Work • Politics & Government

Africa after Independence

The 6th of March 1957 was set to be one of the most joyous and memorable days in the history of modern Africa; this was the date on which Britain finally agreed to give Ghana, the richest and best administered of all African colonies, its independence. Britain was the first European power to realise that colonialism was practically and morally unsustainable – and, with good will on both sides, it was peacefully letting Ghana go.

The new country, under its intelligent and charismatic 47 year old leader Kwame Nkrumah, pulled out all the stops. There were six days of celebration, with garden parties, dance displays and a Miss Ghana competition. Dignitaries from almost every nation flew in; US Vice President Richard Nixon came and the British Queen was represented by her aunt, the Duchess of Kent. At precisely midnight, the Union Jack was lowered and replaced with a new flag of Ghana; three horizontal stripes of red, gold and green with a black five pointed star in the middle. Nkrumah told cheering crowds: ‘We can prove to the world that when the African is given a chance, he can show the world that he is somebody! …We have awakened. We will not sleep anymore.’

The Duchess of Kent, seated center on dais, reads a message from the Queen of England in the Parliament House at Accra, Ghana, on March 6, 1957, Independence day.

In the next three decades, forty seven African countries would become independent – some very peacefully, others only after the most desperate and bloody conflicts with reluctant colonial regimes. Whereas in 1930, only one African country – Ethiopia – had been independent, by the end of the century, every single nation had gained its freedom.

TIMELINE OF INDEPENDENCE

47 countries gain independence between 1957 and 1990

| Country | Independence Date | Colonist |

| Ghana, Republic of | March 6, 1957 | Britain |

| Guinea, Republic of | Oct. 2, 1958 | France |

| Cameroon, Republic of | Jan. 1 1960 | France |

| Senegal, Republic of | April 4, 1960 | France |

| Togo, Republic of | April 27, 1960 | France |

| Mali, Republic of | Sept. 22, 1960 | France |

| Madagascar, Democratic Republic of | June 26, 1960 | France |

| Congo (Kinshasa), Democratic Republic of the | June 30, 1960 | Belgium |

| Somalia, Democratic Republic of | July 1, 1960 | Britain |

| Benin, Republic of | Aug. 1, 1960 | France |

| Niger, Republic of | Aug. 3, 1960 | France |

| Burkina Faso, Popular Democratic Republic of | Aug. 5, 1960 | France |

| Côte d’Ivoire, Republic of (Ivory Coast) | Aug. 7, 1960 | France |

| Chad, Republic of | Aug. 11, 1960 | France |

| Central African Republic | Aug. 13, 1960 | France |

| Congo (Brazzaville), Republic of the | Aug. 15, 1960 | France |

| Gabon, Republic of | Aug. 16, 1960 | France |

| Nigeria, Federal Republic of | Oct. 1, 1960 | Britain |

| Mauritania, Islamic Republic of | Nov. 28, 1960 | France |

| Sierra Leone, Republic of | Apr. 27, 1961 | Britain |

| Nigeria (British Cameroon North) | June 1, 1961 | Britain |

| Cameroon(British Cameroon South) | Oct. 1, 1961 | Britain |

| Tanzania, United Republic of | Dec. 9, 1961 | Britain |

| Burundi, Republic of | July 1, 1962 | Belgium |

| Rwanda, Republic of | July 1, 1962 | Belgium |

| Algeria, Democratic and Popular Republic of | July 3, 1962 | France |

| Uganda, Republic of | Oct. 9, 1962 | Britain |

| Kenya, Republic of | Dec. 12, 1963 | Britain |

| Malawi, Republic of | July 6, 1964 | Britain |

| Zambia, Republic of | Oct. 24, 1964 | Britain |

| Gambia, Republic of The | Feb. 18, 1965 | Britain |

| Botswana, Republic of | Sept. 30, 1966 | Britain |

| Lesotho, Kingdom of | Oct. 4, 1966 | Britain |

| Mauritius, State of | March 12, 1968 | Britain |

| Swaziland, Kingdom of | Sept. 6, 1968 | Britain |

| Equatorial Guinea, Republic of | Oct. 12, 1968 | Spain |

| Guinea-Bissau, Republic of | Sept. 24, 1973(alt. Sept. 10, 1974) | Portugal |

| Mozambique, Republic of | June 25. 1975 | Portugal |

| Cape Verde, Republic of | July 5, 1975 | Portugal |

| Comoros, Federal Islamic Republic of the | July 6, 1975 | France |

| São Tomé and Principe, Democratic Republic of | July 12, 1975 | Portugal |

| Angola, People’s Republic of | Nov. 11, 1975 | Portugal |

| Western Sahara | Feb. 28, 1976 | Spain |

| Seychelles, Republic of | June 29, 1976 | Britain |

| Djibouti, Republic of | June 27, 1977 | France |

| Zimbabwe, Republic of | April 18, 1980 | Britain |

| Namibia, Republic of | March 21, 1990 | South Africa |

There were to be many more independence days, celebrations, national anthems and hopeful speeches. But despite the optimism, the early dreams of independence were, in nearly all cases, to be violently and gravely frustrated. New nations that had begun with great ambitions became mired in corruption, warfare, plunder, disease, maladministration, and – in many cases – genocide. Nkrumah ended up ruining the economy of Ghana, enriching his cronies, imprisoning his enemies and was finally deposed in 1966 by a military coup while on a trip to Beijing. By the start of the 21st century, Africa was the poorest continent, its countries at the bottom of all indexes for development, health, welfare and freedom. Per capita income had either stagnated or in some cases had fallen over decades. Half of the continent’s population lived on less than a dollar a day; between 1981 and 2002, the number of its people in poverty doubled; its food production fell by ten percent.

How had things turned so sour? Why were the dreams of independence so systematically dashed? It might seem mysterious, but looked at more soberly, the problems were in many ways to be anticipated from the start; they were in large part the legacy of colonialism. African nations ran into so many difficulties because they had been dealt some truly appalling cards long before a single independence flag was ever raised.

We can identify a range factors that explain Africa’s painful post-independence history:

1. Countries with Straight Lines

The single greatest problem was that most countries we know in Africa today were invented out of thin air by colonial powers. There was, before the arrival of Europeans, no such territory as ‘Nigeria’ or ‘Mali’, ‘Namibia’ or ‘Gabon’; these were arbitrarily made up places designed to suit European priorities. These nations pushed together ethnic groups that had over centuries usually had nothing to do with one another, spoke different languages, worshipped different religions and had long histories of rivalry and suspicion: it was as if someone had, for example, decided to create a new country out of a bit of Greece, a slice of Germany and a swathe of Finland – and then wondered why things didn’t work out too well.

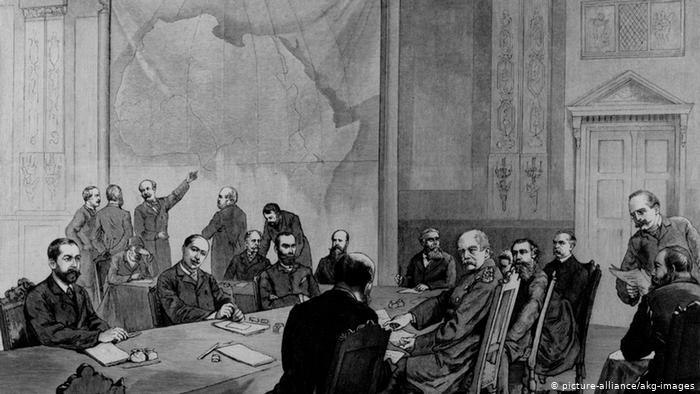

Up until 1870, the European presence in Africa had been limited to a few coastal ports and their surrounding regions. Then, over the next forty years, in a vicious process euphemistically known as ‘the Scramble for Africa’, Europe decided to lay claim to the whole continent, attracted by the idea of stripping it of all its mineral wealth while using it as a market to dump its excess goods. The carving up began in earnest at a conference held in Berlin in 1884. In the Reich Chancellery, a gigantic map was put up on the wall, showing all of Africa’s natural features, but leaving out all place names, let alone references to ethnic groups, religions or languages. Over three months, delegates from the main European powers haggled and bartered over gold mines and plantations, copper deposits and forests set in what they cynically assumed to be a more or less unowned landscape. They took out their rulers and drew straight lines over territory, seventy percent of which no European had ever set foot in. Not a single African was invited to the meeting.

The new countries that emerged from this delusional process destroyed any possibility of Africans’ easily developing a sense of true belonging or patriotism. For example, the borders of modern Burkina Faso divide up territory that traditionally belonged to twenty-one different cultural and linguistic groups. The Ewe people, who have a five hundred year history were split between Ghana and Togo. In the horn of Africa, the Europeans split the Somali people into French Somaliland, British Somalia, Italian Somalia, Ethiopian Somalia, and the Somali region of northern Kenya. The Afar people of Ethiopia were partitioned into Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Djibouti and the Anyuaa and Nuer were split between Ethiopia and South Sudan. The result has been constant tribal conflict within countries and across borders as divided peoples attempt to regain their lost unity.

A simple rule of thumb when trying to determine the difficulties an African country will face is to take a look at how straight its borders happen to be. The straighter they are, the more likely it is that the Europeans drew a line through existing tribes or kingdoms – and the result will be chaos and civil war; the more wiggly they are, the more likely it is that an old tribal arrangement has been respected and therefore, that a country will be a little more internally stable and cohesive. Take Botswana, the richest, least corrupt and most democratic country in Africa. Note that it has wiggly borders on three of its four sides and that it is home to just one ethnic group, the Tswanas, who had lived within the modern nation’s borders for many centuries. Compare this fortunate country with Equatorial Guinea, which is all straight lines and has a majority ethnic group, the Fangs, who are divided up between neighbouring Cameroon and Gabon. As a result, Equatorial Guinea has been continually unstable (despite being blessed with oil), is at or near the bottom of all development tables and has an infant mortality rate of 25% (it’s probably about 2% where you’re reading this).

We can conclude that it is never a good idea to make up a country with a ruler and map. Countries are like families. We put up with a lot when they are our own – and we almost never push things too far. Groups of strangers owe each other no such loyalty. European colonialists made many errors, but none was quite so great as forgetting that Africa already had countries and didn’t require a group of foreigners to erase most of them and make up a whole new set for them.

2. The Government is the Enemy

Because of the way that African nations had originated, once they achieved independence, their peoples generally felt a very low sense of allegiance to the central government, which was tainted with memories of the old regime. It was hard to feel much love for a ‘nation’ that had been spirited into being by one’s oppressors.

For example, the nation we know as the Democratic Republic of the Congo occupies territory that had been stolen from a variety of ethnic tribes by Belgium in the 19th century. The colonialists behaved with particular brutality in the country they called the Belgian Congo, killing hundreds of thousands of people on plantations and chopping off arms and legs of those suspected of not working with sufficient energy to enrich the Belgian monarchy.

Once the Belgians left, the country – now flying a new flag of the Democratic Republic of the Congo – was quickly overrun by a variety of strongmen, mercenaries and army leaders. Any time an ordinary citizen came close to an institution of central government, their impulse was either to destroy or evade it. One didn’t in the process feel disloyal to something good and community-minded; one was taking revenge on a source of evil.

To a lesser extent, this was the impulse in almost all the new nations of Africa. The government was not seen as a benevolent organ that existed in order to enhance everyone’s welfare: it was the enemy that needed to be escaped from and cheated. The goal was to avoid paying taxes, obeying laws or serving in the military, let alone having to lay down one’s life for the nation.

3. Leaders Who Didn’t Love their Countries.

It wasn’t just the people who hated the government; rulers seemed to show equal disdain for their people.

The rulers of post-colonial Africa numbered some exceptionally corrupt and monstrous figures: there was Jean-Bédel Bokassa, president, and self-proclaimed emperor, of the Central African Republic between 1966 and 1979. His country was blessed with huge natural advantages, uranium, oil, gold, diamonds, cobalt – as well as ideal land for agriculture. And yet it remains one of the poorest places in the world, ranking 188th out of 189 countries in terms of its human development. A lot of the responsibility lies with Bokassa who for decades plundered his country, with the cynical connivance of France, its former colonial ruler, because it badly needed his uranium to run its nuclear power stations. Bokassa’s most infamous moment was his coronation as emperor, a display which went on for two days, cost 25 million dollars (a quarter of the country’’s annual budget) and featured Bokassa sitting on an eagle-shaped solid gold throne.

Bokassa’s time eventually ran out when schoolchildren started spontaneously rioting because he had ordered them to wear expensive uniforms with his image on them made in a factory run by one of his relatives. He had the children arrested and sent into the cellars in his palace. There his guards beat 100 of them to death; Bokassa was reported to have come down and done some killing himself, striking the youngsters with his ivory cane. Such was the outrage, Bokassa fled into exile.

If only he had been a one off. There was Gnassingbé Eyadéma, President of Togo between 1967 and his death in 2005. An egomaniac, he had to be constantly surrounded by a 1,000 women who had to dance in praise of him. Every shop in the country had to have his picture on the wall. He tortured his enemies, neglected all education and infrastructure, and was said to have made off with a billion dollars of his nation’s wealth. Then there was Omar Bongo, President of Gabon between 1967 and 2009, a ruler who owned 39 houses around the world and had US$130 million of his nation’s wealth in his personal bank account. There was Francisco Nguema who ruled Equatorial New Guinea between 1968 and 1979, during which time a third of the population fled or was exiled. He developed a paranoia against anyone who seemed educated; wearing glasses or having a book in the house could have you killed as an ‘intellectual’. He kept half of his nation’s wealth under his bed in a hut in his ancestral village. There was General Sani Abacha of Nigeria (1993 to 1998) who stole $4.3 billion from the government. There was Mobutu Sese Seko of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (1965-1997) who created a one party state based on his worship and made off with $5 billion dollars from the central bank. He built a palace for himself costing a hundred million dollars in his ancestral village of Gbadolite, 700 miles north east of the capital Kinshasa. It was 15,000 square meters in size, made out of Carrara marble from Italy and there Mobutu hosted the Pope, the French president and the Director of the CIA. Mobutu loved shopping and regularly charted Air France’s Concorde to take him and his wives and aides to Paris. He had a 3200m long runway especially built to take the supersonic jet. The nearby village lacked electricity or paved roads, let alone a school or a doctor.

In 1985 a famous French chef, Gaston Lenôtre, flew into the country on Concorde with a birthday cake – chocolate, cream, noisette paste and strawberries – that he had especially made for Mobutu. Half the population of the country couldn’t feed themselves properly.

It isn’t as if all corrupt African leaders stay in power forever. Eventually, the citizens and the army get fed up – and a coup is launched. In 48 independent, sub saharan African nations, between 1956 and 2001, a 46 year period, there have been 80 successful coups d’etat and a 108 failed ones. The problem is that almost no good government ever emerges from a coup. One terrible leader simply gives way to another. The new leader doesn’t have better motives for their country, they just think it’s their turn to go shopping.

4. A Lack of Trust

One way to capture the difficulties of Africa is to say that in many of its countries, there is a crisis of trust. What is the point of investing in a new factory, if a ruler might suddenly throw you in prison for no good reason? What is the point of working hard for a degree, if the job will go to someone else? Why pay taxes if one knows they’re simply going to pay for a birthday cake for a tyrant?

Corruption runs right through the system. If you’re stopped at the traffic lights by the police, they’re likely to ask you for a bribe; a doctor won’t see you until you’ve paid a bit extra to the receptionist. Your exam results aren’t going to be great until you’ve been able to find some money to pay off the teacher. Everything becomes exhausting and extremely dispiriting.

Those who want to help African often miss where the problem starts. They look at a village and notice that the pump is broken and the road isn’t paved – and so, very nicely, they’ll fix these things for the village. But the issue started somewhere else. The government had the money to help the village, it’s just that the money was spent on a private jet or a dance party. Arguably, by coming in and paying for the village, foreign aid workers are unwittingly helping corrupt rulers not to have to face the legitimate anger of their own people.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 55% of the budget disappears in corruption every year, that’s USD15 billion. This isn’t a poor place, the value of the DRC’s unexploited minerals is estimated at USD24,000 billion; it’s just a desperately badly administered and corrupt place. A country that could easily afford health care, an education system, a fire brigade, and government-run ambulance service has none of these. So pervasive is the corruption, the people have developed a special set of terms for it:

madesu ya bana (‘ beans for children’)

sucré or bière (soda or beer)

sehemu yangu (‘ my part’, that is, your share of any deal)

To show the eventual connection between poverty and corruption, we need only look at a map of the world’s most corrupt countries; they are almost all also the poorest countries. Honesty isn’t only morally good; it is what makes you and your country very rich.

5. The Clan Comes First

But there is one thing to add on the issue of corruption. Many people who behave in what we call a corrupt way in Africa don’t see it that way. They think they are doing the right thing; they believe they are being good.

It is the custom in many nations, as soon as you come into a powerful job or get some money, that you will immediately dispense favours to your family. If you’re the chief of police, of course you should give jobs to all your relatives. If you’re the head of the central bank, naturally you have to give some ‘presents’ to everyone in your clan. People will constantly give jobs and favours to members of their own group as opposed to those who might be most technically proficient or deserving. You should always ask your uncle who has barely finished secondary school to run the hydroelectric dam over a trained engineer you don’t know.

We are so used to calling this corrupt that we are liable to miss a nuance. In Africa, what is truly corrupt and frowned upon is not to reward your family when you come into power. It would be as sinful in some sub-Saharan countries to reward strangers as, in many northern countries, it is problematic to promote your own family.

We may well call Africa inefficient, but we should be careful when we use a word like corrupt. What can seem like corruption to us may, in other eyes, just be common decency in looking after your family’s needs. It’s a pity that this nevertheless has such appalling results for the whole country.

Western countries have grown rich on the back of a very odd and counter-intuitive idea: the idea of not giving favours to your family and letting the best person win, not the one you’re related to. It might sound cruel, in fact, it helps every family in the country to prosper.

CONCLUSION

It can look as if the poverty of Africa is somehow natural and inevitable. It is anything but. This should be one of the richest continents in the world, the resourcefulness of its people and the richness of its natural assets is unparalleled – if only USD148 billion wasn’t lost to corruption every year.

The problem of Africa lies in the hollowness of its institutions; in the way that the police and law courts don’t function, contracts can’t be honoured, investment isn’t safe, and qualifications aren’t reliable.

Medicines and food may be needed in certain parts, but even more urgently required is the good governance that could over the long-term ensure that medicines and food would always be available.

But we also know where the problem started: corruption is a consequence, created by colonialism, of countries that in too many cases aren’t sufficiently loved by their own people or rulers; the family or clan come first, the nation can be cheated.

Africa will be sure to reach its true potential when its governments trust its peoples and its peoples trust (and deserve to trust) its governments.