Self-Knowledge • Growth & Maturity

The Futility of Seeking Closure

One of our most powerful longings, in relationships where we have suffered (by which we chiefly mean relationships with our parents and our lovers), is for something we colloquially call ‘closure’. We may not always consciously know why closure is important, but we feel its absence keenly.

In the fantasy of closure, long after certain wounds have been inflicted, we imagine being able to sit down with a parent or an ex. It might have been months or decades since the difficult times. We will, in many ways, have moved on. We might be a high-earning executive at an important corporation. We might be in love with a beautiful and kind new partner, with whom we have plans to start a family. Nevertheless, something in us continues to feel responsible for an earlier version of ourselves: a little boy or girl who was roughly handled, who got shouted at repeatedly, who was humiliated and mocked. Or for a loving side of us that had to suffer the indignity of an affair, that had to watch their then-beloved partner slide away evasively and mysteriously, that wrote a succession of long letters that went unanswered.

Why Closure Is Important – and Why It So Often Eludes Us

That’s why we have called for a meeting with a now elderly parent who arrives with a walking stick – or for a tea with our ex who greets us warmly in a new bright-blue outfit. The fantasy might go something like this: ‘I felt from the first moment as if you favourited my sister; nothing I did was right. Why were there two rules in our family? One for me, and one for her …’

And the parent, who has thought about this at depth, who has spent hours reflecting on their role, who has ached to make amends, will say: ‘Darling, I know how much this has hurt you. I’ve tried so hard in recent years to make it up to you. I know you resent me fiercely still. What matters is to say how much I love you and how sorry I am for the pain this caused you …’ They might go on to give a backstory to their cruelty. They behaved like this because of their relationship with their own mother. They know why they were imperfect. They’re accountable. They understand themselves. They’re extremely sad about it all.

Likewise, the dream is that the ex-partner will have shown up with a raft of insights. They will have gone to therapy and benefited. They’ll have used the months since the parting to put together the pieces: ‘I didn’t dare to explain that I wanted a new start. I felt grateful to you but also so guilty. It’s from this that the affair came. It’s not excusable – you’ve every right to be furious with me …’

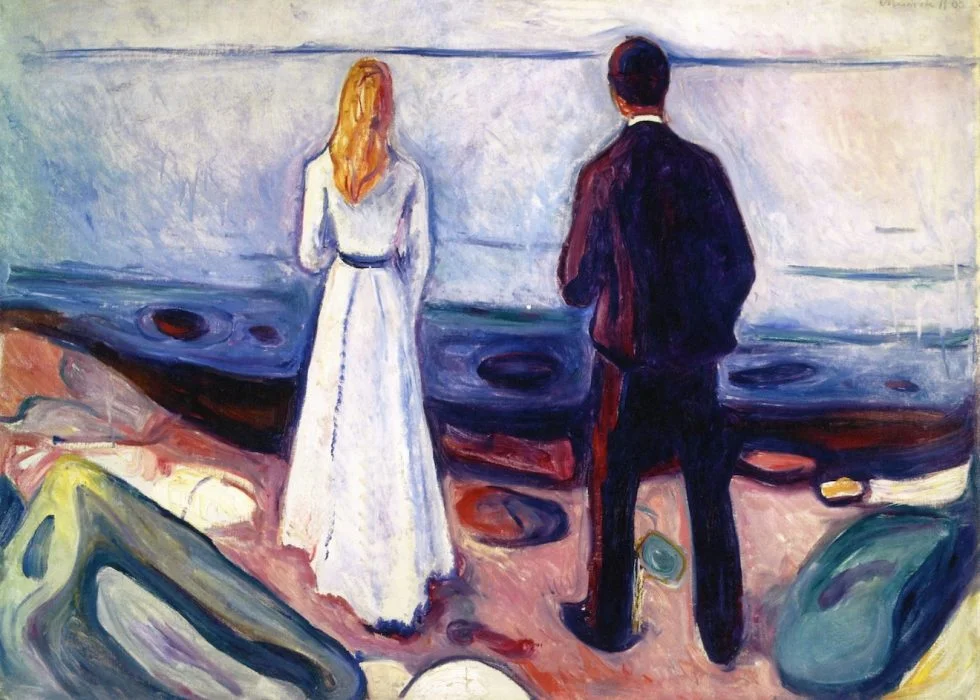

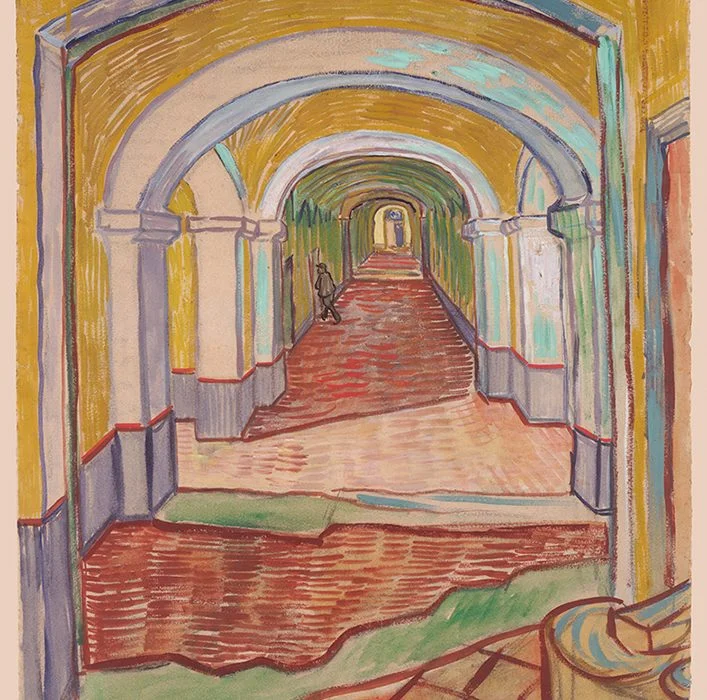

But though such poignant moments must exist – though there have, in the history of the planet, undoubtedly been such scenes by pyramids and waterfalls, in temple gardens and colonnaded arcades – we can confidently, quietly insist that they have always been the exceptions.

Far more common is ongoing dislocation and mystery: the parent who flares up, ‘How do you mean? Why can’t you be more grateful? Yet more moaning, I suppose.’ Or the lover who denies everything or vanishes into a sentimental fog: ‘I’m sorry, I can’t think very clearly. I’m sure you’re right. I must be going …’

We can come away with a dictum: if they were damaged enough to hurt us as they did, they won’t have the wherewithal to heal us as we hope. No one who could crush a five-year-old child or rebuff a caring partner will plausibly be able to turn around in years or decades and make it right. One either has the capacity for kindness and maturity – or one doesn’t. One either has tendencies to sadism – or one doesn’t.

This is not to say that we should stop seeking closure; only that we should stop seeking it from the very people who made it necessary.

Finding Healing in Unexpected Places

We need to take our longings to other, more effective figures: to wise therapists, to kind friends, to new partners, to substitute parents. These will be the ones who will explain, who will set pain in context, who will replenish our reserves of hope. In learning why closure is important, we also begin to understand that its source is rarely those who wounded us. There are people who can right our wrongs; they are just very seldom the confused, unformed people who actually wronged us.