Work • Meaning

How Could a Working Life Be Meaningful?

For most of history, work was not a topic of sustained reflection because it seemed at once so simple, so inevitable and so unpleasant. It was overwhelmingly focused on the provision of basic food and shelter and offered next to no stimulation or spiritual reward. At best one could describe it as a backbreaking and desperate curse.

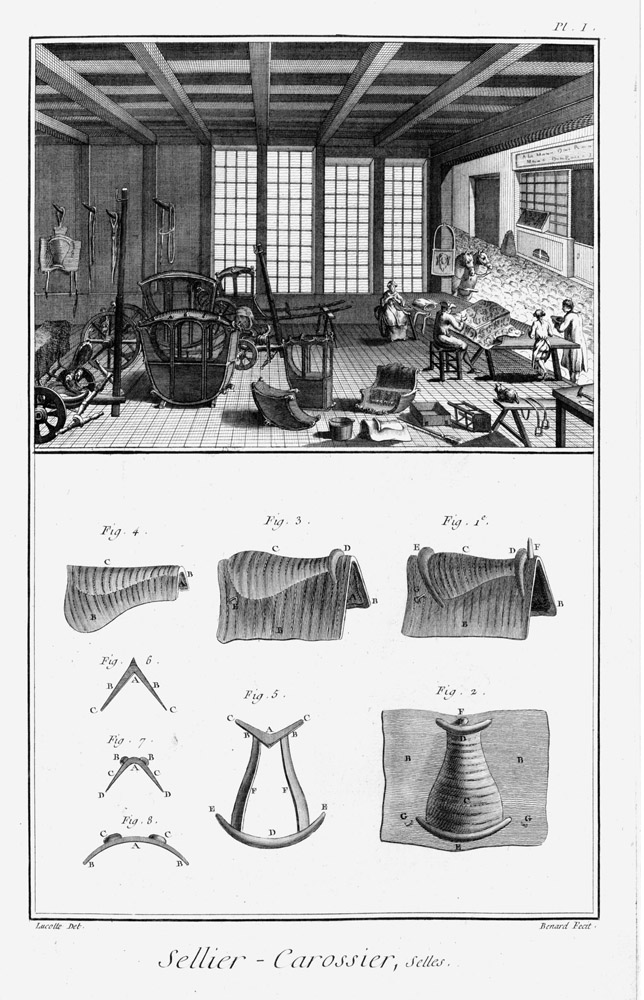

The modern age begins with hope. By the eighteenth century, work had diversified, certain trades were growing more prosperous, others less exhausting. Humans began to step back and ask themselves questions: how was work organised, what was it for and what might be its future? There was a new self-consciousness and inquisitiveness. The French Encyclopédie, which set out to condense all human knowledge and was published in 32 volumes between 1751 and 1772, devoted a third of its entries to work. With the help of elegant forensic illustrations, it described hundreds of occupations at unusual depth. There were substantial entries on pipe-organ making, turning and lathe work, baking and sugar refining, paper-making and bookbinding, tanning and soapmaking, mining and metallurgy, porcelain and pottery manufacture.

There was a grateful, childlike fascination to the entries. Humanity was waking up to how beautifully specific and skilled its labours could be. There were people in workshops who understood exactly how to manipulate the forty different kinds of tools required to make a saddle; a relatively everyday object like a bed emerged as a piece of intricate engineering demanding admirable degrees of training and experience. The production process of Gruyère cheese was more interesting than most novels.

Two hundred years later, in a comparable spirit of investigation, the American photographer Bill Owens travelled around Southern California, photographing an eclectic range of people at their work, then married up their portraits with their reflections on their activities. The tone was less heroic – much of the work we do remains minor, bathetic and disconnected from higher ambitions – but it conveyed an equal fascination with the devotion and sacrifice our labours demand.

“I got tired of selling waterbeds so I opened a beanbag store. Waterbeds were just a fad.”

“At Dirty Sally night Club I earn $80 a night on tips. Everyone is here to have a good time at the disco, drink and pick each other up. The outfit is just a part of the job. It helps me get better tips and I am careful not to get too familiar with the customers.”

‘As a theoretical physicist I generally don’t tell people what I do. It’s useless explaining because, unless you know about the subject, it’s mysticism. Some of my mathematical problems take a year or more to solve. I carry them around with me. So really I’m working all the time, even when I’m in bed.’

‘Being a salesman is easy. It’s fun to manipulate people, to get a reaction, to find out where they’re at. I used to be in management; I hated it. All I want to do is sell furniture.’

We understand so much more about who we are at work, but we still grapple with questions of what work is, and what it might properly aim at. We are still in search of a philosophy of work. We might begin like this: what we call ‘work’ are all the efforts we make to compensate for what nature doesn’t automatically or easily provide us with. We work in order to reduce particular sorts of pain and increase particular sorts of pleasure that nature did not, on its own, take care of. The history of work is the record of all the systematic techniques and processes we had to devise to make life more bearable than it would otherwise have been: nature didn’t provide sufficient food on trees and in bushes and so we started to plant seeds; nature left us shivering in our natural state and so we began sewing. Every time humans encountered a failing in nature, they tried to invent a tool; every tool is an instrument to extend our command over an indifferent environment in the service our needs. When we hear the word tool, certain sorts of objects tend to come to mind: we couldn’t carry sufficient quantities of water in our cupped hands, and we devised the bucket; we couldn’t deliver enough force in our fists to smash a stone and we invented the hammer…

Paleolithic Handaxe, Lake Natron, Tanzania, British Museum

But if we define a tool as anything we devise because nature hasn’t granted us a power to act in a particular way on the world, far more things are tools than the simple mechanical objects we tend to associate with the term: a book is a tool to correct our inability to hold a great number of our ideas in memory; a painting is a tool to preserve an impression of the beauty of the night sky or the underside of clouds at dusk; a holiday is a tool to organise a succession of satisfactions relating to a foreign climate or culture; a religion is a tool to foreground certain ideas of morality and consolation that might otherwise disappear from our vacillating minds. ‘Civilisation’ is the summary of everything we have ever devised to counteract the harshness and discomforts of our natural condition.

The centuries show humans learning to invent an ever more complicated range of tools – to address ever more subtle and complicated needs. We have moved from devising tools for simple aspects of survival to tools that address our aspirations to flourish. Along the way, we made a striking discovery: that coming up with and operating certain tools might at points be very pleasurable. This was a surprise. For most of our time on earth, work had been no fun at all: it had been repetitive, physically arduous and mentally unstimulating – which is why the aristocratic assumption had always been that, once money allowed, one would down tools at once and devote oneself to leisure. No rich person would ever think of continuing to work in order to address the needs of others. But at the dawn of the modern world, humanity became conscious of forms of work that, even while they generated money through being useful to others, also stimulated and rewarded those who undertook them. One might please oneself and one’s audience.

Satisfying work begins with an insight into happiness. What later gets called an enterprise, a profession or a trade is – at the outset – just an idea about increasing pleasure or decreasing pain. We start the long journey towards work when we spot something that we would like others to enjoy – or a friction or discomfort we would want to remove from their lives. For example, we notice how interesting it tastes when a sandwich is made with a particular variety of oil and lemon. Or we see how stimulating the very old and the very young find it to spend time together and wonder how they could do so more regularly. Or we spot that there is a height above the knee where a hem hangs that is especially beguiling. An insight into happiness could begin when we think of combining two earlier disconnected attempts to please: perhaps a delicate high voice can be married up with a deep bass set within a piece of music the length of a choral mass. Maybe the way they handle wool in Norway can be twinned with the way they treat metal in northern Italy. Or we can be challenged to deepen a sort of happiness that is already present but in a relatively undeveloped form. Perhaps a comedian’s routine could be taken to a new level if it could also expound some leading ideas from science. Or we are struck by an impediment to happiness that irks us especially: why do we need to spend so much time filling out of forms, why can’t the system automatically reorder a part, couldn’t we arrange it so that the machine would leave no residue?

The unattended pleasure we identify might be very personal and apparently little known. It can require courage to imagine that it could ever matter to other people, that our secret satisfactions and frustrations might have direct equivalents inside strangers. Successful work requires taking an intelligent guess about the lives of the audience. ‘In the minds of geniuses,’ wrote Emerson, ‘we find our own neglected thoughts.’ And one could add, in perceptive businesses, we find our own neglected pleasures and pains addressed. They know us better than we knew ourselves, what we call profit being the reward for understanding an aspect of human nature ahead of the competition.

But an insight into happiness is not – on its own – yet work. Work is everything we need to do to turn insights into stable, nameable, reproducible and ultimately tradeable things; to turn a particular kind of berry exposed to the sun into the tool we call a jam, a particular harmony into the tool we call a song, to turn a sequence of ideas into the tool we call a college course. Every pleasure needs to be ‘worked on’, farmed, pruned, cultivated and arranged into an assembly line.

When we think of all work as a matter of tool building, the distinction between art and commerce disappears in an illuminating way. In the 1880s, the largely deserted, rugged coast of Normandy was visited by the Impressionist painter Claude Monet. He was particularly attracted to the cliffs near the village of Etretat. Many local people and one or two rare visitors must occasionally have had the fleeting thought that this was a charming place – as they drew up a fishing boat on the sand or collected the iodine rich kelp. What distinguished Monet is that he sought to place his pleasures on a solid footing. He waited for hours from a variety of vantage points until just the right sort of light emerged from the reflections thrown up by the crashing of the waves – and then tried to arrest, fix and render more tangible his pleasure in a series of tools we now call ‘Impressionist paintings’.

A tool for enjoying the effects of reflected light on water, cloud and rock.

But receptive antennae, highly attuned to pleasures and pains, are not the exclusive possession of the people we call artists. Another way of capturing the beauty of the cliff faces of Normandy was pioneered by entrepreneurs who, in the latter part of the century, raised loans from Parisian banks in order to construct imposing static tools for appreciating views of cliffs – complete with large plate glass windows, bellboys and balconies – and that we call in shorthand ‘hotels’.

Hotel d’Angleterre, Etretat.

It’s in the nature of most tools that they can’t be made alone. Work is touching to behold when we see a wide variety of people, of different ages and temperaments, physical builds and capacities, united by a single aim; for example, when a gruff handyman, dour accountant, cheery instructor, bland marketing agent, severe government inspector and temperamental cook all come together to create the tool we call a school or a kindergarten. Given what we know of human nature – how conflictual, tricky and individual we can be – it is redemptive to see that we are also at points capable of laying aside our differences in the name of a unitary mission. Each of us considered singly may not be such an impressive thing but we rise to the grandeur of the projects we collectively engage in: a cathedral turns the humblest stonemason into a servant of the sublime.

At the same time, our work gives us an opportunity to escape from some of the normal difficulties of being ourselves. It imposes a requirement that we be ‘professional’, which might sound inauthentic and deceptive, but can in truth provide a welcome alternative to the intractable difficulties thrown up by our deeper selves. For a few hours, via our work, we can lay aside the doubts and agonies of our inner lives and experience a simpler, more one-dimensional but also more decisive and logical way of being. We can enjoy a professional atmosphere where not everyone feels it their duty to be an uncensored correspondent of their every mood. After an emotionally turbulent weekend, we may welcome Monday morning for the more straightforward image it returns us of ourselves.

At its best, work allows us to park what is most valuable about us – most creative, sensible, kind, perceptive – in an object or institution that is more stable and accomplished than we are. We may vacillate, get cross, fall into doubt, behave pathetically – but with any lucky, the tool we make will bear no trace of our weaknesses. The good tool gives no hint of the frailties of its maker. The very definition of sound work is that it should be better than the person who made it. It should also ideally not fall apart so easily. We have to die, but it might go on – continuing to deliver pleasure or alleviate pain when our name has long been erased. It constitutes a victory of sorts over the forces of entropy and extinction.

All this said, there is so much that can stop us from finding the work that would help us flourish. We might not have the courage to think about what is missing from the world or to follow any of our insights into the nature of happiness. We might fall back on a feudal mindset in which we assume that some people are allowed to develop their vision and others – by some arbitrary rule – are not. A hard, submissive childhood may school us in resignation. Without any plans, increasingly afraid of survival, we may panic and fall prey to the plans of others, losing sight of the contours of our unique mission.

The education system doesn’t help: for years, we are given instruction in a random range of skills but without an overview of what our lives might really amount to – and what work is ultimately about. We aren’t helped to fathom what we in particular are interested in and how it might map onto what is possible in the world. We lack a career counselling service that could combine detailed explanations of available work with help in understanding our feint and untrained signals of enthusiasm: a service that would track down the fertile zone in which the needs of the world and our aptitudes connect, a service to highlight the spark of genius inside every one of us – so that we might one day contribute to a tool that counts and die without regret.

The pain of modernity here as in so many other fields is that we have raised expectations without teaching ourselves how we might meet them, to have left ourselves unaided in a painful intermediate zone between expectation and reality. We need no longer toil like our ancestors. We have the right to discover the tools that could redeem each us even as we diminish the sufferings and raise the pleasures of strangers.