Leisure • Art/Architecture

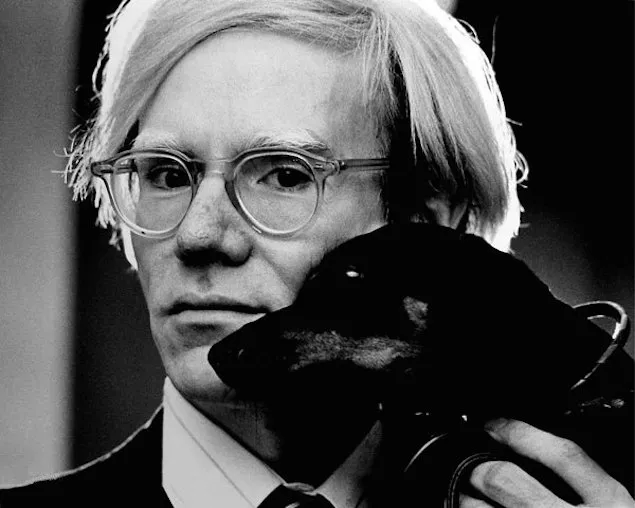

Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol was the most glamorous figure of 20th-century American art. He is famous for making prints of tins of Campbell’s soup and brightly-coloured portraits of celebrities like Marilyn Monroe and Michael Jackson. Much about his life was eccentric – he wore a silver wig; he liked to peel potatoes while lying in bed; he liked to go to the dry cleaners and stand in the corner, to enjoy the smells and sounds of the chemicals and cleaning machines. He loved airports, and used to go through airport security multiple times because he said he found it fascinating and inspiring.

Andy Warhol’s great achievement was to develop a generous and helpful view of two major forces in modern society: commerce and celebrity. He spent most of his life as an international celebrity, but he was also keen on business. Warhol was born in Pennsylvania in 1928 to Czechoslovakian parents and lived most of his life in New York. Today his name is one of the most commercially-successful artistic brands on the planet (his pictures of Elvis sell for 50 to 100 million dollars).

There are four big ideas behind Andy Warhol’s work, which can teach us a more inspired way of looking at the world, and prompts us to build a better society.

Appreciating everyday life

We spend much of our life working to reach some kind of better place: to have a nicer house, to buy better things, perhaps to move to a different country. We are often down on average things and positive about the exotic: a meal from Panama with Japanese infusions, a holiday in Tbilisi. It is normal to feel that the exciting things are not where we are.

Andy Warhol aims to remedy this by getting us to look again at things in everyday life. The soup can is an intriguing object.

Putting them on the wall and looking at them helps us to see their beauty, to notice their appealing labels, their strong but elegant form, perfectly fitted to their job. When they are in a picture, we look at them with the same interest we might bestow on a candlestick holder or a spoon dug up from Roman times. Art can put us in the mindset of appreciation, which is hard to hold onto when we are busy using or consuming the objects around us.

In the same spirit of re-directing our attention, Andy Warhol made a video of himself eating a hamburger.

He is trying to get us to practice a mental habit: feeling that the things we do in our daily life are interesting and worthy of note. Warhol wants us to realise that we are already living an appealing life – to stop being down on ourselves, and ignoring ordinary experiences – filling up a car with petrol, dropping something off at the dry cleaners, microwaving a pre-made meal… We don’t need to fantasise about other places. We just need to see that the things we do all the time and the objects around us have their own merits and are enchanting in their own ways.

Creating celebrities

During the 1960s, Warhol groomed a retinue of bohemian and countercultural eccentrics to whom he gave the title ‘Superstars’, including Nico, Joe Dallesando, Edie Sedgwick, Viva, Ultra Violet, Holly Woodlawn, Jackie Curtis, and Candy Darling.

Warhol understood that celebrities have an important power: they can distribute glamour and prestige. He thought that glamour needed to be distributed in the right way for society to work well.

For example, Warhol believed that the job of being a maid had too little status. He wrote: ‘They should have a college course now for maids and call it something glamorous, I think. People don’t want to work at something unless there’s a glamorous name tagged to it. The idea of America is theoretically so great because we’ve gotten rid of maids and janitors, but then, somebody still has to do it. I always think that even very intelligent people could get a lot out of being maids because they’d see so many interesting people and be working in the most beautiful houses. I mean, everybody does something for everybody else – your shoemaker does your shoes for you, and you do entertainment for him – it’s always an exchange, and if it weren’t for the stigma we give certain jobs, the exchange would always be equal. A mother is always doing things for her child, so what’s wrong with a person off the street doing things for you?’

Warhol suggested that the President could use his status to shift perceptions. ‘If the President would go into a public bathroom in the Capitol, and have the TV cameras film him cleaning the toilets and saying “Why not? Somebody’s got to do it!” then that would do so much for the morale of the people who do the wonderful job of keeping the toilets clean.’

Warhol saw that celebrity culture has great potential. But he wants us to get the right celebrities. If we were to anoint some ‘Superstars’ today we might choose, for example, a nurse, a janitor, an airport security manager, an engineer in a logistics warehouse, a philosophy student, an economist, or an 11-year-old who has just started drawing classes.

Combining art and business

He didn’t call his place in New York a studio – the prestigious term used by artists since the Renaissance to describe their place of work. Instead he called it ‘The Factory’.

Warhol in the Factory, 1965

We tend to feel that the idea of art and the idea of a factory don’t mix. But Warhol’s point was that business and art actually do very much belong together: ‘Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art. During the hippie era people put down the idea of business – they’d say, “Money is bad,” and “Working is bad,” but making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.’

He began to like business when he made an agreement with a local theatre to make them one film per week. This moved his filmmaking from being something done on the side, to an organised production. He learnt more skills, and moved from short movies into longer movies and feature films (he also tried to learn the logistics of distributing movies, but decided he needed a partnership after all).

The lesson of The Factory is that we can organise ourselves to produce good things more reliably and cheaply. One example of this for Warhol was Coke. He pointed out that wherever you go, Coke is always the same. Whether you’re the President or a cleaner, you still drink the same Coke – and it’s a good drink. Art has generally not been able to live up to this ideal of being good and widely distributed. Artists make a few things, and only a few people get to own them. Andy Warhol tried to counteract this. One day after reading that Picasso had made four thousand masterpieces in his lifetime, Warhol set out to make four thousand prints in one day. As it turned out, it took him a month to make five hundred. But he believed that art should be mass-produced and widely distributed. ‘If the one ‘master painting’ is good, they’re all good’.

Andy Warhol with ‘The American Man (Portrait of Watson Powell)’ at The Factory, 1964

The lesson we can draw from Warhol is that mass production needs to apply beyond making prints and other kinds of ‘high art’. We need the organising, commoditising and branding powers of business to reliably produce and distribute good clothing, high-quality childcare, psychotherapy, careers advice, and good architecture – to start the list.

Brand extension

Most art does not have an impact on the world. But Warhol was keen to do so. He mastered many genres – from drawing, painting and printing, to photography, audio recording, sculpture and theatre; he started a magazine, designed clothes, managed a band, made 60 films and had plans to start his own TV chat show. What held all this together was his approach to life, which came through in everything he did. He was sensitive: he noticed details, he was aware of how he felt, he was moved by the surfaces of the world. He was also kind: he was unbullying. He was not vindictive against the world. He was untroubled by people’s strangeness. This openness and lack of vindictiveness gave him freedom to play and enjoy the world.

Ethel Scull 36 Times

All these values together make up his ‘brand’. ‘Brand extension’ means taking the values which have been realised in one thing, and making them real in another thing. For example, if we looked at the values embodied in the VW Golf car – we might say that it is a car which is unaware of class distinctions, practical, elegant, affordable. These qualities are needed in many places elsewhere in the world. Brand extension might take VW from making cars, to designing clothes, or setting up a school.

Warhol was able to extend his work into different channels partly because of his populism. Being populist means he was unafraid to reach people where they started. The chat show is populist because it plays to what masses of people find funny or interesting. Warhol was populist out of generosity. He wanted to translate the things he cared about (sensitivity, love of glamour and spectacle, playfulness) into objects and experiences that touched many people.

The only pity is that he finished where he did. He could have founded his planned TV chat show, then gone on – in ever broader and broader partnerships – to start a fashion label, design a hotel, a chain of schools, a financial advisory service, a medical centre, a supermarket chain and an airport…

This is the task still open to people who are drawn to art, but also want to change the world.

He died in 1987 when he was only 58, after complications following routine gallbladder surgery in New York Hospital. He is buried at a small cemetery near where he was born, in Bethel Park, Pennsylvania.