Leisure • Art/Architecture

What Love Looks Like

If we think about what love might look like in a work of art, certain stock images tend to come to mind: a couple kissing on a bridge, a wistful soul gazing out to sea at dusk, two hands interlaced …

But in a true ideal museum of love, one work would deserve a central place – even though it seems, at first glance, to have nothing whatsoever to do with love.

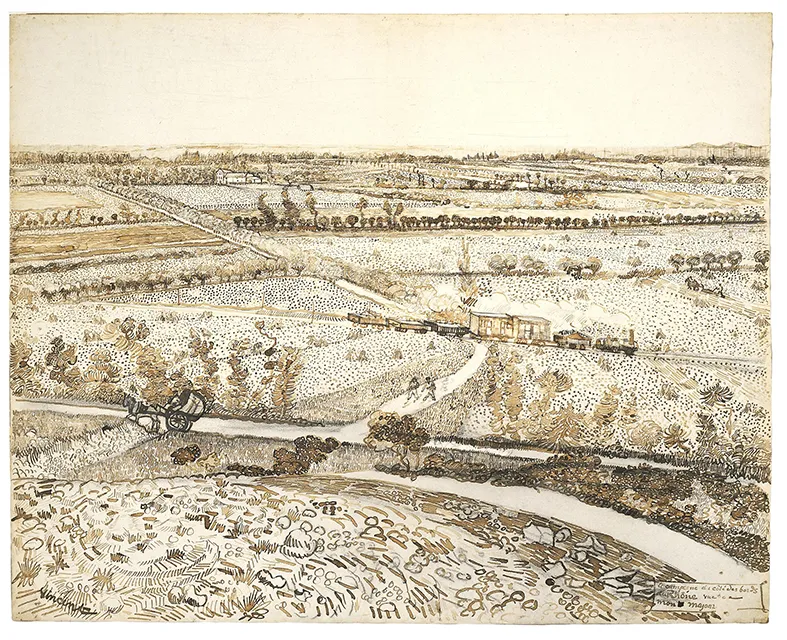

Vincent Van Gogh completed it in a few days in the summer of 1888. Drawn in ink reinforced with pencil on a sheet of brown paper, it depicts a flat stretch of the southern French countryside, near the city of Arles, where Van Gogh was living.

A depiction of a landscape, it is simultaneously a testament to an act of uncommonly concentrated attention – an essay on rare and patient noticing. Where we might have been tempted to hurry by, Van Gogh has remained fixed and registered everything: a small figure ploughing a field, two men walking down a path, a local train – some of whose carriages are carrying goods, others passengers – crossing in the middle distance, and then the earth, always the earth, in its manifold varieties: wheat stubble, trampled grass, loose and tilled soil – each difference marked by the artist’s careful, rhythmic hatchings and cross-hatchings. Humanity emerges as a modest, touching species, making its indentations on a vast world beneath an ordinary sun.

There is no overt moral, no apparent ‘message’. It is, at one level, just a ‘view’ – and yet it might bring tears to our eyes. For what Van Gogh is doing is correcting our ordinary inattention and haste, pulling against our usual sadness and self-hatred, and calling out for renewed care and sympathy. This is looking as a god might at its creation, or a parent at their child – holding in mind the shape of a young one’s fingers, their lips as they articulate a word, a lock of their hair. ‘A bit of countryside’ has been translated – under this supremely generous artist’s gaze – into a phenomenon worthy of infinite regard; the difference between ‘a child’ and ‘your child’, ‘a person’ and ‘your partner’, ‘a stranger’ and ‘a loved one’.

Van Gogh is modelling for us a care that is, in the end, deeply transferable – one that can shift from the trees and fields of southern France to life more broadly, to a level of sympathy and appreciation we know we owe to one another, and would give, if only we were not so often burdened and afraid. We are being gently goaded to live with greater awareness and charity, to turn our reflex guardedness and solemnity into something less defended and more tender. We may think we have been shown a view. But we turn away and learn – once again – to notice one another.