Self-Knowledge • Emotional Skills

Love-as-Generosity

Modern ideas of love are strongly associated with admiration. To fall in love with someone is typically assumed to involve an awe at a person’s physical and psychological virtues. We may speak of having fallen in love with particular wit or intelligence, bravery or beauty. We think of ourselves as in love when we reflect on a rare creature who seems in a myriad of ways stronger and more accomplished than we are; our love seems founded on admiration.

But there is another view of love that deserves to be explored if we are to improve upon our often marked inability to sustain long-term relationships – a philosophy of love that hinges upon a quality rarely mentioned in the context of couples, namely, generosity. In this view, to love someone means not just or primarily to experience admiration in the face of perfection, but a capacity to be uncommonly generous towards a fellow human especially at moments when they may be less than straightforwardly appealing. Love is here taken to be not a thrill in the face of accomplishment but a distinctive skill founded on the ability to see beyond a partner’s often off-putting outer dimensions, an energy to enter imaginatively into their experiences and bestow an ongoing degree of forgiveness and kindness in spite of trickiness and confusion. To love is, in this uncommon sense, above all else, to know how to be generous.

To consider love as generosity matters so much because, once we get to know someone well, we can almost be guaranteed to discover that their perfections are not as deep as we had initially assumed. If we equate love with admiration, greater acquaintance must always pre-empt a decline in love.

Unfortunately, the idea of love-as-generosity can sound so unfamiliar and in a way so arduous that we might instinctively recoil from the prospect of learning how to practise it. And yet it seems that almost all of us already know full well about this sort of love. It’s just we haven’t yet thought our knowledge relevant to relationships. This love is exactly and un-reflexively what we tend to display in the presence of small children – especially those who are between around two and four years old. Oddly, it turns out that we will have learnt a vital part of what it means to love when we have come to treat our adult lovers with some of the same forbearance and imagination as we treat the very young.

Small children sometimes behave in stunningly unfair and shocking ways: they scream at the person who is looking after them, angrily push away a bowl of animal pasta, throw away something one has just fetched for them. But we rarely feel personally agitated or wounded by their behaviour. And the reason is that we know not at once to assign a negative motive or mean intention to tricky phenomena. We reach around for the most benevolent interpretations we can pull together. We don’t immediately presume the child is proving maddening in order to upset us. We probably think that they are getting a bit tired, or their gums are sore or they are upset by the arrival of a younger sibling. We’ve got a large repertoire of alternative explanations ready in our heads to take the edge of unappealing traits – and none of these lead us to panic or get terribly agitated.

This is the reverse of what tends to happen around adults in general, and our lovers in particular. Here we imagine that others have deliberately got us in their sights. If the partner is late for our mother’s birthday because of ‘work’, we may assume it’s an excuse. If they promised to buy us some extra toothpaste but then ‘forgot’, we’ll imagine a deliberate slight. Their bad mood is a sign they are attempting to ruin our lives.

But if we employed the infant model of interpretation, our first assumptions would be quite different: maybe they didn’t sleep well last night and are too exhausted to think straight; maybe they’ve got a sore knee; maybe they are doing the equivalent of testing the boundaries of parental tolerance. Seen from such a point of view, the lover’s adult behaviour doesn’t magically become nice or acceptable. But the level of agitation is kept safely low. It’s very touching that we live in a world where we have learnt to be so kind to children: it would be even nicer if we learnt to be a little more generous towards the childlike parts of one another.

It sounds strange at first – and even condescending or despairing – to keep in mind that in crucial ways we always remain children. On the outside we’re obviously functioning adults. But to love with generosity is to recognise that parts of the psyche always remain tethered to the way they were at the early stages of life. This way of seeing the person one is with may be a helpful strategy for managing times when there are outbursts of deeply unreasonable petulance, sulkiness or flashes of aggression. When our partners fall far short of what we ideally expect from grown up behaviour and we dismissively label such attitudes as ‘childish’, without quite realising it, we are approaching a hugely constructive idea, but then (understandably though unfortunately) seeing it simply as an accusation – rather than what it truly is: a recognition of an ordinary feature of the human condition.

It is not an aberration or unique failing of one’s partner that they retain a childish dimension. It’s a normal, inevitable, feature of all adult existence. Adulthood simply isn’t a complete state; what we call childhood lasts (in a submerged but significant way) all our lives. Therefore, some of the moves we execute with relative ease around children must forever continue to be relevant when we’re dealing with another grown-up.

Our ability to continue to be loving, and to keep calm, around children is founded on the fact that we take it for granted that they are not able to explain what is really bothering them. We deduce the real cause of their sorrow from amidst the external symptoms of rage – because we grasp that little children have very limited abilities to diagnose and communicate their own problems.

Being benevolent to one’s partner’s inner child doesn’t mean infantilising them. This is no call to draw up a chart detailing when they are allowed screen time or to award stars for getting dressed on their own. It means being charitable in translating things they say in terms of their deeper meaning: ‘you’re a bastard’ might actually mean ‘I feel under siege at work and I’m trying to tell myself I’m stronger and more independent than I really feel’; or ‘you just don’t get it do you’ might mean ‘I’m terrified and frustrated and I don’t really know why, please be strong.’

We’d ideally also give more space for soothing rather than arguing; instead of taking our partner up for something annoying they’ve said we’d see them like an agitated child who is lashing out at that the person they most love because they can’t think of what else to do. We’d seek to reassure and show them that they are still OK, rather than (as is so tempting) hit back with equal force.

Of course, it’s much much harder to remain grown-up around another adult whose inner child is on display than it is being with an actual child. That’s because we can see that a child is a child. We adults have a far harder time than necessary because we are in the unfortunate position of looking like adults and therefore are always forgetting that we are not, despite the visual evidence, entirely grown-up within.

Naturally, the insight can’t all be one way. A capacity for benevolence to the inner child of a partner has to be linked to a recognition that we will have a similar need to be viewed in this benevolent way at other points. We can take it in turns. We can summon up the energy to be charitable to the inner three-year-old of the other – in part because we know that soon enough we are going to need them to do the same for us.

The accurate, corrective reimagining of the inner lives of others is a piece of empathetic reflection we constantly need to perform with ourselves and with others. We need to imagine the turmoil, disappointment, worry and sheer confusion in people who may outwardly appear merely aggressive. Our lover may be six foot one and holding down adult employment, but their behaviour may still sometimes be poignantly retrogressive. When they behave badly, what they don’t, but should perhaps say is: ‘Deep inside, I remain an infant, and right now I need you to be my parent. I need you correctly to guess what is truly ailing me, as people did when I was a baby, when my ideas of love were first formed’.

We are so alive to the idea that it’s patronising to be thought of as younger than we are; we forget that it is also, at times, the greatest privilege for someone to look beyond our adult self in order to engage with – and forgive – the disappointed, furious, inarticulate or wounded child within.

We have not always behaved as lovingly towards children as we tend to nowadays. Our modern attitudes are the result of deliberate efforts over a 150 years on the part of psychologists, writers and educators to lend prestige to a certain kind of love and entrench attitudes we today think of as normal. For most of history, humans had been regularly dismissive, indifferent and harsh towards children: they had imagined that being stern and demanding was the right approach. Fortunately, more than we generally accept, we love within a historical context and take our cue from what society tells us may be the right way to behave (‘There are some people who would never have fallen in love if they hadn’t heard there was such a thing,’ knew La Rochefoucauld). The profound shift in the idea of what adults should be like to children can be a source of inspiration for how we might learn to love differently in grown up contexts more generally.

At the heart of the idea of love-as-generosity is a capacity for imagination. Our personalities are often deceptive. We may be broken and in need of kindness, but our fragility and vulnerability is frequently hidden behind robust, assertive and angry outer characteristics. To know how to love is to make a mental leap outside of the available evidence; it is to imagine what cannot immediately be seen. We guess the other is anxious, not mean; is scared, not demented.

This mental leap is at the heart of the work of novelists and of what we can admire most in great works of fiction. The truly important novelists take us behind the scenes of human personality; they introduce us to some superficially appalling characters, but their genius is to unearth the humanity behind stock evil figures like the prostitute or the gambler, the alcoholic or the adulterer.

One of the best portrayals of love-as-generosity is to be found in Leo Tolstoy’s novel, Anna Karenina. The central character, Levin, has just got married to Kitty when he hears that his brother Nikolai has fallen very ill and lies close to death. Relations between the siblings has not been good for a long time. Nikolai is drunk, aggressive, a spendthrift and a dissolute wastrel. He lives in one squalid room having frittered his sizeable inheritance and behaves brutishly towards his long-time companion, a harassed, wretched young woman, a prostitute, called Masha. Levin is worried about what Kitty, a well-brought up, sheltered soul, will think – and hesitates to show his wife this side of his family. Yet they go to see the brother anyway and instead of being revolted by Nikolai, Kitty turns out to be deeply moved by his suffering. She refuses to be put off by the unprepossessing exterior. She cleans her brother-in-law, soothes him, feeds him and talks with him in a kind and patient way, making his sense of his feverish words. This, Tolstoy is telling us, is what real love is like. In Kitty’s eyes, Nikolai isn’t as he seems to be to others; a brutish failure of a man. He is a fundamentally well-meaning, thoughtful person who has been caught up in a string of misfortunes – as all of us in some ways are or will be.

Though we may not have reached such depths (yet), this is close to how we are all made to feel when someone loves us. It may be gratifying to be admired, but it is something much more profound and closer to the essence of love to be forgiven and understood in our less impressive moments, when we are unable to muster any of our virtues and cannot help but appear as wretched to the world. We know we will finally have tasted love when it is our vulnerability, fear, worry and sorrow that is what inspires a kindly response.

A significant consequence of this shift in focus from love-as-admiration to love-as-generosity is that the question of who we might get together with can grow a little less fraught. We have become notoriously tricky on this point, in part because of our technology. We hold out – often for longer than is wise – for what we call ‘the right person’, someone endowed with an exemplary range of virtues and accomplishments. We grow impatient with, and fire our existing partners in what we think of as a loving search for a greater degree of perfection.

But love-as-generosity doesn’t depend on so slender, vulnerable a base as does love-as-admiration. It accepts that what should be decisive in love is not the degree of perfection two people can bring to one another but the degree of imagination present in their assessment of each other’s frailties. Anyone we could get together with would, over time, require a considerable degree of generosity – for we are all deep trouble to be around from close up. Once we really understand love-as-generosity, we may come to accept that it almost doesn’t matter who we love. We could contemplate the odd-sounding, but ultimately wise and noble idea that we could love almost anyone, so good would we have become at isolating what is tender, pure and deserving of sympathy within even the most outwardly gnarled and damaged human heart.

*****

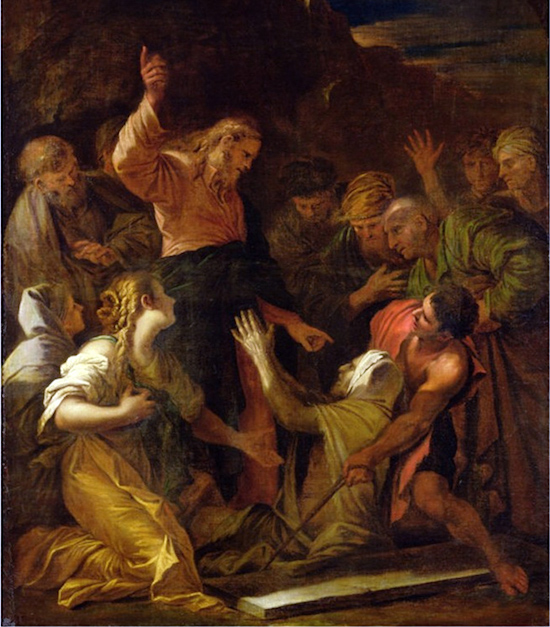

Irrespective of whether you consider Jesus a popular itinerant preacher or the Son of God, there’s a very odd thing about his views on love. He not only spoke a great deal about love: he went on to advocate that we love some highly surprising people.

At one point – described in chapter 7 of Luke’s Gospel – he goes to a dinner party and a local prostitute turns up – much to the disgust of the hosts. But Jesus is friendly and sweet and defends her against everyone else’s criticism. In a way that shocks the other guests, he insists that, at heart, she is a very good person.

There’s another story (in Matthew, chapter 8) where Jesus is approached by a man with leprosy. He’s in a disgusting state. But Jesus isn’t shocked, reaches out his hand and touches the man. Despite the horrendous appearance, here is someone (in Jesus’s eyes) entirely deserving of closeness and kindness. In a similar vein, at other times, Jesus conspicuously argues that tax collectors, thieves and adulterers are never to be thought of as outside the circle of love.

Many centuries after his death, the foremost medieval thinker Thomas Aquinas defined what Jesus was getting at in this way of talking about love: the person who truly understands love could love anyone. In other words: true love isn’t specific in its target; it doesn’t fixate on particular qualities, it is open to all of humanity, even (and in a way especially) its less appealing examples.

Today, this can sound like a deeply strange notion of what love is, for our background ideas about love tend to be closely tied to a dramatic experience: that of falling in love, that is, finding one, very specific person immensely attractive, exciting and free of any failings or drawbacks. Love is, we feel, a response to an overt perfection of another person.

Yet – via some admittedly extreme examples – a very important aspect of love is being pushed to the fore in Jesus’ vision. And we don’t have to be Christian – that is, we don’t have to believe there’s an afterlife or that Jesus was born to a virgin – to benefit from it.

At the heart of this kind of love is an effort to see beyond the outwardly unappealing surface of another human – in search of the tender, interesting, scared and vulnerable person inside.

What we know as the ‘work’ of love is the emotional, imaginative labour that’s required to peer behind an off-putting facade. Our minds tend fiercely to resist such a move. They follow well worn grooves that feel at once familiar and justified. For instance: if someone has hurt us we naturally see them as horrible. The thought they might themselves be hurting inside feels very weird. If a person looks odd, we find it extremely difficult to recognise there might well be many touching things about them deep down.

If unpleasant events happen in someone’s life – if they keep on losing their job or acquire a habit of drinking too much or even develop cancer – we’re somehow tempted to hold them responsible for their misfortunes.

It takes quite a deliberate, taxing effort of the mind to move ourselves off these deeply established responses. To do so might mean taking an unappealing-looking person and trying to imagine them as young a child, unselfconsciously playing on their bedroom floor. We might try to picture their mother, not long after their birth, holding them in her arms, overcome by passionate love for this new little life. Or perhaps, drunk and passed out, ignoring their desperate cries.

We might see a furious person in a restaurant violently complaining that the tomato sauce is on the wrong place on their plate – but rather than condemn and feel superior, we might try to construct a story of how this individual had come to be so impossible, and how powerless they must feel in a world where something (and not what they are ostensibly complaining about) has frustrated them to the core.

The more energy we expend in thinking like this, the more we stand to discover a very surprising truth: that we could potentially see the loveable sides of pretty much anyone.

That doesn’t mean we should give up all criteria when searching for a partner. It’s a way of saying that the nicest person will eventually require us to look at them with imagination as we try to negotiate around some of their gravely dispiriting sides.

And, of course, the traffic won’t ever be all one way. We too are deeply challenging to be around and therefore stand in need of a constantly imaginative, tender gaze to rescue us from being dismissed as merely another everyday monster – or leper.

*****

The so-called Mind-Body problem is one of the greatest and most quietly painful conundrums in philosophy – and more importantly, in everyday life.

The problem is rooted in the fact that in the eyes of other people, all of us are automatically and stubbornly associated with our bodies (which includes, of course, our faces). The way we look is the overwhelming factor that dictates how others assess our natures and our characters. Whatever lip service we might pay to less punitive ideologies, in the practical world, who ‘we’ are is taken to be how we look.

The sweet face is assumed to contain a gentle, benevolent owner; the large, red face with narrow eyes an angry and suspicious one. We trust that personal identity is indivisible from bodily form.

Yet there is one dramatic exception from this rule: our own cases. When it comes to us, we know – usually with considerable and ongoing sorrow – that the way we look is obviously not who we are. We are profoundly aware of a large gulf between our understanding of ourselves and the suggestions emitted by our faces. Inside we may feel tender, inspired, inquisitive, playful and young: but the face we see in the mirror is indelibly imprinted with an atmosphere that is stern, grave, humourless and ever more akin to that of an insipid elderly uncle. We may bravely try to push the hair this way and that, or soften the appearance with the help of a slightly brighter jumper or some intrepid shoes or dab some kind of cream or powder here and there – but nothing can ever overcome the monumental injustice to which we appear to be subject. It isn’t merely that we feel unattractive: we feel something bigger: misrepresented – as if we have been forced go into the world as an ambassador for a country we don’t actually inhabit or identify with.

The English essayist George Orwell once remarked that at 40, everyone has the face they deserve. This is as absurd and cruel as to suggest that everyone might have the illnesses, the income or the fate they deserve. No one, not even with 40 years of trying, has ever managed to change their facial appearance by an effort of the inner will so as better to reflect their identity. No one who has passionately thought of themselves as a button-nosed person over a half a lifetime has ever thereby shrunk their proboscis by even a quarter of a millimetre.

In fact, quite the opposite tends to happen: our characters are liable to mould themselves to the personalities implied by our faces, as a result of years of other people assuming that this must be who we are, and treating us in the light of our appearance. The gentler sides of someone who looks gentle will thereby constantly be invited to the surface by the expectations and encouragement of others. The person who is routinely assumed to be a bit sly because of the slope of their eyelids may end up fitting with the prevailing story of who they are.

The mind-body problem leads us to understand some of what love, in its most generous, imaginative guises, should really involve: a commitment to remember that the other is not how they appear; that their body was imposed and not chosen and that there may be a very different character trapped within their physical envelope.

The writer Cyril Connolly, who struggled with his weight all his life, and felt sickened by his round full cheeks, bald head and what he termed ‘accountant’s expression’, once wrote: ‘Inside every fat man is a thin one trying to get out…’

But the phenomenon should not be limited to the fat-thin dichotomy. Inside a distressing number of us, there is someone else trying to get out, perhaps a mellow 65-year-old man from the body of a 25-year-old woman, or a thoughtful nerdy girl from the body of a middle-aged irritable male.

The best we can do to overcome the mind-body problem is not to fiddle with our clothes, invest in hairdressers or endanger our health with plastic surgery. We will never be able properly to align mind and body by outward sculpting. The solution is to recognise that the problem is an existential part of being human and therefore to strive always to remember, in spite of all the visual evidence, and in a spirit of love, that the bodies of others are very separate from the character of their minds – in the hope that others will gift us a comparably generous and kind interpretation when their gaze turns to our own faces and bodies.