What Optical Illusions Teach Us About Our Minds

Psychologists have long taken a certain glee in pointing out small but telling flaws in the way that we read the world. Though for the most part our senses give us extremely accurate pictures of what is going on around us, there are some intriguing situations in which we observe the gap between reality and our subjective impressions of it; situations where our senses fail us in subtle ways. For example, we make basic errors when judging sizes of two identical lines depending on the direction of arrows placed at the end of them:

Or we’ll keep seeing lines as crooked that are — in fact — entirely straight, depending on the arrangement of black tiles between them.

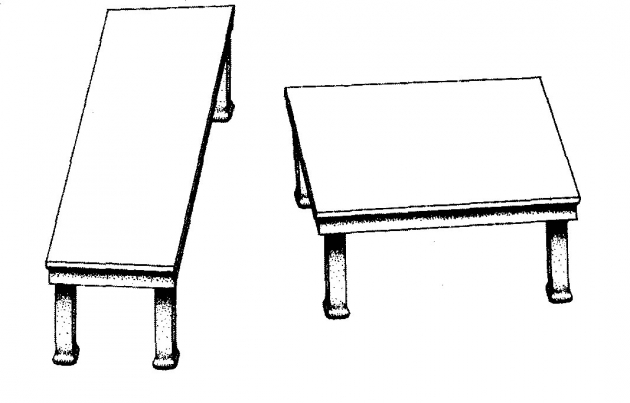

Or show us two grey shapes of identical sizes with legs on them, one vertically aligned, the other horizontally, we won’t be able to believe that the shapes are — in fact — of exactly the same dimensions. Our eyes keep telling us that the grey shape on the right is shorter and more squat and that the one on the left is tall and thin; but get your scissors out, and the truth of their identical natures will be incontrovertible.

Such optical illusions are humbling — and somewhat funny — because they demonstrate that, despite our immense competence in many areas, our mighty minds can be fooled in relatively simple ways. We are not quite as in control as we imagine.

However interesting this might be in the visual field, the relevance of the idea extends far beyond this. It is when it comes to our reading of psychological reality that our proclivity to illusion becomes truly consequential and important to adjust ourselves to.

Our assessments of people and emotions are riddled with quiet errors. For example, we repeatedly get in a muddle about how much danger we are in. Or who loves us and who doesn’t. Or where we should place our trust. Or who would be a good partner. Or where anxiety is required and where calm would be more fitting. The person we have decided to befriend might be a scoundrel. There may be love when we imagine there isn’t any. There should be calm when we insist there is danger.

Our perceptual errors in the psychological field tend to have poignant origins: we can’t see straight because of the way we were brought up. Like trained animals, it’s the early years that determine how we assess what is around us. And — sometimes — like an ill-handled cat or horse, we get things very wrong. We start to shriek every time a bell rings; we keep expecting disaster when none is on the cards; we keep not believing in kindness when we should let ourselves go; we keep imagining we have to jump through certain hoops when there is no requirement we do so.

The best way to deal with our tendency to psychological illusion is to know that it afflicts us. Rather than blithely assuming that everything we feel is true, we should — as good post-illusionists — give ourselves a wide margin to absorb our tendencies to error. We should take our time before judging situations, we should know that at certain moments — especially when we are frightened or tired — we won’t be able to ‘see’ what is really going on in front of us and should probably lean on the judgement of a calmer friend. We should take a second, a third and a fourth look at situations — and be ready to disbelieve a lot of what we might at first sight have been absolutely convinced of.

It isn’t any sort of insult to our minds to recognise that they do not — however much we’d love them to — always work properly. We start to become better judges of reality when we can dare to acknowledge how wrongly we are prone to see many things. What we think is there may not be there at all. Our worries may be misplaced; our fears angled in the wrong direction; our love pointing us to erroneous candidates. We should be kind towards our minds; they are doing their very best to see what is there. But, we can say with love, they may very often be getting subtly rather wrong.