Work • Good Work

When Are We Truly Productive?

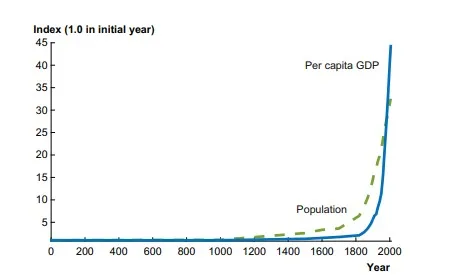

In the last two hundred, the world has witnessed the greatest increase in productivity in the history of humanity. From 1 A.D to 1820, living standards in the West slowly doubled, rising from a GDP per person of $600 a year to $1,200. Then, over the next 200 years, it catapulted up by a factor of more than twenty, to stand at over $26,000.

Not only have we become more productive, we have also acquired a sense of what being productive should look like: being in an office, surrounded by a lot of people, attending meetings, travelling a lot and answering many, many messages.

But we may thereby be in danger of missing out on what the most fruitful kind of work actually requires. In so far as the world most decisively advances through ideas, through clarity of thought around the large first order questions, then arguably some of our most productive moments will have little in common with the scenarios envisaged by the modern religion of hard work. They will be quiet, outwardly idle moments in which we’ll at last have the opportunity to break through cliched assumptions and received ideas, in which something vital and authentic will surge through our minds and in which we’ll have the courage to take a neglected intuition seriously or give an opposing point of view the benefit of the doubt, moments in which we’ll realise how little time we have left on earth and will use the feeling of panic to orient us towards what we really want and have known for a long time already needs to be done.

Paradoxically, it can be hard to do this sort of thinking in the expected locations. Familiar places breed familiar thoughts. Surrounded by a hundred colleagues, an original vision can feel inappropriate. Thinking is also hard when thinking is all we’re meant to be doing. A blank sheet of paper on a brisk Monday morning can panic the mind into silence. The best sort of thinking emerges when we have no set agenda, in the hollows of the day, when we are meant merely to be walking around the park or taking a train journey, having a bath or staring blankly into space. It is then that our best, but also most furtive thoughts, may be lured out of the unconscious and can be glimpsed by reason before they have a chance to run away again. There is a discomfiting aspect to many of our important ideas; they would, if taken seriously, often entail an element of disruption. We might have to make big changes to the way we do things, we might have to upset people and correct now false assumptions. Which doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t take such thoughts seriously, but it explains our deep temptation not to. We are so much better at executing on plans than stepping back to evaluate whether the plans are the right ones. We are geniuses at working out the thousand small steps required to advance a project, but poor at giving ourselves the time and space to figure out whether the project was ever even relevant.

If we had the strength to disagree with the harried conditions of modern work, we might come to recognise that a quiet room in mid afternoon, when we have nothing pressing to do till supper, no one to see and no messages to reply to, might be among the most productive places we could be. We would recognise the profound value of spending hours staring out of the window, ostensibly ‘wasting time’ but in reality perhaps generating thoughts that would spare us extraordinary confusion and error. The figure in Vilhelm Hammershøi’s painting might look as if she was doing ‘nothing’, but some of our greatest insights come when we stop trying to be purposeful and instead respect the creative potential of reverie and free association. Window daydreaming is a strategic rebellion against the excessive demands of immediate (but ultimately insignificant) pressures – in favour of the slow development of more substantial plans.

Vilhelm Hammershøi, Interior, Strandgade 30.,1909.

We are encouraged to be hard on ourselves for our ‘lazy’ moods, inactivity can feel like a sin against the bustling activity of modernity. But it might be that at points the real threat to our happiness and self-development lies not in our failure to be busy, but in the very opposite scenario: in our inability to be ‘lazy’ enough. Outwardly idling does not have to mean that we are neglecting to be fruitful. It may look to the world as if we are accomplishing nothing at all but, below the surface, a lot may be going on that’s both important and in its own way very arduous. When we’re busy with routines and administration, we’re focused on those elements that sit at the front of our minds: we’re executing plans rather than reflecting on their value and ultimate purpose. But it is to the deeper, less accessible zones of our inner lives that we have to turn in order to understand the foundations of our problems and arrive at decisions and conclusions that can govern our overall path. Yet these only emerge – tentatively – when we are feeling brave enough to distance ourselves from immediate demands; when we can stare at clouds and follow the movement of tree branches.

Someone who looks extremely active, whose diary is always filled, may appear the opposite of lazy. But secretly, there may be a lot of avoidance going on beneath the outward frenzy. Busy people evade a different order of undertaking. They are practically a hive of activity, yet they don’t get round to working out their real feelings about their work. They constantly delay the investigation of their own direction. They are lazy when it comes to understanding the purpose of their lives. Their busy-ness is in fact a subtle but powerful form of distraction – in fact, a kind of laziness.

Our lives might be a lot more balanced if we learnt to re-allocate prestige. We should think that there is courage not just in travelling the world, but also in daring to sit at home with our thoughts, risking encounters with certain anxiety-inducing or melancholy but also highly necessary ideas. The heroically hard worker isn’t necessarily the one in the business lounge of the international airport, it might be the person gazing without expression out of the window, and occasionally writing down one or two ideas on a pad of paper. That might be the hard work that will properly honour our potential.