Leisure • Eastern Philosophy

Gongshi

In the West, we expect philosophy to come from books. In the East, more wisely, there’s an awareness that it may legitimately come from rocks as well. In China, in the middle period of the Tang dynasty, at some point in the first half of the 9th century CE, an enthusiasm for rocks developed in Chinese culture which gradually spread to Japan and Korea – and has continued to the modern age. Rocks mounted on wooden stands have become well-known and prestigious objects of contemplation.

In East Asia, rocks are venerated with all the respect that we would accord to a work of art; except that what is really being honoured is the power of nature rather than the human hand. The more eroded and irregularly contorted the rock, the better.

Collectors seek out rocks with passion. Scholarly essays and whole treatises are dedicated to the subtleties and nuances of rocks. Rocks from different locations are catalogued, and their particular aesthetic qualities inventoried and graded. Smaller rocks are placed on desks; gardens are built around the larger ones.

What follows is a brief history of petrophilia (love of rocks):

826 CE, Tang Dynasty

Lake Tai, Jiangsu Province, China

A middle-aged gentleman is taking a stroll around a large lake on the Yangtze Delta Plain in eastern China, when something on its shore catches his eye. It is an apparently trivial yet momentous discovery: a pair of oddly shaped rocks.

This is perhaps no less than the founding moment in Chinese petrophilia. This cultivated pedestrian is someone special. After numerous ups and downs in his career as a state official, including periods of imperial disfavour and exile, Bai Juyi has finally made it: he has been appointed Prefect of the nearby city of Suzhou. He also happens to be one of China’s major poets.

It is not a chance combination of talents. Examinations to enter the state administration test the candidate’s knowledge of poetry as well as the classics of Chinese philosophy. Culture is believed to inculcate moral virtues of sensitivity, rectitude and wisdom that are essential to judicious decision-making. The ideal administrator doesn’t just know maths and time-keeping, he is meant to be a man of learning and the arts. Many of China’s leading poets and painters have careers in public service.

So struck is Bai Juyi by these rocks, with their twisted angles and perforations, that he has them taken back home to Suzhou. Soon after his return, he sits down and writes a poem about them.

Poetry for Bai Juyi is often a kind of a diary writing, in which he recounts interesting experiences and powerful feelings that affect him during the day. The title for this particular poem is ‘A Pair of Rocks’. Bai Juyi admits that the rocks are somewhat unconventional in their aesthetic appeal:

Dark sallow, two slates of rocks,

Their appearance is grotesque and ugly.

They are also covered in dirt and begrimed with smoke, their cavities thick with green moss. He describes himself washing and scrubbing them:

Of vulgar use they are incapable;

People of the time detest and abandon them.

So just what is the value of these unprepossessing specimens? Daoism, which began as a philosophy in ancient China before turning into a popular religion, cherishes nature – and it is evidence of its force that Bai Juyi welcomes in the rocks. The holes, perforations and indentations signal the patient, mighty forces of the universe – which we should respect and attempt to find harmony with.

The ancient rocks offer a consolation for an ageing Bai, who feels excluded from ‘the world of youngsters’:

Turning my head around, I ask the pair of rocks:

‘Can you keep company with an old man like myself?’

Although the rocks cannot speak,

They promise that we will be three friends.

Through rocks we can learn to respect the dignity of what has been marked by ageing and time. Thanks to Bai Juyi’s enthusiasm, the unusual limestone rocks at Lake Taihu soon become sought after by sensitive, creative people in the Tang dynasty.

12th century CE, Northern Song dynasty

Wuwei district, Anhui Province, China

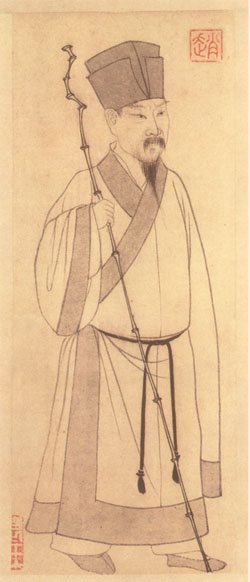

It is early in the first decade of the twelfth century. Mi Fu, the most legendarily eccentric of scholar-officials in China, has just been appointed as a magistrate in Wuwei County. On arrival, he has to pay an important social visit. He has been invited to meet-and-greet all the other important administrators with whom he will be working. They stand waiting for him in the front garden of the official residence. But as he walks towards them, they are shocked at his sudden breach of protocol.

For he has been stopped in his tracks by an unusually large rock in the garden. Instead of offering his respects to his hosts, Mi Fu turns and bows ceremoniously to the extraordinary looking rock. He calls out and addresses it as ‘Elder Brother Rock’, making an elaborate speech. He performs all the rites and obeisances that were prescribed for an older brother according to the principles of ‘filial piety’ in Confucianism – which believed that harmony in the family was the nucleus of social order in the state at large.

Only after fully expressing his devotion to this amazing rock does Mi finally turn to his flabbergasted hosts. It was this story that earned Mi Fu his soubriquet, ‘Crazy Mi’ – and captured the imagination of East Asia’s painters, for whom ‘Mi Fu and Elder Brother Rock’ remained a favourite image for centuries to come.

In Confucianism, natural objects were perceived to have moral qualities analogous to human virtues – the uprightness of the bamboo or pine tree, for example, withstanding the buffeting wind, was a model for the rectitude and probity an official should display in government. Mi Fu takes this to an extreme – the natural is not just a paradigm of official virtue, but is of equal, even superior, importance to social responsibilities.

Mi Fu writes a treatise on rocks that enumerates their four main aesthetic qualities: shou, an elegant and upright stature; zhou, a wrinkled and furrowed texture; lou or cracks that are like channels or paths through the rock; and tou, the holes in the rock that allow air and light to pass through.

In the 11th and 12th century, during the Chinese Northern Song dynasty, the passion for collecting rocks among scholar-officials like Mi Fu takes off in earnest. Stones are mounted on wooden bases and placed on desks as constant sources of inspiration.

These decorative stones become known as gongshi – spirit stones (popularly mistranslated as ‘scholars’ rocks’ in English). Their peculiarly twisted shapes are admired as evidence of the qi energy that is believed to animate nature and the human body alike.

Any cultivated person is expected to have an appreciation of rocks. They are valued as highly as any painting or calligraphic scroll. The well-known Song dynasty scholar-statesman, Su Shi, for example, is said to have offered a set of stones as a fair and equal exchange for a set of great paintings.

During the Song dynasty, the most favoured rocks are quarried from the limestone of Lingbi, in the northern Anhui province. Lingbi rocks are dark black and glossy in texture. They are esteemed as much for the bell-like sound they produce when tapped as for their striking appearance.

Lingbi Rock

January, 1127 CE, end of the Northern Song dynasty

Kaifeng, Northern China

The imperial capital of China, Kaifeng, is under siege and about to fall to the Jurchens, a nomadic people from Manchuria. Soon the Song emperor, Huizong, will be taken captive and forced to abdicate, while his son, Qinzong, will flee to the south to establish a new court and the Southern Song dynasty. China will be split in two. In these desperate final days of the Northern Song, the order is given for the trees in Huizong’s spectacular imperial garden at Kaifeng, the ‘Northeast Marchmount’, to be cut down for firewood, and for its incredible array of fabulous rocks to be pulled out of the ground and used in catapults against the invading Jurchens. It is a sad end to what must have been one of the most remarkable gardens in world history.

The royal park is said to have been teeming with striking rocks. The most prominent have been given names by Huizong, and commemorated in verses by him, incised into the rocks in golden ink. There is one rock called ‘Divine Conveyance Rock’, another ‘Auspicious Dragon Rock’.

Emperor Huizong’s passion for rocks has clearly rather got out of hand – and explains his neglect of security issues. Huizong had in previous years appointed a royal official to explore the whole of China in search of precious rocks for his garden. Apocryphal tales abound of this official’s abuses – such as robbing homes for the sake of rocks, and dismantling important bridges to let boats with huge rocks pass by on canals and rivers. A love of rocks appears to have hastened the collapse of the Northern Song empire.

1450-1550, Muromachi Period, Japan

Ryoanji Temple, northwest Kyoto

In fifteenth-century Japan, a new type of rock garden develops. As with so much of Chinese culture, the obsession with rocks has crossed over to Japan in the latter part of the first millennium – while also being adapted in special ways. In Japan, the spirit rocks are called suiseki, and the Japanese favour much more subdued, smooth rocks than the Chinese. In Japan, rocks are treasured for their yoseki, a weathered and ‘ancient’ appearance that is similar to the ‘aged’ simplicity of the aesthetic of wabi sabi. The rocks are not so much placed on wooden stands, as positioned in trays surrounded by sand or water – evoking mountains and lakes.

At several Zen Buddhist temples, and most remarkably at Ryoanji in Kyoto, the stones start to be set in very more minimal settings, so as to bring out their qualities all the more.

Here landscape is reduced to its barest essence – scattered rocks that recall mountains surrounded by the stone fragments of raked gravel in symmetrical wave-like patterns that suggest flowing water. The only greenery is the bed of moss in which each rock is set.

The raking of the gravel around the rocks by temple monks is a careful and precise art. There are various patterns including the ‘water pattern’ of concentric rings or ripples, like those produced when a stone is dropped in a lake; the ‘stormy water pattern’ of haphazardly overlapping semi-circles, and the continuous wave-effect of parallel or gently undulating lines.

Marked off by a wall, the garden of Ryoanji is to be viewed while seated from outside rather than physically explored.

Conclusion

The originator of the East Asian reverence for rocks, Bai Juyi, was well aware of how powerful a love of rocks can become. In his essay, ‘Account of the Lake Tai Rock’, he speaks of an ‘addiction’ that some rocks can bring about. Truly wise people should restrict their rock worship to a few hours a day, he counsels.

At a time, when few of us spend more than a few minutes a year looking at a rock, the advice seems less than urgent. Indeed, the tradition of rock reverence has a lot to teach us: that wisdom can hang off bits of the natural world just as well as issuing from books; that we need to surround ourselves with objects that embody certain values we’re in danger of losing sight of day-to-day – and that some of our most precious moments can be spent in the presence of nothing more chatty, prestigious or costly than a rock.