Work • Business Skills

The Collaborative Virtues

Collaborating with other people is hard. Few of us are born knowing how to do it. Odd though it might sound, we have to learn, by conscious reflection, how to work successfully with others. And so we should take care to identify and occasionally nurture what one might term ‘the collaborative virtues’, the set of psychological traits on which good teamwork depends.

1. Modesty about Sanity

It’s desperately easy to settle into the view that it’s always other people’s fault: they are the peculiar, stupid, mean, lazy, judgemental ones. That may well be true, but it doesn’t make progress any easier. We need to start from a different, less self-righteous place. We need to keep clear in our minds all the very many shameful times when we have messed up, lost our tempers, failed to interpret situations correctly and acted vindictively and blindly. We should take on board with good grace the truth that we too are blockheads. Self-righteousness is the enemy of group work.

Part of loosening our grip on self-righteousness means identifying one’s transferences: all the distinctive psychological patterns generated in childhood that one is bringing to situations in the present. We should strive to overcome our flaws through a patient, sympathetic understanding of our psychological histories and the warps they have created in our minds. Self-analysis is – in this context – not self-indulgent, it’s a social virtue. We will become much easier people to be around once we good-naturedly accept that we are all genuinely very difficult – and, in no pejorative sense, a little crazy.

2. Others are Scared, Not Mean or Stupid

When there is conflict, it’s painfully easy to run to the interpretation that those who are giving us trouble are nasty or bad. That isn’t a cheering realisation but it’s an oddly satisfying one nevertheless: it somehow settles our disappointments into safely depressive patterns and confirms an underlying suspicion that the world is peopled by idiots, an imputation for which there is always plenty of evidence.

But the truth is more complicated. Other people are rarely simply bad. What they are far more often is scared. They are behaving in desperately unhelpful ways because they are extremely anxious on some score. Though the raised voices and defensive tone look like signs of strength, no one who is feeling strong ever actually behaves like this. The mature response should hence not be to increase the tension and flare up in return, but to strive to see that one has a hurt, flailing, lost person in front of one, to whom the correct response should be sympathy, calm and understanding. Let’s not always be so shallow as to get put off by the dispiriting externals. Let’s do our colleagues the honour of looking beyond the troublesome surface behaviour, to the frightened person within. It’s an art that every parent knows how to practice with a child in a tantrum and it is no insult to any adult to be treated, occasionally, as if they too were still somewhere inside them very young and deserving of the sympathy we naturally give to children. That’s what tolerance and love really mean – looking beyond the adult bluster to the fearful child within.

© Flickr/Upsilon Andromedae

Strive to be as patient as you would naturally be with him

3. The Art of Directness

Both at a psychological and at a political level, we have backgrounds that have emphasised the art of indirectness.

Only a few generations back, almost all of us lived under deeply authoritarian regimes, where the priorities were keeping quiet and practicing subterfuge. Not speaking directly was a survival mechanism. You wouldn’t tell the king how you really felt: your insights were of no interest to the feudal lord. You learnt to keep very quiet around your tyrannical boss.

Not an understanding ear: King Louis XIV of France

Furthermore, at the psychological level, every childhood is marked by vast differences in status between child and adult which often train us to hide what we experience. We start off as helpless infants exposed to the momentous power of adults. It isn’t easy to find one’s voice with someone who has a 30-year head start, apparently knows everything, controls the TV and computer and has a very strict view of who we are meant to be. The adults are meant to have our best interests at heart, but they may not always provide conditions in which we can freely express our needs without fear of retribution: they do not always offer lessons in the art of directness. Perhaps our caregivers needed us to be preternaturally ‘good’ or were excessively worried by signs of independence. It’s still remarkably rare to grow up in families where saying what you feel is seen as a virtue, rather than a troublesome trait best stamped out with discipline.

And so we become experts in bottling up, in working around people, in not saying what we feel and what is ailing us; or in exploding in rage or settling into sulks rather than confidently letting out our issues in a deliberate, slow, convincing, mature way.

Our silences and defences come not from evil, but from a sense that our voice is illegitimate, because we are – somewhere inside – still serfs or infants. The enemy of good collaboration is an ingrained low self-esteem.

To mature, we need to develop an adequate sense of self-love and resilience: we must feel that we have a right to exist, to be heard and to speak – and that we are strong enough to deal with what might happen if we were honest. We need a sense that we can survive the annoyance of another person. Indirectness is no sin, it’s a natural result of having been forced into patterns of subterfuge through early vulnerability. But we are now adults, people who can survive blows or move on if they prove intolerable. We are no longer cowed five-year-olds, desperate lest an adult withdraw their support. We have options. We can work on improving our impression of our own survivability. We can endure the risk of being disliked – in the name of a cleansing confrontation. We should go through mental exercises to practice inner resilience:

– I may be sacked, but I will find another job.

– They may not like me here, but there will be other places which will respond more favourably.

– What I feel is not always bad or strange: it can deserve to be heard.

We have to tell ourselves helpful, important things that we failed to hear from others sufficiently loudly early on:

– You’re going to be OK, whatever happens next.

– I will love you even if…

Enough of stalking the earth with our shoulders hunched and our eyes wary. We have nothing to be ashamed of. We must channel a voice of confidence at moments when it will be submerged, through tiredness and fear, by the voices of the past.

4. The Weaknesses of Strengths

Other people are often so disappointing, it’s easy to lock on to their faults and simply wonder again and again why they are the way they are. Why are they so slow? Why are they so unreliable? How can they be so bad at confrontation? Why can’t they break bad news? Why are they so shifty? Do they have to be so defensive?

Circling the faults like this has a superficial self-righteous appeal, but it doesn’t begin to address the real issue. There is one giant alternative, a theory we call the Weaknesses of Strengths (WoS for short).

© Flickr/Ludovic Bertron

The theory goes like this: every strength that an individual has necessarily brings with it a weakness of which it is an inherent part. It is impossible to have strengths without weaknesses. Though our minds tend to hive off the strengths and see these as essential, while deeming the weaknesses as a freakish add-on, in truth, the weaknesses are part and parcel of the strengths. We have the wrong picture of what a virtue is; there is no such thing in isolation, it will always be a virtue-vice. So the virtue of thoroughness is always going to bring with, in other contexts, the problem of pedantry; creative brilliance is going to be inseparable from logistical unreliability; people who are fantastic leaders at work are likely to be seriously difficult around domestic chores.

The reason for keeping this in mind is that we often encounter people’s weaknesses at moments when we’re in danger of losing sight of their strengths. At certain points, all it seems we’re bumping into are the weaknesses. We wonder: how did I end up in this relationship, hiring this person, joining this group of colleagues? During tough times, we remember only the flaws. We irritably notice just the pedantic way X chews their food, or Y’s maddening habit of announcing a grand scheme then never following up on it.

We are failing to step back enough and ask the really vital question: not just what are these people’s weaknesses, but what are the strengths of which these pretty annoying traits are the unfortunate shadow sides?

We should remember that there are no ideal candidates out there – and may hence be a little more cautious about walking out on a relationship or calling an end to an employment contract. We may well find people with different strengths, but they will also have a new litany of weaknesses to introduce us to in time.

We have to overcome an unhelpful belief in a theoretical unity of virtues, in the possibility that anyone could be at once loyal and edgy, thorough and fizzing with creative energy; authoritative and pliant. All the virtues cannot coexist – every virtue has a weakness that will negate or contradict other virtues.

This is, incidentally, why people need teams: of 2 or 5 or 100. We need teams because all the virtues don’t coexist and need to be counterbalanced. A team is a union of strengths and a compensation for individual weaknesses. If one could possess all the virtues, there’d simply be no reason ever to live with someone else or join an office. The necessary price for our reliance on strengths is having to endure certain weaknesses too. We haven’t been uniquely cursed.

In the 1870s, when he was living in Paris, the American novelist Henry James became a good friend of the celebrated Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev, who was also living in the city at that time.

Ivan Turgenev: great at writing, appalling at punctuality.

Henry James was particularly taken by the unhurried, tranquil style of the Russian’s storytelling. He obviously took a long time over every sentence, weighing different options, changing, polishing, until – at last – everything was perfect. It was an ambitious, inspiring approach to writing.

But in personal and social life these same virtues could make Turgenev a maddening companion. He’d accept an invitation to lunch; then – the day before – send a note explaining that he would not be able to attend; then another saying how much he looked forward to the occasion. Then he would turn up – two hours late. Arranging anything with him was a nightmare. Yet his social waywardness was really just the same thing that made him so attractive as a writer. It was the same unwillingness to hurry; the same desire to keep the options open until the last moment. This produced marvellous books – and dinner party chaos. In reflecting on Turgenev’s character, Henry James reflected that his Russian friend was exhibiting the ‘weakness of his strength.’

John Singer Sargent, Henry James (1913)

When we’re collaborating we’re often exposed to the downside of people’s positive capacities. Every virtue has an associated weakness. The person who is extremely methodical and can be relied upon to spot tiny (but highly consequential) errors early on is invaluable. They can go through a document with a toothcomb. But maybe to be like that they also have to have a certain dimming of the imagination, a tendency to be less adventurous in conversation and see life mainly in quantitative terms. They might not be your ideal companion on holiday or the person you’d turn to to unburden your troubled soul. But that’s bearable when these are seen as consistent with their valuable strengths.

Not all the virtues can belong together in a single person. The person who is really adventurous around ideas, who doesn’t get intimidated by the power of ‘how we’ve always done things’ – is very unlikely to also be able to have the virtues of modesty and calm. They are quite likely to get carried away at times.

One should be ready for this – and never lose sight of a strength, at moments when the weakness is only too painfully apparent.

Gratitude

Collaboration should be founded on recognition that there are bigger tasks we believe in but cannot accomplish on our own. And not merely in the sense that we don’t have enough time to do it all ourselves. But more profoundly in the sense that we ourselves lack some of the necessary aptitudes and skills for an important project.

There’s a natural temptation of the soloist: we may assume that the most prominent skill is the only one that really counts – and so not much appreciate the less conspicuous contributions of other people – although those background contributions really are necessary, and without them the star efforts would be much less effective.

Gratitude develops in tandem with humility. If you’re ready to admit that you can’t do something well enough (though it does need to be done) then you are developing an appreciation of people who have the relevant ability, even if it is in a less prestigious area than your own. Instead of just envying them – and quietly wishing they would go away or make some big mistake – one is relieved that someone has the needed skill. This kind of gratitude means you don’t necessarily have to like a person to be glad to be working with them.

© Flickr/Government of Alberta

Gratitude involves acknowledging dependence: it means recognising that one really needs the contributions of others. And it can be genuinely frightening to admit that a crucial outcome (which is very important to one’s own ambitions) is significantly in the hands of colleagues. So, the successful collaborator is someone who is able to live with the anxiety of dependence.

Education

A basic reason one gives up on collaboration (or goes through the motions, with limited enthusiasm) is a lack of faith in education, a lack of sincere belief that people can change. You look at your colleagues – at the people you are going to be collaborating with – and just know all the difficulties. That one is so slow, the other one is so narcissistic, a third is so cautious.

The good collaborator isn’t always too worried about this, because they have a theory of change. The fact that their colleagues don’t understand something or have settled into some unfortunate ways doesn’t seem to them like a disaster. The good collaborator has a measure of reasonable faith that better practices and ideas can be made convincing, if introduced with tack and energy. They have faith in the general human capacity to learn (which everyone has exercised to a very great extent at many points in their lives, even if they’ve given up on it at the moment). They are not particularly daunted by the ignorance of others, nor indeed are they dismayed by their own current inabilities. They are believers in education.

Strategic Pessimism

Strategic pessimism is different from despair. It’s a limited, conscious attempt to reign in expectations when these are causing particular difficulties. In reality, we will have to spend time alongside and engaged with people who we find problematic and yet cannot, for a range of reasons, confront honestly and attempt to resolve differences with. Our options can feel desperately limited. We can’t get rid of them, we can’t make them different and we don’t want to just walk out the door ourselves.

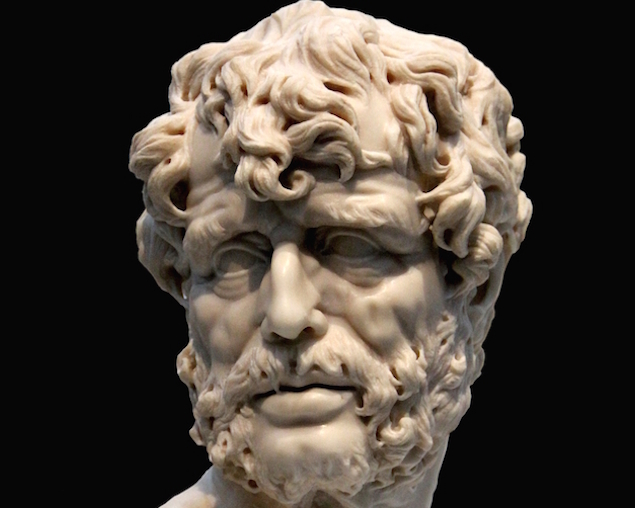

So all that’s left is learning how to live – and interact and collaborate – with people who we don’t intuitively like or who have some marked problems with. Living in a dignified way with things we don’t like but can’t change was one of the central challenges that a group of ancient philosophers – named the Stoics – devoted their lives to exploring.

Stoicism was a philosophy that flourished for some 400 years in Ancient Greece and Rome, gaining widespread support among all classes of society. It had one overwhelming and highly practical ambition: teaching people how to endure.

We still honour this school whenever we call someone ‘stoic’ or plain ‘philosophical’ when fate turns against them: when they lose their keys, are humiliated at work, rejected in love or disgraced in society. Of all philosophies, Stoicism remains perhaps the most immediately relevant and useful for moments of office life.

The Roman Stoic Seneca: the patron saint of challenging meetings.

Contrary to an optimistic mindset that thinks every problem can (with sufficient ingenuity and effort) be put right, the Stoics embraced the idea that there are numerous problems we can’t solve but can nevertheless accommodate ourselves to with grace. They took the view that if we try to solve them, and keep on stoking our hopes that they will get solved and put right, we make ourselves very miserable, because we’re always feeling immensely frustrated.

The Stoics were deeply moved by contemplation of what for them was an everyday sight – a dog being yanked along behind a cart at the end of a rope. The dog is going to have to follow the cart of course: there’s nothing it can do about that; but all the time it fights against the inevitable; it strains and gets agitated and tries to rush off to either side or hold back. It’s an image of immense, but futile, agitation. And it reminded the Stoics of … human beings. From the dog example, they drew an important moral. When the dog gives up trying to follow its own path and simply trots behind the cart, it is much less pained. A key Stoic idea is that we need to make a similar kind of move to live more comfortably with problems that we can’t change in our own lives: we must trot along obediently behind the cart of our difficult colleagues.

The Stoic move is to assume from the start that it is normal and natural for things to go quite badly sometimes. Of course, other people generally are very annoying in some ways. Obviously, collaboration is going to be quite hard. It’s normal to find working with others very difficult.

By presenting problems of collaboration as standard some of the heat is taken out of the situation. We no longer feel that we’re uniquely cursed with insufferable colleagues; we get a little less drawn to the fantasy of how great things might be if only we worked somewhere else.

© Flickr/Kathrin&StefanMarks

Forgiveness

It may not be a term we’re especially used to deploying in the work place. But it signals a crucial shift in attitude. Typically, we are acutely aware of other peoples’ symptoms and are drawn to demonising. We think of the bothersome individual as deliberately being like that, as having on purpose made themselves as they are. We don’t just find them annoying, we blame them. It stokes our resentment. we imagine that at every moment of their existence they have opted to have been self-aggrandising, or lazy, or unwilling to take any responsibility when things go wrong. It’s a way of thinking about them that hardens our resentment.

Forgiveness is tied up with the thought that it’s possible for any decent person to end up in a very unfortunate place. It encourages explanations of how a person who is otherwise quite sensitive, and normally well-intentioned, honourable and decent can end up being defensive, grumpy or sly. We realise that people come to be this way not because they got a strange positive desire to be like that, but because quite bad and difficult things have happened to them, and in response (as a way of surviving) they’ve developed a set of unattractive characteristics.

© Rex/Moviestore

Emma Bovary: How good people can end up doing bad things.

In 19th century France, the idea of a married woman having an affair was regarded – officially and in respectable circles at least – with horror. A fallen woman had no right to sympathy; she must be without any decent feelings. In Madame Bovary, the great-hearted novelist Gustave Flaubert tells the story of how an intelligent, imaginative and serious woman could end up married to one man and in bed with another. He redirects the reader’s response. Emma Bovary is no longer someone to be condemned and treated as an outcast. Flaubert doesn’t pretend that her affair is fine (the novel has a bleak ending). But he does transform the idea of the kind of woman who might end up in this situation.

The feeling that one is oneself troubled or defective in some ways – even if not the same ways as the people who annoy you – is a crucial move towards a measure of forgiveness. It points up the general thought: it’s not just this person. They may be unlike us in the particular way in which they are irritating and difficult – but not in the simple fact of being difficult and irritating: that’s common ground – if only we can bring ourselves to admit it.

The key question is to ask: ‘despite the surface differences, have I ever done anything similar…’: have I ever wished another person to fail, out of spite? Have I ever felt that a task was beneath my dignity? Have I ever wished I could go behind people’s backs and not have to bother with persuading them?’ The point of a forgiving attitude isn’t to say that this kind of conduct is just fine and doesn’t matter. We know it matters. What it does is adjust our view of the person who is misbehaving. It turns them from a demon into someone quite normal, someone a bit like us.

Acceptable Tensions

If we are trying to picture the kind of office where there’s lots of fruitful collaboration going on, we might imagine everyone getting on well; meetings with lots of agreement and shared insights. We tend to associate collaboration with harmony.

But there’s another possibility – one that was most notably explored by the German philosopher Hegel.

In Hegel’s famous book, The Phenomenology of Spirit, he traces the way that the views of ambitious and intelligent people have changed over time. At one point, the most sophisticated and serious people thought that it was extremely important to be devoted to your family and your group. They saw loyalty as one of the most important of human qualities. Then opinion shifted. People came to distrust groups, the idea was that it was most important to be an individual, to find your own voice and develop your own unique point of view.

These outlooks are pretty much diametrically opposed. And Hegel was reluctant to say that one was obviously better than the other. Rather, he suggested they are both ‘true’ – that is each hits upon something important. So, ideally we’d be able to extract the bit of the truth that each side possesses and find a way of holding them together.

Hegel believed that the way in which this happens – in which separated bits of insight get joined together – is not especially peaceful. It’s the good result of conflict. When people conflict well they bring their deepest, most important insights to the surface; by having to defend them against intelligent criticism they find better, more powerful ways of expressing their ideas. Hegel encourages us not to get too alarmed by the clash of ideas. The ideal collaboration – in his view – involves tension, profound disagreements and conflicts in outlook and ambition. Hegel gave good conflict a special name: he called it a ‘dialectic’.

Inspired by Hegel, the dialectical office might incubate divergent micro-cultures. There would be an expectation of squabbling, of opposition and disagreement – in the conviction that, ideally, it is from such tensions that the really valuable insights do finally emerge.

‘Good Enough’ Company

Because commerce really is competitive, and because mistakes are at times harshly punished by the market, work can easily tap into our latent fear of imperfection. We come to feel that we have to get everything right, that any mistake is going to lead to disaster. It’s a feeling that intensifies the anxieties around collaboration. One’s mediocre, awkward or difficult colleagues are surely going to bring the whole business down. The feeling grows that it’s necessary to battle them every day.

The fact is, however, that many imperfect things survive and even flourish in the world. A remarkable number of things can go wrong, and do go wrong, and things muddle along anyhow. The individual and a nation can survive an awful lot of mistakes, perhaps as many as 40% of decisions can go very wrong, and still we’ll get through. There is a number above which things get genuinely dangerous, but it’s perhaps a lot lot higher than we might assume in our more panic stricken moments – as we contemplate the idiocies of politicians or our colleagues. This is what it means to have a resilient attitude: it’s a knowledge that the ship can have a lot of leaks in it and still stay afloat.

Donald Winnicott (1896-1971) was an English paediatrician, who early on in his career became passionate about the then new field of psychoanalysis. He was analysed by James Strachey, who had translated Freud into English, and became Britain’s first medically-trained child psychoanalyst. He worked as a consultant in children’s medicine at the Paddington Green Children’s Hospital in London, and also played a crucial role in public education around child-rearing, delivering some 600 talks on the BBC, tirelessly lecturing around the country and authoring 15 books, among which the bestselling Home is Where We Start From.

Winnicott wanted to help people to be, in his famous formulation, ‘good enough’ parents; not brilliant or perfect ones (as ambitious people naturally might have wished), but just OK.

He was aware that new parents are often very panicked by the slightest mistake. They worry to an extraordinary degree if they miss a feed, or if the child isn’t reading exactly when the books say they should be or if there are quite a lot of tantrums. His tone is always reassuring. He tells his audiences that no one is perfect, all one needs to aim for is to be ‘good enough’, that every child’s upbringing has enormous tensions in it, that a bit of madness belongs to sanity, that feeling lost is a part of finding one’s way – and a dozen more lessons of comparable simplicity and down-beat essential wisdom.

© Flickr/Matteo Bagnoli

The move Winnicott made around parenting wasn’t designed to let sloppy, negligent, indifferent people feel great about themselves. Winnicott was trying to help the normal kind of person who is already quite conscientious and committed but who is in danger of getting very frustrated with themselves and others because they think it’s absolutely essentially to get everything right.

Such worries don’t only exist around the nursery. At work too, we may get so taken up with our ideals that we grow unnecessarily angry and panicked around our colleagues and the normal wear and tear of office life. It is completely normal to want everything to be perfect. But the only long-term solution is to reconcile oneself to the omnipresence of error – and to settle instead on the workable ideal of belonging to a ‘good enough company.’

Find out more about the way the School of Life works with organisations:

https://www.theschooloflife.com/events//