Leisure • Political Theory

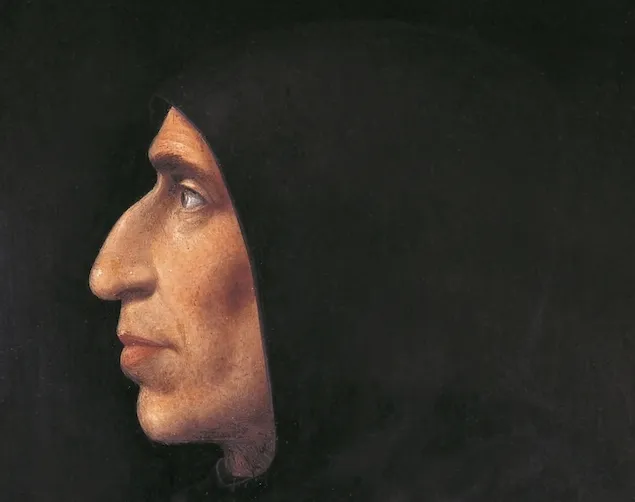

Niccolò Machiavelli

Our assessment of politicians is torn between hope and disappointment. On the one hand, we have an idealistic idea that a politician should be an upright hero, a man or woman who can breathe new moral life into the corrupt workings of the state. However, we are also regularly catapulted into cynicism when we realise the number of backroom deals and the extent of the lying that politicians go in for. We seem torn between our idealistic hopes and our pessimistic fears about the evil underbelly of politics. Surprisingly, the very man who gave his name to the word “Machiavellian,” a word so often used to describe the worst political scheming, can help us understand the dangers of this tired dichotomy. Machiavelli’s writings suggest that we should not be surprised if politicians lie and dissemble, but nor should we think them immoral and simply “bad” for doing so. A good politician – in Machiavelli’s remarkable view – isn’t one who is kind, friendly and honest, it is someone – however occasionally dark and sly they might be – who knows how to defend, enrich and bring honour to the state. Once we understand this basic requirement, we’ll be less disappointed and clearer about what we want our politicians to be.

Niccolò Machiavelli was born in Florence in 1469. His father was a wealthy and influential lawyer, and so Machiavelli received an extensive formal education and got his first job as a secretary for the city, drafting government documents. But soon after his appointment, Florence exploded politically, expelled the Medici family, who had ruled it for sixty years and suffered decades of political instability, as a consequence of which Machiavelli experienced a series of career reversals.

Machiavelli was preoccupied by a fundamental problem in politics: is it possible to be a good politician and a good person at the same time? And he has the courage to face the tragic possibility that, given how the world really is, the answer is no. He doesn’t just think that political advancement comes more easily to the unscrupulous. he gets us to contemplate a darker possibility: that doing rightly and well what a political leader should and fulfilling the proper duties of political leadership is at odds with being a good person.

Machiavelli wrote his most famous work, The Prince (1513), about how to get and keep power and what makes individuals effective leaders. He proposed that the overwhelming responsibility of a good prince is to defend the state from external and internal threats to stable governance. This means he must know how to fight, but more importantly, he must know about reputation and the management of those around him. People should neither think he is soft and easy to disobey, nor should they find him so cruel that he disgusts his society. He should seem unapproachably strict but reasonable. When he turned to the question of whether it was better for a prince to be loved or feared, Machiavelli wrote that while it would theoretically be wonderful for a leader to be both loved and obeyed, he should always err on the side of inspiring terror, for this is what ultimately keeps people in check.

Girolamo Savonarola

Machiavelli’s most radical and distinctive insight was his rejection of Christian virtue as a guide for leaders. Machiavelli’s Christian contemporaries had suggested princes should be merciful, peaceful, generous, and tolerant. They thought that being a good politician, in short, was the same as being a good Christian. But Machiavelli argued differently with energy. He asked his readers to dwell on the incompatibility between Christian ethics and good governance via the case of Girolamo Savonarola. Savonarola was a fervent, idealistic Christian who had wanted to build the city of God on earth in Florence. He had preached against the excesses and tyranny of the Medici government, and had even managed for a few years to lead Florence as a peaceful, democratic, and (relatively) honest state. However, Savonarola’s success could not last, for – in Machiavelli’s view – it was based on the weakness that always attends being ‘good’ in the Christian sense. It was not long before his regime became a threat to the corrupt Pope Alexander, whose henchmen schemed, captured and tortured him, hung and burned him in the centre of Florence. This, in Machiavelli’s eyes, is what inevitably happens to the nice guys in politics. Eventually they will be faced with a problem which cannot be solved by generosity, kindness or decency. Because they will be up against rivals or enemies who do not play by those rules. The unscrupulous will always have a major advantage. It will be impossible to win decently. Yet it is necessary to win in order to keep a society safe.

Rather than follow this unfortunate Christian example, Machiavelli suggested that a leader would do well to make judicious use of what he called, in a deliciously paradoxical phrase, “criminal virtue.” Machiavelli provided some criteria for what constitutes the right occasion for criminal virtue: it must be necessary for the security of the state, it must be done swiftly (often at night), and it should not be repeated too often, lest a reputation for mindless brutality builds up. Machiavelli gave the example of his contemporary Cesare Borgia, whom he much admired as a leader – though he might not have wanted to be his friend. When Cesare conquered the city of Cesena, he ordered one of his mercenaries, Remirro de Orco, to bring order to the region, which Remirro did through swift and brutal ways. Men were beheaded in front of their wives and children, property was seized, traitors were castrated. Cesare then turned on de Orco himself and had him sliced in half and placed in the public square, just to remind the townspeople who the true boss was. But then, as Machiavelli approvingly noted, that was enough bloodshed. Cesare moved on to cut taxes, imported some cheap grain, built a theatre and organised a series of beautiful festivals to keep people from dwelling on unfortunate memories.

Giuseppe Lorenzo Gatteri, Cesare Borgia leaving the Vatican

The Catholic Church banned Machiavelli’s works for 200 years because of the force with which he had argued that being a good Christian was incompatible with being a good leader. But even for atheists and those of us who are not politicians, Machiavelli’s insights are important. He writes that we cannot be good at or for all things. We must pick which fields we want to excel in, and let the others pass—not only because of our limited abilities and resources, but also because of the conflicts within moral codes. Some of the fields we choose—if not being a prince, then perhaps business or family life or other forms of loyalty and responsibility—may require what we evasively call “difficult decisions”, by which we really mean ethical trade-offs. We may have to sacrifice our ideal visions of kindness for the sake of practical effectiveness. We may have to lie in order to keep a relationship afloat. We may have to ignore the feelings of the workforce in order to keep a business going.. That – insists Machiavelli – is the price of dealing with the world as it is, and not as we feel it should be. The world has continued to love and hate Machiavelli in equal measure for insisting on this uncomfortable truth.

Machiavelli is prey to a natural misunderstanding. It can sound as if he is on the side of thuggish or slightly brutal people; that he’s cheering on those who are mean or callous. But actually his stern advice – about being ruthless – is best directed to those who run the risk of losing what they really care about because at key moments they are not ruthless enough.