Work • Consumption & Need

What the Luxury Sector Does for Us

A substantial portion of the modern economy is devoted to the production and sale of what are commonly referred to as luxury goods; the ‘luxury sector’ is estimated to comprise as much as 20% of the GDP of the world’s 20 richest nations. It is in this sector that we can observe humans doing something rather unusual: paying more for things than they strictly have to; investing more than is absolutely necessary in the business of travelling from A to B, protecting themselves from the cold or providing a receptacle for keys, phones and a purse.

That said, we shouldn’t associate luxury goods merely with sky-high prices; that would be to reduce a useful term unnecessarily. We should take it to refer simply to any kind of purchase where we are paying somewhat more than we would need to if we were solely fulfilling a material need – and where something else, something more psychological, appears to be motivating our behaviour. We are involved in luxury purchases when we want not just any stapler, but a very particular, slightly costlier one with an intriguingly moulded upper body; and not just any coat, but that one with the cashmere collar and jade-coloured buttons. What properly defines luxury isn’t a high price per se but a price that is higher relative to other goods in a category. We could, by this definition, speak of luxury socks and luxury butter, luxury envelopes and luxury pencils.

It is traditional to associate the purchase of luxury goods with greed, or a desire to show off – but this approach entails an enormous loss in our capacity to understand the real drivers of the economy and the nature of our appetites. The way we buy ‘luxurious’ things belongs to a project long associated with philosophy: that of defining and communicating our identity; that of knowing and then letting others know who we are.

The birth of the luxury sector can be traced back to 18th-century England. It was then that revolutions in production and a rise in income for the first time allowed a sizeable share of the middle classes a freedom to choose from among a range of goods and services. Suddenly, one could pick one of many kinds of soup tureens or lamps, side-tables or sherry glasses – and in doing so, had to ask oneself a new kind of question hitherto absent from the act of purchase: who am I in the world of objects?

Whenever we survey options for our possessions, we are at heart searching for items that will ‘fit’ our identities. We are looking to find versions of ourselves in a physical idiom. Every material object simultaneously possesses a psychological identity, which we have a powerful though usually somewhat unconscious sense of. The phenomenon can already be observed in something as apparently simple as our relationship to fonts:

We could, if asked, swiftly arrive at an intuitive sense of the different personalities on offer: Verdana feels contemporary, unfussy and democratic – whereas Cambria emphasises tradition, modesty and a certain politeness. They are two fonts and at the same time, two kinds of people. If we were asked to choose a font for ourselves, we would instinctively try to generate a match between letters and our own characters. We would be searching for a version of ourselves in the world of fonts.

Exactly the same concerns might be at work when we choose an alarm clock. Here too we would be looking to find a fit between a time-piece and an aspect of our inner selves and might reject a succession of options not because they didn’t tell the time well, but because they were betraying who we felt we were.

Searching for ‘me’ in the world of alarm clocks.

There is frequently an ‘aspirational’ quality to the way we go about settling on objects. The word is tricky, and is usually interpreted from a monetary and status point of view, as if the only things that any of us ever aspired to be was rich and important. But in truth our aspirations stretch far beyond this; to be aspirational in our purchases just means that we are aspiring to buttress, or concretise, aspects of ourselves that may at present still be evanescent or feint. This can mean any number of psychological features. We might be aspiring to build up such qualities as calm or intelligence, reliability or cosiness. The objects we buy tell us not just who we are, but also who we want to be but perhaps aren’t quite yet.

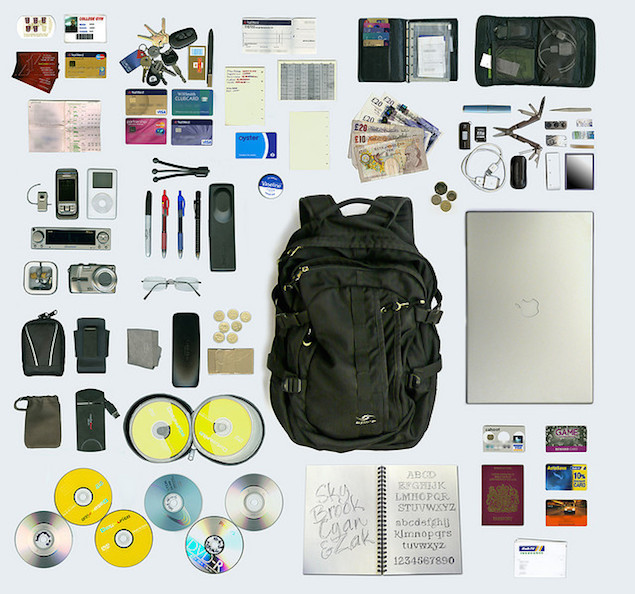

Material objects matter deeply because we generally find it very hard to tell people about ourselves. Our acquisitiveness is seldom greed, it is an urge to tell others what we value. There may be few opportunities to do so other than through things: words can be hard to find and others are in a hurry. We are lent important assistance in our communicative urge by our clothes, our cars, our watches, our kettles and our glasses. Almost everything we consciously pick for ourselves is involved in the tricky task of defining our identity and conveying it to others. We are looking for our possessions to remember and then eloquently convey to the world who we are and long more firmly to be.

A fair sense of what is at stake in our possessions dignifies the act of shopping – and suggests how much work we still have to do to help the process go right. To shop well emerges as a quasi-philosophical process dependent on an awareness of who we might be and in turn, what identities the objects on offer are proposing to us. The way in which we discuss shopping rarely bothers to delve as far as this: customer reviews tell us how objects perform materially or technically, but precious little attention is ever paid to what our cars or lamps, pens and phones are talking to us about, what their characters are and to what sort of human beings they might hence be best suited. We should be more explicit about the ‘ideal selves’ implied by objects. We should get more skilled at decoding the psychological messages that accompany objects and tag them – so that we might, for example, search websites not by price or brands, but by the psychological identities opeating in a category. If material objects are a language, we need dictionaries to help us to spell out the psychological meanings.

We don’t, it seems, entirely yet understand how the luxury sector works. We think of it in terms of indulgence – and celebrate and condemn it as such. But in truth, whenever we pay somewhat more for the things we use, we’re almost always involved in an act of communicating an intention about ourselves to the world. We’re trying to tell others who we are in the language of things – a crucial civic activity as well as a highly respectable and noble part of being human.