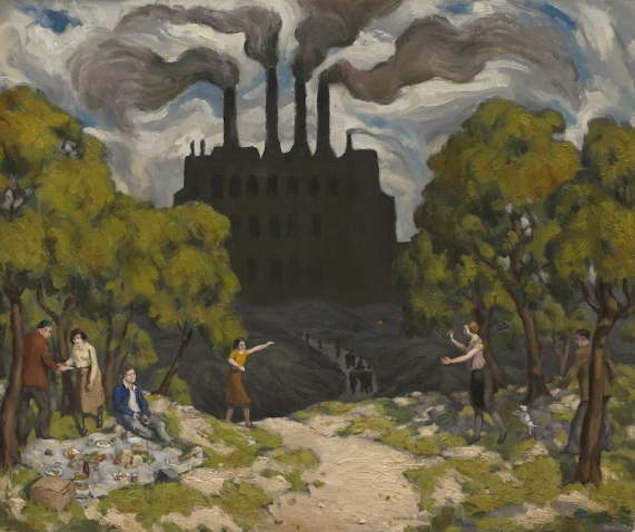

Dark Satanic Mills, Cyril Mann, 1925

In the 1840s, Henri Daumier won great success portraying lawyers as arrogant, greedy and dishonest.

They may not have started out that way – they may have been eager reformers and crusaders for justice. But it was a profession (like most others) designed, Daumier thought, to crush anyone’s better nature.

Our culture has taken to heart this sad Romantic notion of work. Sometimes it is more than deserved. But there is an important alternative view, which starts by being alive to some of the drawbacks of the Romantic idealisation of ‘home’. Of course there can be some pleasant times over the kitchen table on the weekend, but life outside of work is often full of challenges, humiliations and displays of the very worst kinds of behaviour. Home can be where we’re short of skills; a place of difficulty. One longs for Monday morning, for sanity to return.

He goes to the office to calm down; she finds it easier to run her business than manage her marriage

Our labour is not merely something we unfortunately have to do; it is ideally part of our development. Work is a place where we can learn the skills – and ultimately the maturity – that we might otherwise be very short of in the rest of our lives. Via the experience of work we might develop some crucial abilities:

How to Learn

Most workplaces are devoted to the idea of the progression and development of employees. They know how much easier it is to work with who they have, rather than constantly part ways with people. The fact that someone doesn’t yet know how to make an excellent presentation or how to manage an IT team isn’t seen as terminal. They can learn. They can do a course; get some practice; find a mentor, be assessed to check they’re making good enough progress. They can sit down with someone and determine what didn’t go so well and focus on what needs to be improved. Work has an idea of development inherent within it.

By contrast, the domestic sphere is opposed to learning. We’re meant to know it all already: how to be a good friend, lover and parent. Except we generally have no clue – and never make much progress.

How to express truths without causing upset

Business life constantly gives us lessons in the art of how to tell someone a tricky bit of information without them panicking or being horrified. Home life finds us far less tactful.

In need of classes on feedback

We say nothing and fester or are brutal and give the blunt version of the hard facts. There are tears and slammed doors.

Clever businesses know they need to be experts in the arts of good communication. They can only function well because tricky news reaches the people who need to know it without destroying their esteem. So negative facts are not regarded in a personal light; there’s a protocol of giving plenty of support before firing the arrow, and there are traditions in which being open to criticism is seen as a major mark of character.

How to listen to strange views

Romantic love is based on the notion of perfect agreement. One gets together with people because they see the world as one does. It’s a beautiful ideal – until there are conflicts, at which point the entire edifice of a relationship may be called into question. If we loved one another, would we ever disagree or see things differently?

Rembrandt: The Cloth Merchant’s Syndicate, 1662

Work isn’t like this. These people (painted by Rembrandt in the 17th century) were the members of a ratings agency: grading the quality of bales of cloth, so that merchants could trade with confidence. This was central to Dutch trade. Each of the six individuals around the table has a very distinct personality, and would have come at many issues from quite alternative perspectives and yet they are united by the task at hand. They seem to bring their better selves to work: one imagines them as good at solving disagreements; they would have listened to each other with respect (‘I see your point; however, I wonder if perhaps …).

How to be patient with fiddly things

Almost all work is fiddly. It requires patience, it demands that we slow ourselves down and master hurdles. The cloth cutter has had to put aside a lot of his natural wildness and impulsiveness in order to make his living. To learn the trade means not just to acquire a means to earn money; it’s a coded lesson in growing up.

Contrary to the Romantic view, it might be that we are quite often simply the better version of ourselves at work. We’re more dignified and more patient, more tolerant and more loveable. Furthermore, we are developing skills that – tantalisingly – are needed and can be used elsewhere, especially in the bedroom and kitchen. Rather than leaving work in order to relax, it might be that we need to come to work in order to be a better person and lover.

As yet we’re not quite fully focused on this potential and so don’t see how big a contribution work could be making to our private lives. Being a good employee shouldn’t be that different from being that truly important thing, a good person.

If we were sketching the utopia, we’d not be looking for a society in which people didn’t have to work. It would be one in which many more people had the chance to acquire via their work the skills which would be useful to them across the whole of their lives.