Self-Knowledge • Emotional Skills

Cultural Consolation

1. Introduction

Our societies frequently proclaim their enormous esteem for culture and the arts. Music, film, literature, painting, photography and sculpture enjoy superlative prestige and are viewed by many as close to the meaning of life.

But our societies also have a strict sense of what properly appreciating the arts should involve. Sensible homage is associated with acquiring technical knowledge, with taking advanced qualifications in the humanities, with knowing historical details and with respecting, at least in substantial part, the canon as it is now defined.

Strangely, what we are not generally encouraged to do – and indeed what we might be actively dissuaded from attempting – is to connect up works of culture with the intimate agonies and aspirations of our own lives. It is quickly deemed vulgar, even repugnant, to seek personal solace, encouragement, enlightenment or hope from high culture. We are not, especially if we are serious, meant to view cultural encounters as opportunities for didactic instruction in how to live and die well.

In Leaving the Atocha Station, a novel by Ben Lerner, an American PhD student, used to considering art as material for academic analyses and scholarly seminars, visits Madrid’s Prado museum. In one of the quieter rooms, he spots a fellow visitor who moves slowly and looks intently at a range of key works, including Roger van der Weyden’s Descent from the Cross, Paolo de San Leocadio’s Christ the Saviour and Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights.

What might it be right to do in front of this?

Rogier Van der Weyden, Descent from the Cross

What astonishes the graduate student and eventually the guards of the museum is that in front of each of these masterpieces, the visitor doesn’t merely politely look at the caption or the guidebook; he doesn’t just note the fine brushstroke and the azure of the skies. He bursts into tears and cries openly at the sorrow and beauty on display, at the contrast between the difficulties of his own life and the spirit of dignity and nobility of the works on the wall. Such an outburst of intense emotion is deeply unusual in a museum (museums may routinely be referred to as our secular cathedrals, but they aren’t – as cathedrals once were – intended to be places to reveal one’s grief and gratitude). Listening to the man’s sobs, the guards at the Prado grow understandably confused and nervous. As the author puts it, they cannot decide:

whether he was the kind of man who would damage a painting, spit on it, tear it from the wall or scratch it with a key – or if he was having a profound experience of art… What is a museum guard to do…? On the one hand, you are a member of a security force charged with protecting priceless materials from the crazed… on the other hand…if your position has any prestige it derives precisely from the belief that [great art] could legitimately move a man to tears… Should the guards ask the man to step into the hall and attempt to ascertain his mental state… or should they risk letting this potential lunatic loose among the treasures of their culture?

The dilemma points with dry humour to the paradox of our contemporary engagement with culture: on the one hand, we insist on culture’s importance. On the other, we limit what we are meant to do with culture to a relatively polite, restrained and principally academic relationship, at points frowning on those who might treat it more viscerally and emotionally, as if it might be a sophisticated branch of a notorious category: self-help.

This resistance, however well-meaning, nevertheless misses that the great works of culture were almost invariably created to redeem, console and save the souls of their audiences. They were made, in one way or another, with the idea of changing lives. It is a particular quirk of modern aesthetics to sideline or ignore this powerful underlying ambition, to the point where to shed tears in front of a painting of the death of the son of God may put one at risk of ejection from a national museum.

Yet the power of culture arguably best emerges not when we conceive of it as an object of critical study or historical curiosity, but when we rely on it as a therapeutic tool which can be put to use in a quest to grow somewhat less isolated, frightened, shamed, restricted or skittish. Rather than focus on what a work of art might tell us about the time and place it was made or about the person who created it, we should develop the confidence to connect up cultural masterpieces with our own dilemmas and pains, using them as a resource with which to address a range of our most debilitating and pernicious agonies.

2. Companionship

The greatest share of the art that humans have ever made for one another has had one thing in common: it has dealt, in one form or another, with sorrow. Unhappy love, poverty, discrimination, anxiety, sexual humiliation, rivalry, regret, shame, isolation and longing; these have been the chief constituents of art down the ages.

Yet, although suffering is endemic to our species, we are, in public discussion, often unhelpfully coy about the extent of our grief. The chat tends to be upbeat or glib; we are under awesome pressure to keep smiling in order not to shock, provide ammunition for enemies or sap the energy of the vulnerable.

We thereby end up not only sad, but sad that we are sad – without much public confirmation of the essential normality of our melancholy. We grow harmfully stoic or convinced of the desperate uniqueness of our fate.

All this culture can correct, standing as a record of the tears of humanity, lending legitimacy to despair and replaying our miseries back to us with dignity, shorn of many of their haphazard or trivial particulars. ‘A book [though the same could be said of any art form] must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us,’ proposed Kafka, in other words, a tool that can help release us from our numbness and provide for catharsis in areas where we have for too long been wrong-headedly brave.

There is relief from our submerged sorrows to be found in all of history’s great pessimists. For example, in the words of Seneca: ‘What need is there to weep over parts of life? The whole of it calls for tears.’ Or the sigh of Pascal: ‘Man’s greatness comes from knowing he is wretched’. Or the ironic maxims of Schopenhauer: ‘There is only one inborn error, and that is the notion that we exist in order to be happy… The wise know it would have been better never to have been born.’

Such pessimism tempers prevailing sentimentality. It provides an acknowledgement that we are inherently flawed creatures: incapable of lasting happiness, beset by troubling sexual desires, obsessed by status, vulnerable to appalling accidents and always – slowly – dying.

Richard Serra, Fernando Pessoa (2007-08)

Richard Serra’s gigantic steel sculpture, Fernando Pessoa knows all about sadness. Unlike modern society, it does not glibly suggest that we cheer up; it insists that sorrow is written into the contract of life. The overtly monumental character of the work constitutes a declaration of the normality of darkness. Just as Nelson’s column in the centre of Trafalgar Square is confident that we will admit the importance of naval heroism, so Fernando Pessoa (named after a Portuguese poet who knew so much about suffering: ‘Oh salty sea, how much of your salt / is tears from Portugal’) is confident that we will recognise and respond to the legitimate place of the most solemn emotions at the core of existence. Rather than needing to be alone with such moods, the work – in part through its sheer scale – proclaims them as central and universal features of life.

Importantly, Serra’s work presents sorrow in a dignified way. It does not go into details. It does not analyse any particular cause of suffering (your humiliation at work, your loss in love). It presents sadness to us in general as a grand and ubiquitous emotion. Frustrated hope and grief may have particular local causes, but they are ultimately irrevocable features of every life. Nothing is so sure as that we will fail and regret. We can see Serra’s work, like so many cultural productions, as ‘sublimated’ sorrow, whereby base and perhaps unimpressive local experiences are converted into something universal and noble, providing us with a serious vantage point from which to survey the difficulties of our condition.

Serra’s work does not refer directly to our relationships or to the stresses and tribulations of our day-to-day lives. Its function is to give us access to a state of mind in which we are acutely conscious of sadness from a detached position. The work is sombre, rather than sad; calm, but not despairing. And in that condition of mind – that state of soul, to put it more romantically – we are left, as so often with works of art, better equipped to deal with with the intense, intractable and particular griefs that lie before us.

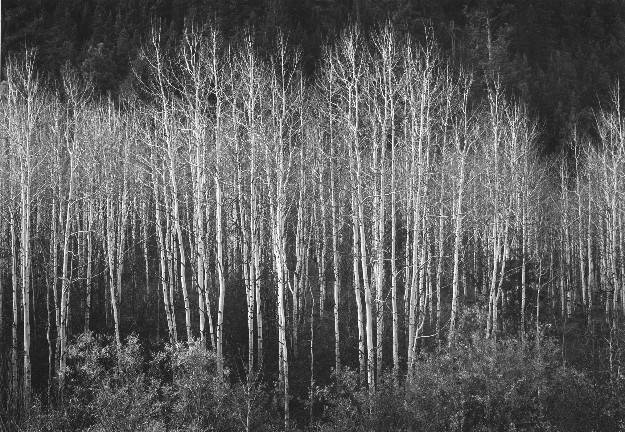

Contemplating our own mortality in the falling leaves

Ansel Adams, Aspens, Dawn, Autumn, Dolores River Canyon, Colorado, 1937

A similar move can be interpreted in Ansel Adams’s magisterial photograph of some aspen trees in the autumn in Colorado. They are shedding their leaves, another year is drawing to a close, the smell of decay is in the air. The image is not directly ‘about’ anything, and yet it creates a context in which feelings of loss and decline can be contemplated without panic or a sense of persecution. The image offers us an impersonal composed sublime view of some of the horrifying truths of human life: that everything is doomed to disintegration, that we will all face our own autumns, that everything must end and that the people we love and we ourselves will die. But the horror behind such facts is presented within the setting of the grandeur of nature. We too are part of biological necessity and share the fate of all living things. Adams’s image doesn’t try to remove our fears, it nobly tries to steady us in the face of them.

This is a move we encounter repeatedly in the arts: other people have had the same sorrows and troubles that we have; it isn’t that they don’t matter or that we shouldn’t have them or that they aren’t worth bothering about. What counts is how we perceive them. We encounter the spirit or voice of someone who profoundly sympathises with suffering, but allows us to sense that through it, we’re connecting with something universal and unashamed. We are not robbed of our dignity, we are discovering the deepest truths about being human – and therefore we are not only degraded by sorrow but also, strangely, elevated.

We can feel this especially in the presence of sad music. One of the most calming things that societies have ever devised is the lullaby. In almost every culture there has ever been, mothers have rocked and sung their babies to sleep. A humbling point that a lullaby reveals is that it’s not necessarily the words of a song that make us feel more tranquil. The baby doesn’t understand what’s being said but the sound has its effect all the same. The baby is showing us that we are all tonal creatures long before we are creatures of understanding. As adults, we grasp the significance of words of course, but there remains a sensory level which cuts through and affects far more than an argument or an idea ever could. The musician can, at points, trump anything the philosopher might tell us.

Ancient Greek mythology was fascinated by the story of the famous musician Orpheus. At one point he had to rescue his wife from the underworld. To get there he needed to make his way past Cerberus the ferocious three-headed dog who guarded the entrance to the land of the dead. Orpheus was said to have played such sweet, enchanting music that the wild beast calmed down and became – for a while – mild and docile. The Greeks were giving themselves a reminder of the psychological power of music. Orpheus didn’t reason with Cerberus, he didn’t try to explain how important it was that he should be allowed to pass, he didn’t speak about how much he loved his wife and how much he wanted her back. Cerberus was – as we ourselves are at times of distress – pretty much immune to reason. But he was still open to influence. It was a matter of finding the right channel to reach him.

When we feel anxious or upset, kindly people sometimes try to comfort us by pointing to facts and ideas: they try to influence our thinking and – via careful arguments – to quieten our distress. But, as with Cerberus, the most effective way to deal with sorrow may simply be to play us music.

For instance, in Schubert’s Ave Maria (composed in 1825) one feels enfolded in a generous, tender embrace, one will encounter no criticism or rebuke but endless depths of understanding and compassion for one’s troubles. The music lifts us up and gently distracts us from the immediate cause of agitation (as a parent might try to distract an upset child). Peter Gabriel’s Don’t Give Up is designed as a similar kind of musical therapy. It’s intended to be taken at points where we feel like giving up, when we’ve lost all confidence and feel crushed by the demands of the world. The strategy is to be as sympathetic as an imagined mother: first to acknowledge the horribly painful sense of failure and then to offer a kindly reassurance. The message is not that one’s plans will inevitably work out, but that one’s human worth is not on the line if they don’t. The music offers us what at such points we can’t offer ourselves: compassion and faith.

In the 1730s, J. S. Bach produced his Mass in B minor, perhaps the greatest musical axe ever to be brought to bear on the frozen sea inside us. Near the beginning there is the Kyrie: a call to the congregation to recognise the ways they’ve hurt and wronged others, and a plea that God will forgive their unkindness. A five-voice fugue theme (alto, soprano I, soprano II, bass) and a step-wise ascending melody, interrupted by a lower sighing motive, encourage us to feel repentance about our own failings while hinting at the eventual certainty of redemption.

Not only are we sad, we are also, most of us, lonely with what saddens us. We can imagine ourselves as a series of concentric circles. On the outside lie all the more obvious things about us: what we do for a living, our age, education tastes in food and broad social background. We can usually find plenty of people who recognise us at this level. But deeper in are the circles that contain our more intimate selves, involving feelings about parents, secret fears, day dreams, ambitions that might never be realised, the stranger recesses of our sexual imagination and all that what we find beautiful and moving.

Though we may long to share the inner circles, too often we seem able only to hover with others around the outer ones, returning home from yet another social gathering with the most sincere parts of us aching for recognition and companionship. Traditionally, religion provided an ideal explanation for, and solution to, this painful loneliness. The human soul – religious people would say – is made by God and so only God can know its deepest secrets. We are never truly alone, because God is always with us. In their touching way, religions were onto an important problem: they recognised the powerful need to be intimately known and appreciated and admitted frankly that this need could not realistically ever be met by other people.

What replaced religion in our imaginations has been the cult of human-to-human love we now know as Romanticism, which bequeathed to us a beautiful, reckless idea that loneliness might be capable of being vanquished, if we were fortunate and determined enough to meet the one exalted being known as our soul mate, someone who could understand everything deep and strange about us, who would see us completely and be enchanted by our totality. But the legacy of Romanticism has been an epidemic of loneliness, as we are repeatedly brought up against the truth: the radical inability of any one other person to wholly grasp who we truly are.

Yet there remains, besides the promises of love and religion, one other – and more solid – resource with which to address our loneliness: culture.

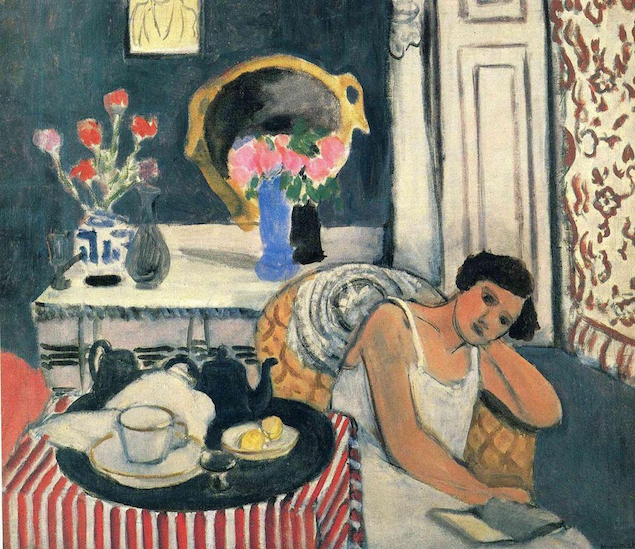

Henri Matisse, Woman Reading, 1984

Henri Matisse began painting people reading from his early 20s and continued to do so throughout his life; at least thirty of his canvases tackle the theme. What gives these images their poignancy is that we recognise them as records of loneliness that has been at least in part redeemed through culture. The figures may be on their own, their gaze often distant and melancholy, but they have to hand perhaps the best possible replacement when the immediate community has let us down: books.

The English psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott – working in the middle years of the 20th century – was fascinated by how certain children cope with the absences of their parents. He identified the use of what he called ‘transitional objects’ to keep the memory of parental love strong even when the parents weren’t there. So a teddy bear or a blanket, he realised, could be a mechanism for activating the memory of being cared for, a mechanism that is usefully mobile and portable and is always accessible when the parents are at bay.

Winnicott proposed that works of art can, for adults, function as more sophisticated versions of just these kinds of transitional objects. What we are at heart looking for in friendship is not necessarily someone we can touch and see in front of us, it is a person who shares, and can help us develop, our sensibility and our values, someone to whom we can turn and look for a sign that they too feel what we have felt, that they are attracted, amused and repulsed by similar things. And strangely, it appears that certain imaginary friends drawn from culture can end up feeling more real and in that sense more present to us than any of our real-life acquaintances, even if they have been dead a few centuries and lived on another continent. We can feel honoured to count them as among our best friends.

Christen Kobke lived in and around Copenhagen in the first half of the 19th century – he died of pneumonia in his late thirties in 1848 – but we might consider him as among our closest friends because of his sensitivity to just the sort of everyday beauty that we may be deeply fond of, but that gets very little mention in the social circles around us. From a great distance, Kobke acts like an ideal companion who gently works his way into the quiet, hidden parts of us and helps them grow in strength and self-awareness.

The arts provide a miraculous mechanism whereby a stranger can do the things we properly identify as lying at the core of friendship. And when we find these art-friends, we are unpicking the experience of loneliness. We’re finding intimacy at a distance. The arts allow us to become the soulmates of people who – despite having been born in 1630 or 1808 – are in limited, but crucial ways, our proper companions. The friendship may even be deeper than that we could have enjoyed in person, for it is spared all the normal compromises that attend social interactions. Our cultural friends can’t converse fully of course and we can’t reply (except in our imagination). And yet, they travel into the same psychological space, at least in some key respects, as we are in at our most vulnerable and intimate points. They may not know of our latest technology, they have no idea of our families or jobs, and yet, in areas that really matter to us, they understand us to a degree that is at once a little shocking and deeply thrilling.

Confronted by the many failings of our real life communities, culture gives us the option of assembling a tribe for ourselves, drawing their members across the widest ranges of time and space, blending some living friends, with some dead authors, architects, musicians and composers, painters and poets.

The fifteenth-century Italian painter Verrocchio – one of whose apprentices was Leonardo da Vinci – was deeply attracted to the biblical story of Tobias and the Angel. It tells of a young man, Tobias who has to go on a long and dangerous journey. But he has two companions: one a little dog, another an angel who comes to walk by his side, advise him, encourage him and guard him.

The old religious idea was that we are never fully alone; there are always special beings around whose aid we can call on. Verrocchio’s picture is touching not because it shows a real solution we can in fact count on, but because it points to the kind of companionship we would love to have and yet normally don’t feel we can find.

Yet, there is an available version. Not, of course, in the form of winged creatures with golden halos round their heads. But, rather, the imaginary friends that we can call on from the arts. You might feel physically isolated in the car, hanging around at the airport, going into a difficult meeting, having supper alone yet again or going through a tricky phase in a relationship – but you are not psychologically alone; key figures from your imaginary tribe (the modern version of angels and saints) are with you: their perspective, their habits of mind, their ways of looking at things are in your mind, just as if they were really by your side whispering in your ear. And so we can confront the difficult stretches of existence not simply on the basis of our own small resources but accompanied by the accumulated wisdom of the kindest, most intelligent voices of all ages gone by.

Given the enormous role of sadness in our lives, it is one of the greatest emotional skills to know how to arrange around us those cultural works that can best help to turn our panic or sense of persecution into consolation and nurture.

3. Hope

Much to the consternation of sophisticated people, a great deal of popular enthusiasm is directed at works of culture that are distinctly cheerful: songs about hope, films about couples that work through their problems and in the visual arts, cheerful, pleasant scenes: meadows in spring, the shade of trees on hot summer days, pastoral landscapes, and smiling children. The highest selling postcard of art in France turns out to be a reproduction of Poppies by Claude Monet.

Claude Monet, Poppies, 1873

Sophisticated people tend to scorn. They are afraid that such enthusiasms might be evidence of a failure to acknowledge or understand the awful dimensions of the world. But there is another way to interpret this taste: that it doesn’t arise from an unfamiliarity with suffering, but from an all too close and pervasive involvement with it – from which we are impelled occasionally to seek relief if we are not to fall into despair and self-disgust. Far from naivety, it is precisely the background of suffering that lends an intensity and dignity to our engagement with hopeful cultural works.

Rarely are today’s problems created by people taking too sunny a view of things; it is because the troubles of the world are so continually brought to our attention that we stand in need of intelligent tools which can preserve our more hopeful dispositions.

What hope might look like

Henri Matisse, The Dance I, 1909

The dancers in Matisse’s Dance are not in denial of the troubles of this planet. But from within a normally imperfect and conflicted relationship with reality, one can look at their attitudes as an encouragement; they put one in touch with a blithe, carefree part of oneself which can help one cope with the inevitable rejections and humiliations. The picture should not be seen as sentimentally suggesting that all is well: and that, despite the evidence of experience, women always take delight in each other’s existence and bond together in mutually supportive networks. If the world were a kinder place than it is, perhaps we would be less impressed by, and in need of, hopeful works of art.

One of the strangest features of art is its power, occasionally, to move us to tears, not when we are presented with a harrowing or terrifying image, but when we see a work of particular grace and loveliness which feels, for a moment, heartbreaking. What is happening to us at these special times of intense responsiveness to beauty?

It’s normal to think that what makes people cry are sad things; that’s certainly the way it works when you’re a child. But the older one gets, the more one starts to notice an odd phenomenon: one starts crying not when things are horrible (one toughens up a little), but when they are suddenly and unexpectedly precisely the opposite, when they are unusually sweet, tender, joyful, innocent or kind. This, far more than grimness, is what can increasingly prompt tears.

We can notice this in films. In Richard Linklater’s film, Before Midnight, most of the action comprises a bitter series of arguments between a 40-something couple, played by Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke. They have been together for years, they are on holiday in Greece, and the film homes in on one day when the pair go and spend time alone in a smart hotel. They arrive in their room with the possibility of sex somewhere in both of their minds but instead, find themselves having a blazing argument. They rake up all the hurt from past years; they blame each other for every disappointment and swear at, and insult, one another with abandon.

“Find someone else to put up with your shit. You’re fucking awful to be with, you know”

f“I don’t love you anymore. I hate you, you’ve ruined my whole fucking life”

Eventually, the wife storms out, leaving her room key and her husband behind. It feels agonisingly real. But, after a few hours of sulking, Hawke goes out in search of Delpy and finds her alone in a nearby restaurant terrace. They are both a little sheepish around each other, as one often is after a row, and he sits down opposite her with poignant formality.

In a beautiful closing sequence, they start to talk with unusual honesty. It’s difficult, but we can see that, despite everything (kids, too many sacrifices, exhaustion, not enough sex, perhaps a one-night stand or two) they do still love and desire one another very much. Their rage is an explosion of the frustration inherent within all long-term relationships. They get so deeply upset because they know that, day-to-day, they need so much from one another and they don’t always get it. They’re not magically going to stop bickering in the future. But this moment of kindness and sympathy, playfulness and gentleness, after such a bruising confrontation, comes as a huge relief and is deeply tender to behold. Their admission of shared love is moving because it reminds us at once of the struggles in our own lives and of what at heart we really want: reconciliation, forgiveness, tenderness, an end to the fighting, a chance to say sorry… We start to cry at a brief vision of a state of grace from which we’re exiled most of the time.

“I’m sorry. We both are. You drive me crazy, but I love you like I always did”

Take another example from another medium and from further back in history: a small ivory statuette of the Virgin and Child – it is just 41 cm high – in the Louvre in Paris, dating from about 1250.

The most striking feature is the mother’s face: one of welcome and joy; the kind of look we hope to receive when someone is unreservedly glad to see us. Mary’s charm and kindness may give rise to poignant emotions. We feel this is how life should be, this is what love looks like and what we should be giving to one another. But at the same time, we know it’s not easy; we’re pained by an acute sense that our lives are not usually like this. We may ache for all the lost innocence of the world (and of our own lives). Loveliness and goodness in art (at the Louvre, in a children’s book, or on a screen) can make the actual ugliness of existence all the more vivid. And that’s precisely why we cry at this poignant reminder of an elusive paradise.

The more difficult our lives, the less it might take to make us cry; even a flower might start to move us. The tears – if they come – are in response not to how sad the flower is, but at how its prettiness exists within such a very pitiless and mean world. The French nineteenth-century artist Henri Fantin-Latour painted a sequence of flowers. He was, as his self portrait suggests, intensely aware of the tragedy of existence, he wasn’t focusing on flowers out of misplaced innocence, his acquaintance with grief made him all the more alive to its occasional opposite.

We appreciate beauty more when we are aware of life’s troubles

(left) Henri Fantin-Latour: Self-portrait (1861); (right) Henri Fantin-Latour: Roses (1871)

Consider the difference between a child playing with an adult and an adult playing with a child. The adult’s delight is more intense because of a sense of how fragile such episodes of innocent contentment really are. The child’s joy is naive, and such joy is a lovely thing. But the the adult’s joy is placed within a recollection of the tribulations of existence – which is what makes it poignant. That’s what makes us ‘moved’, and sometimes cry. It must therefore be an unfair loss if we condemn all art that is gracious and sweet as ‘sentimental’ and in denial. In fact, such work can only impact us because we already know what reality is typically like. The pleasure of pretty art draws upon dissatisfaction. If we did not find life difficult, beauty would not have the appeal it does; were we to consider the project of creating a robot which could love beauty we should have to do something apparently rather cruel: we would have to ensure that it was able to hate itself, to feel confused and frustrated, to suffer and hope that it didn’t have to suffer; for it is against this kind of background that beautiful art becomes important to us, rather than merely nice.

For many of us, instead of being complacent (and hence needing to confront awkward truths) we’re liable to have the reverse problem: we’re so aware of what’s wrong that we’re despondent and paralysed. The Beatles’ warm, supportive Hey Jude – with its key line: ‘don’t be afraid’ – sees the reasons for potential despair as obvious: we get withdrawn and lonely, we give up, our problems feel too big. Its optimism isn’t denying this. It sees hope and cheerfulness as important ingredients in facing difficult situations. Similarly, one of Mozart’s most beautiful songs – Sleep Softly from Zaide – captures a beautiful moment of love: you see your partner sleeping and you feel incredibly tender towards them. It’s not a denial that couples often squabble, disappoint and frustrate one another. It’s not pretending that this is how we always feel. Rather it’s taking a rare, and very lovely, experience and preserving (or bottling) it, so that we can strategically reconnect with it when things have grown dark. It is because we are so aware of how hard relationships can be that we need an artificial way of reminding ourselves of the very positive and kindly feelings we also really do have towards our partners – but which tend to get lost amongst the normal conflicts and stand-offs of being in couple.

We’re leaky creatures – hope drains away, not because the situation is genuinely hopeless but because we are so attuned to seeing what’s wrong. It’s precisely because we so readily lose hope that the optimistic reminders, hope in amber, provided by culture are so important to us.

4. Balance

Few of us are entirely well ‘balanced’. Our psychological histories, relationships and working routines mean that many of our emotions incline a little too much in one direction or another. We may, for example, have a tendency to be too complacent – or else too insecure, too trusting or else too suspicious, too serious or else too lighthearted, too calm or too excited.

The particular imbalances we suffer from may be specific to us, but the phenomenon of being unbalanced is general – and, surprisingly, it is an issue that culture is particularly placed to help us with, for works can put us powerfully in touch with concentrated doses of our missing dispositions, and thereby restore a measure of equilibrium to our listing inner selves.

It is an emotional skill to be ready to sense an inner imbalance and then to take the steps necessary to rectify it with the help of culture. We might register that we are suffering from a mood of longing and disenchantment with what strike us as our rather humdrum and ordinary lives. The realisation isn’t complex in itself; what counts is the confidence to see that culture might have a solution to our mood – as well as the imagination to seek it out. We might find our way to a film about an ordinary school teacher who we, the audience, realise is delightful even though they lack any of the external markers of status. Through the film, we may be taught how to see the very real dignity and grace of ordinary life – and can recognise that a little of this, fairly, belongs to us as well.

In another mood, we may recognise that it might be a different sort of film we need. We often go so far down the track of teaching ourselves about the importance of gentleness and compromise, sometimes we unwittingly develop a problem around self-assertion and resistance to the demands of others. We might have learned too well to suppress our own appetite for a fight, our own desire for victory. Yet in a world where conflict is unavoidable, good people sometimes need to strengthen their willingness to face down opposition – not always to compromise and play it safe, but to take risks instead, to get out and fight, to relish victory and to be a bit more ruthless in the service of noble and deeply important ends. Sometimes it is not enough to be right, you also need to win.

So some of us might well benefit from seeing films that tell tales of heroism: that follow someone who has to navigate the world, kill a dragon, outwit some baddies, penetrate a corrupt organisation… The film shouldn’t ideally leave us just in awe at the daring of another. It should do that far more valuable thing: educate us by example so that we too become just a little more heroic and brave where we need to be.

The notion that art has a crucial role in rebalancing us emotionally promises to answer the vexed question of why people differ so much in their aesthetic tastes. Why are some people drawn to minimalist architecture and others to the Baroque? Why are some people excited by bare concrete walls and others by floral patterns? Why do some like quiet films about relationships and others war epics? Our tastes will depend on what spectrum of our emotional make-up lies in shadow and is hence in need of stimulation and emphasis. Every work of art is imbued with a particular psychological and moral atmosphere: serene or restless, courageous or careful, modest or confident, masculine or feminine, bourgeois or aristocratic – and our preferences for one kind over another reflects our varied psychological gaps. We hunger for artworks that will compensate for our inner fragilities and help to return us to a viable mean.

Imagine that we have fallen into a way of life that suffers from too much intensity, stimulation and distraction. Work is frantic across three continents. The inbox is clogged with 200 messages every hour. There is hardly time to reflect on anything once the day starts. It explains why we might be powerfully drawn to a minimalist interior, where things appear calm, logical and reduced to their essence. This is our true home, from which our way of life has exiled us.

Beauty to balance out over-stimulation

Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House, 1951

But because we are not all missing the same things, the kinds of art that have a capacity to rebalance us, and therefore arouse enthusiasm in us, will differ markedly. Imagine we happen to be a bureaucrat in one of the sleepier branches of the Norwegian civil service based in the idyllic though rather quiet town of Trondheim near the Arctic circle. Our days run like clockwork. We are always home by 5.15 pm and do the crossword before bed. The last thing we may be attracted to is a pristinely ordered home by Mies van der Rohe. We might be drawn instead to Flamenco music, the paintings of Frida Kahlo and the architecture of Mexico’s Catedral de Santa Prisca – varieties of art to restore life to our slumbering souls.

An art to rebalance an over-quiet soul

Façade of the Catedral de Santa Prisca y San Sebastian, Taxco, Mexico

Whole nations can manifest longings for balance and will use art to help them achieve it. After too much aristocratic decadence, many in late 18th-century France felt the need to get back in touch with marshal solemnity and spartan simplicity and so found refuge in the pared-down works of Jacques-Louis David.

Art to rebalance oneself after too many mistresses, too much gold and too many decadent parties

Jacques-Louis David, The Oath of the Horatii, 1784

By the later part of the 19th century in England, the materialism, scientific obsession and capitalist rationality of the age drove many to long for more faithful, mystical days, and so to locate ‘beauty’ in the images inspired by the literature and history of the Middle Ages.

Art to rebalance oneself after too many railways, factories and readings of Darwin

Edmund Leighton, Tristan and Isolde, 1902

What we call ‘beautiful’ is any work of art that supplies a missing dose of a much-needed psychological component, and we dismiss as ‘ugly’ one which forces on us moods or motifs that we feel threatened or already overwhelmed by. Our contact with art holds out the promise of inner wholeness.

5. Compassion

Our fear of failure would not be so great were it not for an awareness of how often failure tends to be harshly viewed and interpreted by others. We fear not just poverty, we’re terrified of mockery and ridicule.

So unforgiving is the tone in which the majority of ruined lives is discussed that if the protagonists of many works of art – Oedipus, Antigone, Lear, Othello, Emma Bovary, Anna Karenina, Hedda Gabler or Tess – had had their destinies chewed over by a cabal of colleagues or old school acquaintances, they would have been unlikely to emerge well from the process. They might have fared even less well if the media had come across them. We can imagine the headlines:

Othello: LOVE-CRAZED IMMIGRANT KILLS SENATOR’S DAUGHTER

Madame Bovary: SHOPAHOLIC ADULTERESS SWALLOWS ARSENIC AFTER CREDIT FRAUD

Oedipus the King: SEX WITH MUM WAS BLINDING!

If there is something incongruous about these headlines, it is because we are used to thinking of the subjects they refer to as inherently complex, and naturally deserving of a solemn and respectful attitude rather than the prurient and damning one which newspapers rarely hesitate to accord to their victims. But, in truth, there is nothing about these subjects to make them inevitable objects of concern and respect. That the legendary failed characters of art seem noble to us has little to do with their qualities per se and almost everything to do with the way we have been taught to consider them by their creators and chroniclers.

There is one art form in particular which has, since its inception, dedicated itself to recounting stories of great failure without recourse to mockery or judgement. While not absolving people of responsibility for their actions, its achievement has been to offer to those involved in catastrophes – disgraced statesmen, murderers, the bankrupt, emotional compulsives – a level of sympathy owed, but rarely paid, to every human.

Tragic art began in the theatres of ancient Greece in the sixth century BC and followed a hero, usually a high-born one, a king or a famous warrior, from prosperity and acclaim to ruin and shame, through some error of his own. The way the story was told was likely to leave members of an audience at once hesitant to condemn the hero for what had befallen him and humbled by a recognition of how easily they too might one day be ruined if ever they were presented with a situation similar to that with which the hero had been faced. The tragedy would leave them sorrowful before the difficulties of leading a good life and modest before those who had failed at the undertaking.

If the newspaper, with its language of perverts and weirdoes, failures and losers, lies at one end of the spectrum of understanding, then it is tragedy that lies at the other – embodying an attempt to build bridges between the guilty and the apparently blameless, challenging our ordinary conceptions of responsibility, standing as the most psychologically sophisticated, most respectful account of how a human being may be dishonoured, without at the same time forfeiting the right to be heard.

In his Poetics (c. 350 BC), Aristotle attempted to define the central constituents of an effective tragedy. There needed to be one central character, he said, the action had to unfold in a relatively compressed space of time and, unsurprisingly, ‘the change in the hero’s fortunes’ had to be ‘not from misery to happiness’ but on the contrary ‘from happiness to misery’.

But there were two other, more telling requirements. A tragic hero had to be someone who was neither especially good nor especially bad, an everyday, ordinary kind of human being at the ethical level, someone we could relate to with ease, a person who combined a range of good qualities with certain defects, perhaps excessive pride or anger or impulsiveness. This character would then make a spectacular mistake, not from any profoundly evil motive, but from what Aristotle termed in Greek a hamartia or lapse of judgement, a temporary blindness, or a factual or emotional slip. And from this would flow the most terrible peripeteia or reversal of fortune, in the course of which the hero would lose everything he held dear and almost certainly pay with his life.

Pity for the hero, and fear for oneself, based on an identification with him, would be the natural emotional outcome of following such a tale. The tragic work would educate us to acquire modesty about our capacity to avoid disaster and at the same time guide us to feel sympathy for those who had met with it. We were to leave the theatre disinclined ever again to adopt an easy, superior tone towards the fallen and the failed.

Aristotle’s insight is that the sympathy we feel for the fiascos of others almost always has its origins in a palpable sense of how easily we too might, under certain circumstances, be involved in a calamity like theirs; just as our sympathy diminishes in proportion to the degree in which their actions come to seem as if they lie outside the range of our possibilities. How would a sane, normal person do that, we may feel upon hearing of characters who have married rashly, slept with members of their own families, murdered their lovers in jealous frenzies, lied to employers, stolen money or allowed an avaricious streak to ruin their careers. Confident of a cast-iron wall separating our nature and situation from theirs, comfortable in the well-worn saddle of our high horse, our capacity for tolerance is replaced by coldness and derision.

But the tragedian draws us close to an almost unbearable truth: that every folly or blindness of which a human being has been guilty in the course of history can be traced back to aspects of our own nature; that we bear within ourselves the whole of the human condition, in its worst and best aspects, so that we too might be capable of anything under the right, or rather the very wrong, circumstances. Once an audience has been brought close to this fact, they may willingly dismount from their high horses and feel their powers of sympathy and humility enhanced; they may accept how easily their own lives could be shattered if certain of their more regrettable character traits, which had until then led them to no serious accident, were one day to come into contact with a situation that allowed these flaws an unlimited and catastrophic reign.

In the summer of 1848, a terse item appeared in many newspapers across northern France. A twenty-seven-year-old woman named Delphine Delamare, née Couturier, living in the small town of Ry not far from Rouen, had become dissatisfied with the routines of married life, had run up huge debts on superfluous clothes and household goods, had begun an affair and, under emotional and financial pressure, had taken her own life by swallowing arsenic. Madame Delamare left behind a young daughter and a distraught husband, Eugène Delamare, who had studied medicine in Rouen before taking up his post as a health officer in Ry, where he was loved by his clients and respected by the community.

One of those reading the newspaper was a twenty-seven-year-old aspiring novelist, Gustave Flaubert. The story of Madame Delamare stayed with him, it became something of an obsession, it followed him on a journey around Egypt and Palestine until, in September 1851, he settled down to work on Madame Bovary, published in Paris six years later. One of the many things that happened when Madame Delamare, the adulteress from Ry, turned into Madame Bovary, the adulteress from Yonville, was that her life ceased to bear the dimensions of a black-and-white morality tale. As a newspaper story, the case of Delphine Delamare had been seized upon by provincial conservative commentators as an example of the decline of respect for marriage among the young, of the increasing commercialization of society and of the loss of religious values. But to Flaubert, art was the very antithesis of crass moralism. It was a realm in which human motives and behaviour could for once be explored in a depth that made a mockery of any attempt to construe saints or sinners.

Readers of Flaubert’s novel could observe Emma’s naïve ideas of love, but also where these had come from: they followed her into her childhood, they read over her shoulder at her convent, they sat with her and her father during long summer afternoons in Tostes, in a kitchen where the sound of pigs and chickens drifted in from the yard. They watched her and Charles falling into an ill-matched marriage. They saw how Charles had been seduced by his loneliness and by a young woman’s physical charms, and how Emma had been impelled by her desire to escape a cloistered life and by her lack of experience of men outside third-rate romantic literature. Readers could sympathize with Charles’s complaints against Emma and Emma’s complaints against Charles. Flaubert seemed almost deliberately to enjoy unsettling readers’ desire to find comfortable answers. No sooner had he presented Emma in a positive light than he would undercut her with an ironic remark. But then, as readers were losing patience with her, as they felt her to be nothing more than a selfish hedonist, he would draw them back to her, would tell them something about her sensitivity that would make them cry. By the time Emma had lost her status in her community, had crammed arsenic into her mouth and laid down in her bedroom to await her death, few readers would be in a mood to judge.

We end Flaubert’s novel with fear and sadness at how we have been made to live before we can begin to know how, at how limited our understanding of ourselves and others is, at how great and catastrophic are the consequences of our actions, and at how pitiless and uncompromising the upstanding members of the community can be in response to our errors.

However, the true lessons of Flaubert’s novel should go far beyond the book itself. The great tragedies should matter to us not because of the specific stories they narrate, but because of the way in which they are narrated. It is the voice that counts, one of sympathy, complexity, gentleness and lack of easy judgement – in a sense, the voice of love.

The point of being exposed to it repeatedly is so that ultimately, it becomes the voice we can start to tell our own story in. We too are inept, flawed, messy creatures heading – at some point – for a fall. So it matters immensely that lodged in our minds we have a voice that isn’t just the punitive one of the public square, but is one that can make some of the same moves as we witness in Sophocles, Shakespeare or Flaubert. It isn’t a case of writing up our lives as they would have done. It’s seeing that, in our failures, we deserve no less sympathy than the unfortunate victims of the world’s greatest tragedies. A world in which people properly imbibed the lessons implicit within tragic art would be one in which the consequences of failure would cease to weigh upon us so heavily, a world in which we had learnt how properly to extend a loving perspective upon ourselves and our fellow wretched humans.

6. Knowledge

One of the more frustrating, yet fundamental, things about being human is that we can’t understand ourselves very well. One side of the mind frequently has no clear picture of what the other happens to be upset about, anxious around or looking forward to. We make a lot of mistakes due to a pervasive self-ignorance.

Here too culture can help, because in many cases, it knows us better than we know ourselves and can provide us with an account, more accurate than any we might have been capable of, of what is likely to be going on in our minds.

Marcel Proust wrote a long novel about some aristocratic and high bourgeois characters living in early 20th-century France. But towards the end of his novel, he made a remarkable claim. His novel wasn’t really about these distinctly remote-sounding people, it was about someone closer to home, you:

“In reality, every reader is, while he is reading, the reader of his own self. The writer’s work is merely a kind of optical instrument which he offers to the reader to enable him to discern what, without this book, he would perhaps never have experienced in himself. And the recognition by the reader in his own self of what the book says is the proof of its veracity.”

In the great works of culture, we have an overwhelming impression of coming across orphaned bits of ourselves, evoked with rare crispness and tenacity. We might wonder how on earth the author could have known certain deeply personal things about us, ideas that normally fracture in our clumsy fingers, but that are here perfectly preserved and illuminated. Take, for example, the self-knowledge offered by one Proust’s favourite writers, the 17th-century philosopher, Le Duc de La Rochefoucauld, the author of a slim volume of aphorisms known as the Maxims:

‘We all have strength enough to bear the misfortunes of others.’

It’s an idea closely followed by the equally penetrating:

‘There are some people who would never have fallen in love, if they had not heard there was such a thing.’

And the no less accomplished:

‘To say that one never flirts is in itself a form of flirtation.’

We are likely to smile in immediate recognition. We have been here ourselves. We just never knew how to condense our mental mulch into something this elegant.

When Proust compares literature to ‘a kind of optical instrument’, what he means is that it is a high-tech machine that helps us to focus on what is really unfolding in ourselves and others around us. Great authors turn vagueness into clarity. For example, once we have read Proust, and are then abandoned by a lover who has kindly digressed on their need to spend ‘a little more time on their own’, we will benefit from seeing the dynamic clearly captured, thanks to Proust’s line: ‘When two people part, it is the one who is not in love who makes the tender speeches.’ The clarity won’t make the lover return; but it will do the next best thing, help us to feel less confused by, and alone with, the misery of having been left.

The more writers we read, the better our understanding of our own minds stands to be. Every great writer can be hailed as an explorer – no less extraordinary than a Magellan or Cook – into new, hitherto mysterious corners of the self. Some explorers discover continents, others spend their lives perfectly mapping one or two small islands, or just a single river valley or cove. All deserve to be feted for correcting the ignorance in which we otherwise meander through our internal world. The Japanese poet Matsuo Basho clarifies our feelings of loneliness; Tolstoy explains our ambition to us, Kafka makes us conscious of our dread of authority, Camus guides us to our alienated and numb selves and under Philip Roth’s guidance, we become conscious of what happens to our sexuality in the shadow of mortality.

The 20th-century English writer Virginia Woolf did not enjoy good health. In an essay titled On Being Ill, she lamented how little we tend to grasp clearly what illness really feels like. We casually say we’re not well, or have a headache, but we lack a focused vocabulary for our ailments. There is one large reason for this: because of how little illness has been written about by talented authors. As Woolf remarks: ‘English, which can express the thoughts of Hamlet and the tragedy of Lear, has no words for the shiver and the headache. The merest schoolgirl, when she falls in love, has Shakespeare or Keats to speak her mind for her; but let a sufferer try to describe a pain in his head to a doctor and language at once runs dry.’ This turned out to be one of Woolf’s great tasks as a literary explorer. She brought into focus what it’s like to be tired, close to tears, too weak to open a drawer, irritated by a pressure in one’s ears or beset by strange tremors near one’s chest. Woolf became the Columbus of illness.

An effect of reading a book which has devoted attention to noticing faint yet vital tremors, is that, once we’ve put the volume down and resumed our own lives, we can attend to precisely the things which the author would have responded to had he or she been in our company. With our new optical instrument, we’re ready to pick up and see clearly all kinds of new objects floating through consciousness. Our attention will be drawn to the shades of the sky, to the changeability of a face, to the hypocrisy of a friend, or to a submerged sadness about a situation which we had previously not even known we could feel sad about. A book will have sensitised us, stimulated our dormant antennae by evidence of its own developed sensitivity. Which is why Proust proposed, in words he would modestly never have extended to his own novel, that:

‘If we read the new masterpiece of a man of genius, we are delighted to find in it those reflections of ours that we despised, joys and sorrows which we had repressed, a whole world of feeling we had scorned, and whose value the book in which we discover them suddenly teaches us.’

These lines connect up with an equally prescient quote from Ralph Waldo Emerson:

‘In the minds of geniuses, we find – again – our own neglected thoughts.’

It isn’t just ourselves we learn about through culture. It is, also, of course, the minds of strangers, especially those we would not – in the ordinary run of things – have ever learnt much about. With our optical instruments in hand, we get to learn about family life in Trinidad, about being a teenager in Iran, about school in Syria, love in Moldova and guilt in Korea. We get taken past the guards right into the King’s bedroom (we hear him whispering to his mistress or doubting his attendants) and the pauper’s hovel, the upper middle class family’s holiday villa and the lower middle-class family’s caravan.

Thanks to all this, we have a rare opportunity to spare ourselves time and error. Literature speeds up the years, it can take us a through a whole life in an afternoon, and so lets us study the long-term consequences of decisions that – in our own cases – normally work themselves out with dangerous slowness. We have a chance to see in accelerated form what can happen when you worry only about art and not so much about money, or only about ambition and not so much about your own children; what happens when you despise ordinary people or are disturbingly concerned with what others think. Literature helps us avert mistakes. All those heroes who commit suicide, those unfortunate demented souls who murder their way out of trouble or the victims who die of loneliness in unfurnished rooms are able to teach us things. Literature is the very best reality simulator we have, a machine which, like its flight equivalent, allows us safely to experience the most appalling scenarios that it might, in reality, have taken many years and great danger to go through, in the hope that we’ll be ever so slightly less inclined to misunderstand ourselves, swerve blindly into danger or succumb before time.

7. Encouragement

In England in the 1880s, a group of art lovers, most of them young, forward-looking and metropolitan, began a movement known as Aestheticism. Their core belief was that in a rapidly secularising world, art and culture could provide us with a new moral framework; they could, as religion had once done, guide, inspire and console us. In particular, they could play a vital role in encouraging us to be good, because beautiful objects and environments were not, in their eyes, merely meaninglessly pretty. They were goads to virtue. The Aestheticists believed – as the Ancient Greeks had done – that beauty was synonymous with goodness while ugliness was an incarnation of evil.

This turned badly designed objects and environments from unfortunate eyesores to political priorities; they weren’t just ugly, they might make us bad. Cities, houses, chairs, plates and teapots needed to be attractively made, in order to generate the right sort of atmosphere around which good lives could unfold.

Blue and white teaware with hand-painted Prunus blossom characteristic of the aesthetic movement, George Jones & Sons Ltd, 1880s

The Aestheticists were easy to mock. Many of them had a somewhat earnest and precious air. The satirical magazine Punch took regular aim at them. In one cartoon, an ardent young couple examine a teapot they have received as a wedding gift. ‘It is quite consummate, is it not!’ exclaims the bridegroom. ‘It is indeed!’ replies his bride, ‘Oh Algernon, let us live up to it!’

George Du Maurier, ‘The Six-Mark Tea-pot’ Punch, (October 30, 1880)

The idea of ‘living up to’ a teapot sounds daft, but it contains a not-at-all inane background thesis: that the quality of designed environments matters because we are hugely vulnerable to the suggestions emanating from them about how we might behave and more broadly who we might be. In degraded, battered, run-down streets or around ugly tea pots, it is easier for hope to escape and for the less admirable sides of our nature to come to the fore, whereas around finely made teapots and dignified thoroughfares, our better selves are granted a chance to flourish.

This idea would not have sounded in any way strange to the Zen Buddhist philosophers behind the Japanese tea-ceremony. These theorists paid acute attention to the design of teacups and teapots, and wanted them to function as visual reminders of prized Zen qualities of character like modesty and forbearance. Minor blemishes were deliberately allowed to remain on cups, so as to enforce a message that imperfection is an inevitability to which we should graciously accommodate ourselves. The glaze was unevenly applied and the overall shape often a little wonky, nudging us towards a serene negotiation with our own flaws. The cups, exquisite yet very human, amounted to small moments of wisdom embodied in ceramic objects.

Philosophy in a teacup: White koro glazed tea bowl in Ido style, Japan, 16th century

What can hold true for a teacup is all the more apparent at the level of architecture. In 1956, the Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer was invited to play a central role in the creation of his country’s new capital city. Among the most impressive of the buildings he designed for Brazilia was the National Congress, sculpted into an elegant futuristic saucer-like shape.

An encouragement for Brazil

National Congress, Brasilia, Oscar Niemeyer (designed 1956)

Brazil is a country of frenetic economic activity, of rainforest and Amazonian villages, favelas, soccer obsessions, scandals, beaches and intense disagreement about political priorities … none of which is apparent from contemplation of the National Congress. Instead the building encourages us to imagine the Brazil of the future; it is a glass and reinforced concrete ideal for the country to develop towards. In the future, so the building argues, Brazil will be a place where rationality is powerful; where order and harmony reign; where elegance and serenity are normal. Calm, thoughtful people will labour carefully and think accurately about legislation; in offices in the towers, efficient secretaries will type up judicious briefing notes; the filing systems will be perfect – nothing will get lost, overlooked, neglected or mislaid; negotiations will take place in an atmosphere of impersonal wisdom. The country will be perfectly managed.

The building was an essay in flattery. It hinted that certain desirable qualities were already to some extent possessed by the country and by its governing class. We are used to thinking of flattery as bad – but it is deeply helpful, for flattery encourages us to live up to certain appealing images we should be led by. Children who are deeply praised for their first modest attempts at kindness are not being fooled, they are being helped to develop beyond what they actually happen to be right now. They are being given a loving chance to grow into the people they have flatteringly been described as already being.

Brazilia, like many a beautiful city, street, chair or teapot, matters because of its skill at encouraging the better sides of us. This is no idle or dispensable project. We are always on the verge of forgetting the lessons in goodness and fulfilment we know in theory and so lie at the mercy of messages sent out by our environment. We need to build lives and nations in which we are never far from works of art that can intelligently bring the best sides of us to the fore.

8. Appreciation

At the centre of our societies is a hugely inventive force dedicated to nudging us towards a heightened appreciation of certain aspects of the world. With enormous skill, it throws into relief the very best sides of particular places and objects. It uses wordsmiths and image-makers of near genius, who create deeply inspiring and beguiling associations – and it positions works close to our eyelines at most moments of the day. Advertising is the most compelling agent of mass appreciation the world has ever known.

Because advertising is so ubiquitous, it can be easy to forget that – of course – only a very few sorts of things ever get advertised. Almost nothing is in a position to afford the budgets required by an average campaign, something overwhelmingly reserved for those wealthy potentates of modern life: nappies, cereal bars, conditioners, hand sanitisers and family sedans.

This has a habit of skewing our priorities. One of our major flaws as animals, and a big contributor to our unhappiness, is that we are very bad at keeping in mind the real ingredients of fulfilment. We lose sight of the value of almost everything that is readily to hand, we’re deeply ungrateful towards anything that is free or doesn’t cost very much, we trust in the value of objects more than ideas or feelings, we are sluggish in remembering to love and to care – and are prone to racing through the years forgetting the wonder, fragility and beauty of existence.

It’s fortunate, therefore, that we have art. One way to conceive what artists do is to think that they are, in their own way, running advertising campaigns; not for anything expensive or usually even available for purchase, but for the many things that are at once of huge human importance and yet constantly in danger of being forgotten. In the early part of the twenty-first century, the English artist David Hockney ran a major advertising campaign for trees.

David Hockney, Three Trees Near Thixendale, Summer 2007

At the start of the sixteenth century, the German painter Albrecht Dürer launched a comparable campaign around the value of grass.

Albrecht Dürer, Great Piece of Turf, 1503

And in the 1830s, the Danish artist Christen Kobke did a lot of advertising for the sky, especially just before or after a rain shower.

Christen Kobke, Morning Light, 1836

In the psychological field, the French painter Pierre Bonnard carried out an exceptionally successful campaign for tenderness, turning out dozens of images of his partner, Marthe, viewed through lenses of sympathy, concern and understanding.

Pierre Bonnard, Woman with Dog, 1922

In an associated move, the American painter Mary Cassatt made a good case for the world-beating importance of spending some time with a child.

Mary Cassatt, Mother Playing with her Child, 1899

These were all acts of justice, not condescension. They were much-needed correctives to the way in which what we call ‘glamour’ is so often located in unhelpful places: in what is rare, remote, costly or youthful.

If advertising images carry a lot of the blame for instilling a sickness in our souls, the images of artists reconcile us with our realities and reawaken us to the genuine, but too-easily forgotten value, of our lives. Consider Chardin’s Woman Taking Tea. The sitter’s dress might be a bit more elaborate than is normal today; but the painted table, teapot, chair, spoon and cup could all be picked up at a flea market. The room is studiously plain. And yet the picture is glamorous – it makes this ordinary occasion and the simple furnishings, seductive. It invites the beholder to go home and create their own live version. The glamour is not a false sheen that pretends something lovely is going on when it isn’t. Chardin recognises the worth of a modest moment and marshalls his genius to bring its qualities to our notice.

A modest moment, appreciated for its true worth

Jean-Simeon Chardin, Woman Taking Tea, 1735

It lies in the power of art to honour the elusive but real value of ordinary life. It may teach us to be more just towards ourselves as we endeavour to make the best of our circumstances: a job we do not always love, the imperfections of age, our frustrated ambitions and our attempts to stay loyal to irritable but loved families. Art can do the opposite of glamourise the unattainable; it can reawaken us to the genuine merit of life as we’re forced to lead it. It is advertising for the things we really need.

9. Perspective

Because of the way our minds work, it is very hard for us to be anything other than immensely preoccupied with what is immediately close to us in time and space. But in the process, we tend to exaggerate the importance of certain frustrations that do not, in the grander scheme, merit quite so much agitation and despair. We are inveterately poor at retaining perspective. Here too, culture can help – by carrying us out of present circumstances and reframing events against a more imposing or vast backdrop.

Some extremely worrying-sounding things are, always, happening in the world. We are surrounded by a media industry that knows it must scare us to survive and that the one thing (despite its overt commitment to free speech) it must always censor is the idea that on balance things will be OK. One place we can turn for relief is a resource that powerfully reminds us that extreme difficulties are never new, that the worst sounding troubles can be survived and that it has (extraordinarily) often been a lot worse even than this: an antidote that goes by the name of History.

When political events seem to have reached a new low, we might – for example – turn to the writings of the ancient Roman historian Suetonius. Born towards the end of the first century AD, Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus was an imperial administrator, chief secretary to the Emperor Hadrian and the first historian to try to give an accurate portrait of what the rulers of the Empire from Julius Caesar down to Domitian had actually been like. It’s a shocking story. Suetonius’s book amounts to a catalogue of extraordinary follies and crimes of the first twelve men to rule the western world. Amongst them, we find:

Julius Caesar: A thief, a liar, an egomaniac and a murderer.

Caligula: A notorious psychopath who, to quote Suetonius, ‘sent people down the mines or thrown to the wild beasts or confined in narrow cages where they they had to crouch or were sawn in half, not for major offences but because they did not properly admire a show he had sponsored at the Circus or did not refer with sufficient respect to his genius.’ We hear that: ‘The method of execution he preferred was to inflict numerous small wounds but avoiding all major organs. He often gave the command: ‘Make them feel they are dying.”

Nero: Of him we hear: ‘He dressed himself in the skins of wild animals and attacked the private parts of men and women bound to stakes.’ ‘He wandered through the streets at night randomly murdering strangers and throwing their bodies into the sewers.’

Vitellus: His ruling vices were gluttony and cruelty. He banqueted three or four times a day and he survived by taking frequent emetics. He used to give himself a treat by having prisoners executed before his eyes.’

Domitian: ‘At the beginning of his reign Domitian would spend hours alone every day catching flies and stabbing them with a needle-sharp pen.’

Though Suetonius writes about grotesque people – who were also at the time the most powerful people on the planet – he can leave one feeling remarkably serene. One might read him tucked up in bed, after news of the latest catastrophe. The experience is strangely reassuring, because it’s at heart a narrative of resilience.

Suetonius writes of earthquakes, plagues, wars, riots, rebellions, conspiracies, betrayals, coups, terrorism and mass slaughter. Considered on its own it might seem to be the record of a society whose collapse must surely be immanent. But, in fact, Suetonius was writing before – and not after – the most impressive period of Roman achievement – which would come fifty years later under the rule of the stoic philosopher and Emperor, Marcus Aurelius.

The disasters that Suetonius catalogues were compatible with a society heading overall towards peace and prosperity. Reading Suetonius suggests that it is not fatal for societies to be in trouble; it is in fact usual for things to go rather badly. In this respect, reading ancient history generates the opposite emotions to scanning today’s news. Events have been much worse before and things were, in the end, OK. People behaving very badly is a normal state of affairs. There have always been existential threats to the human race and civilisation. It makes no sense, and is a form of twisted narcissism, to imagine that our era has any kind of monopoly on idiocy and disaster. By reading Suetonius we enter unconsciously into his less agitated and more Stoic reactions. He and History more generally encourage access to what we need now more than ever: the less panicky, more resilient sides of ourselves.

In a very different medium, a similar move is being made by the Japanese photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto through his gigantic empty photographs of the Atlantic ocean in a variety of moods. What is most notable in these sublime scenes is that humanity is nowhere in the frame. We are afforded a glimpse of what the planet looked like before the first creatures emerged from the seas. Viewed against such an immemorial scene, the precise discontents in our relationship, the frustrations in our work, the machinations of our enemies matter ever so slightly less. We regain composure not by being made to feel more important, but by being reminded of the miniscule and momentary nature of everyone and everything.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, The Atlantic Ocean, 1989

As our eyes wander over the vast grey swell of the sea, we can immerse ourselves in an attitude of gratifying indifference to ourselves and everything about our laughably minor fate. The waters of time will close over us; and it will – thankfully – be as if we had never lived.

10. Conclusion

Works of culture can redeem us in a variety of ways – but we should never overlook that they can do so only on one condition: that they are successful as works of art. It isn’t enough that they should badly want to help us, that they should have powerful intentions to be companionable, serene or inspiring. They must also be these things in and of themselves. In other words, they cannot be mere manifestoes or declarations, they must – in addition – be good art.

That we need good art in the first place has to do with one of the deepest troubles of the human condition: that we are generally committed to rejecting or ignoring all good advice unless we have first been extremely skillfully charmed or seduced into accepting it. The point was memorably elaborated in the early 19th century by the German philosopher Hegel, who was deeply struck by the way in which good advice usually doesn’t cut through into our lives. Extremely wise ideas have, since the beginning of time, been offered to humanity. The argument for kindness rather than cruelty or the long-term over the short-term have been won long ago in the pages of serious philosophical texts. But, as Hegel was painfully conscious, this has never in itself had much impact on how we actually behave. What counts, he realised, isn’t simply the message, but also the medium.

And, he concluded, the very best medium for imparting ideas is good art. In his Lectures on Aesthetics (1826), Hegel suggested that the best art has the capacity to present important ideas in a seductive, captivating form. As he formulated it, ‘Art is the sensuous presentation of ideas.’ Sensuousness – beauty, lustre, charm, playfulness, wit – is no mere incidental add-on, it is what makes the difference between a message lodging in our minds and it flitting straight in and out again.

Hegel had particular admiration for the way the Ancient Greeks hadn’t restricted themselves to presenting their ideas as philosophy. They had managed to give them a more compelling form as theatre, they had set them to music and they had sculpted them out of stone. So for example, Apollo may have been the god of wisdom, but in order that his wisdom be remembered and adhered to, the Greeks had grasped that the god needed to be given a pleasing, even at points physically enticing outward form; that his hair had to be thick, his muscles akin to those of a great wrestler and his cloak teasingly drawn back. Only then would his wisdom emerge as properly believable.

Wisdom embodied in a sensuous form

Apollo Belvedere, ca. 120–140 CE

A great artist isn’t – therefore – just someone who sets out to help us to live and die well. It is someone who knows how to seduce us into wisdom, so that we are at once instructed, entertained, charmed and gripped.

We need culture around us because we are so poor at retaining our equilibrium and maturity. The best lessons are constantly draining from us. We must have the right songs, films, history books, plays and images to hand to keep us from succumbing to rage and error. Culture is our emotional apothecary, a storehouse of humanity’s finest bottled wisdom and compassion, with whose help we have the best chance of riding out our many inevitable moments of fragility and folly.