Self-Knowledge • Emotional Skills

What Is Gut Instinct – and How to Access It

One of the odder features of our psychology is the existence of what we colloquially call our ‘gut instinct’, a faculty that throws up a sense of how things are, that sits to one side of our usual conscious impressions. Our gut may, for example, give us a powerful notion that a particular person is very right for us – or, indeed, that they are distinctly wrong. Our gut may have a view on what job we should be doing, which home we should buy or whether or not we should ask someone a question. What marks out this instinct is precisely that it is an instinct – as opposed to a reasoned proposal whose premises we can explore, probe or explain to someone else. We cannot account for our gut feelings; we don’t know why we feel as we do – we are simply, vaguely yet strongly, certain that we do.

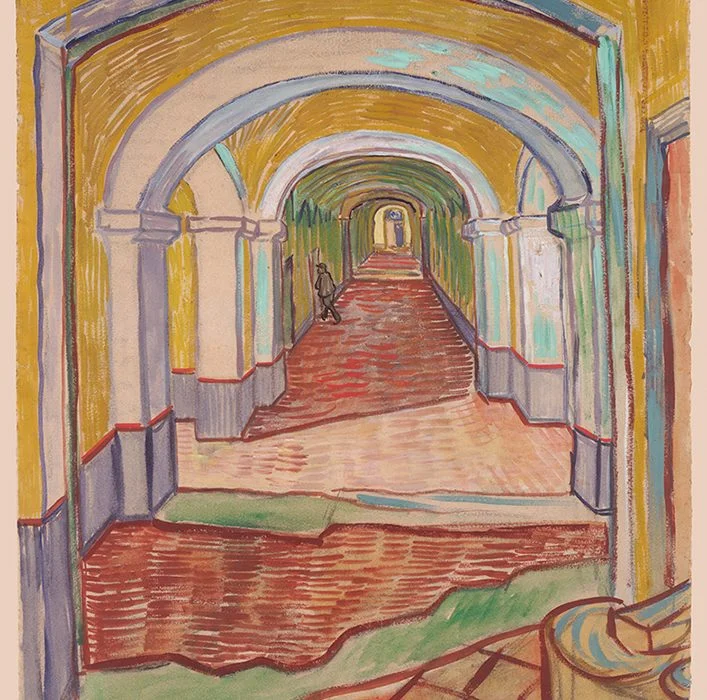

It can be tempting to dismiss this mute and mysterious point of view. We aren’t used to surrendering to forces we don’t understand and that can’t justify themselves in language. And yet, after a certain amount time on the planet, we may find that we have run into a sufficient number of situations where we ignored our gut instinct, and paid a heavy price for our neglect. After the breakup of a relationship or the end of a business venture, we might, for example, ruefully tell ourselves: ‘I should have trusted my gut …’ A part of us, to which we paid insufficient attention, appears to have known that there was a problem right from the start. Our reason took the upper hand – and we suffered as a result.

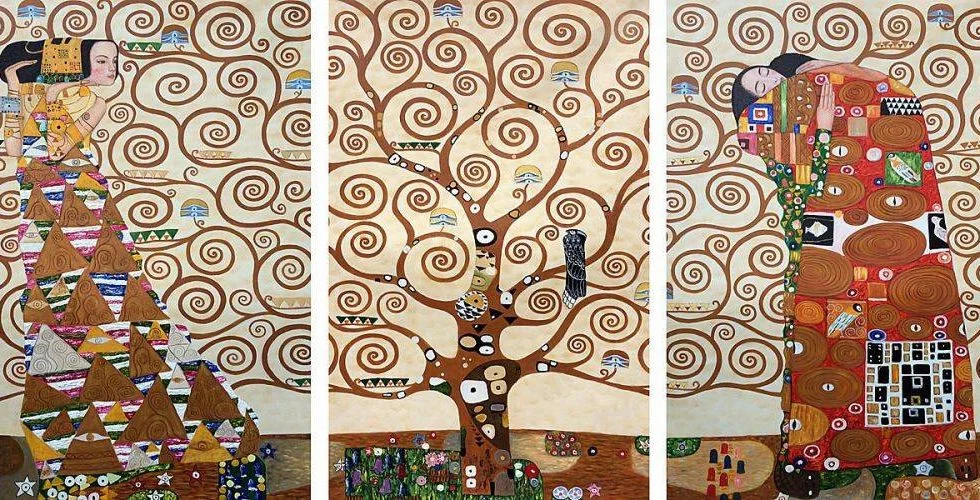

What then is this gut instinct? We could define it as a conclusion that flows from an accumulated wisdom that resides in us but isn’t consciously accessible to us. When our gut tells us that someone is ‘wrong’, what’s occurring is that all our knowledge of human beings –built up inside us since birth – is being marshalled in an instant. Under pressure to respond swiftly, it surges into our minds as a distinct perspective. Dozens, even hundreds, of tiny details are noted at lightning speed and processed by a part of our minds to which we have no more access than we do to the part of us that knows how to walk or ride a bicycle or use the pluperfect. It delivers an answer long before our conscious minds – slow, lumbering instruments – are in any position to say why. The gut is a part of our brilliant minds working so fast (normally in response to a pressing need for answers) that we, the conscious part of ourselves, aren’t let into the steps taken to get to a position. The mind is privileging the answer over the route to it. We’re allowing ourselves to be as clever as we are, at the cost of not being able to spell out how we got there.

If our gut instinct is often superior to our conscious logic, it is because it seems able to bypass certain biases that lead the latter astray.

Reason is prone to respond naively to other people. It assumes that because someone calls themselves our friend or partner, they will be inherently good. Our gut can keep in mind a more complex and darker truth: there can be betrayal even in intimate situations.

Reason is inclined to be too much on the side of how things should be: that mothers are kind, that children are loyal, that partners don’t steal. It is invested in finding the world as sane and healthy as it wants it to be. The gut has less investment in upholding certain notions of propriety: that one’s own parent might be good, that a friend is trustworthy… The gut is less interested in sunk cost: it doesn’t insist that a certain job is fine just because we’ve spent eight years training for it. The gut can be more appropriately ambitious. It doesn’t need us to be meek or make ourselves small to accommodate the egos of others. It can tell us to follow opportunities that the reasoning parts of us are daunted by.

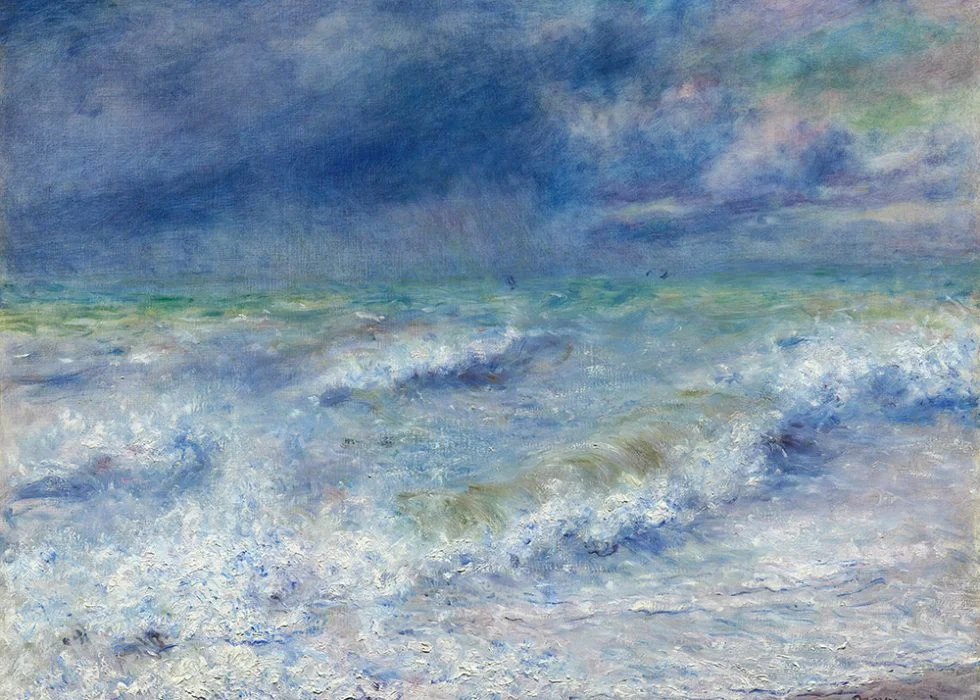

The gut locks onto small cues. It knows that great truths may travel towards us in apparently minor details, that a central fact about someone may be carried in the way their eyes move or what they are doing with their hands. It listens not only to what someone is saying; it’s highly alert also to their posture, their smell, the way they sigh – details that the rational mind is unfairly prone to dismiss as ‘petty’ and an unreliable basis on which to form large judgements. The gut seems primed to notice incongruities. It doesn’t pay attention to large statements (‘I love you …’). It’s alive to almost negligible omissions from the wider story (how long someone is taking to write back, the way they responded when the taxi was delayed …). Most of all, because the gut doesn’t require proof in the ordinary sense, because it doesn’t have to operate with arguments, it can move almost instantly. It can be days, weeks, years ahead of the conscious mind. It’s mining insights we’ve forgotten we even had; it’s drawing on the experience of our entire lives, when reason can keep in view only the tiny amount of data it would be able to pass an exam on. It knows before we know. It just can’t say why.

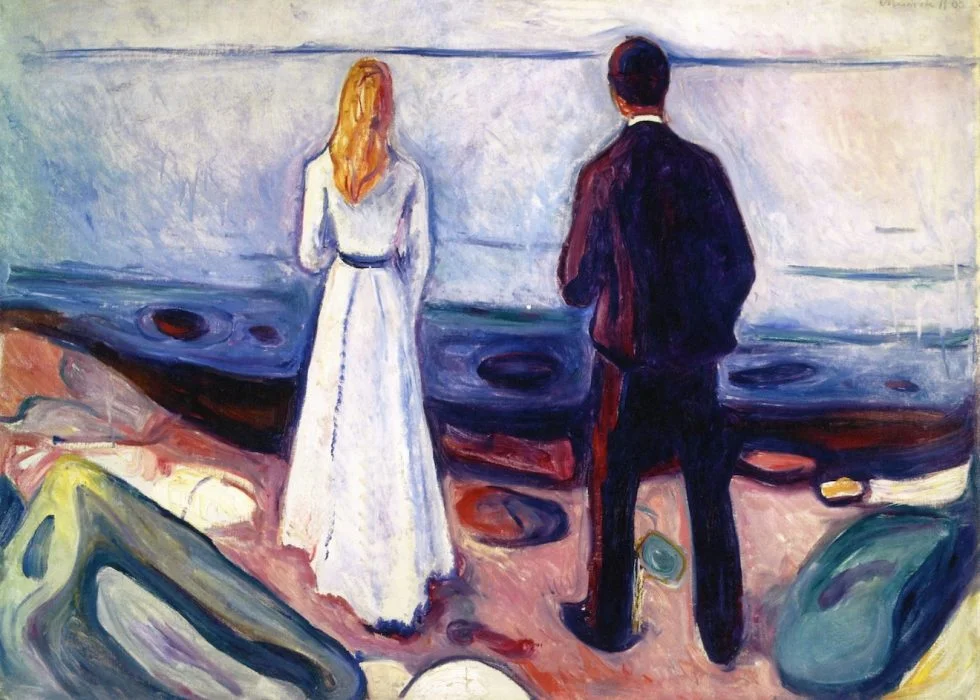

Part of our problem with our gut instinct is that it has low prestige as a method of exploration. Schools and universities aren’t interested in it. Serious people seldom speak of it. As a result, we don’t take enough time to listen to it and can end up unsure how even to do so. Accessing it requires a slightly artificial manoeuvre, one that can sound both simplistic and slightly mystical. We need to pause our ordinary activities, still the outer world, and ask ourselves a basic-sounding question: What do I feel is really going on here? What is my gut telling me? And, surprisingly, there will almost always be an answer waiting for us: Leave them. Or: Don’t leave them. Trust or don’t trust. Be patient or you’ve waited long enough. A part of us has already mapped out the path we need to take ahead of the rest of us.

None of this is to say that our gut is invariably correct, that it represents an unfailing set of truths. This would be as flawed as privileging our reason exclusively. There are – we need to admit – instances when our gut gets it wrong too (no, they weren’t good for us; no, we shouldn’t have left the relationship; no, the house wasn’t properly built, etc.). It may in the end be as foolish to always listen to our gut as never to listen to it. We should think of it as an auxiliary kind of intelligence which we should more often consult but never entirely trust either. When dilemmas grow especially intense, we should learn to juggle our two brains – the gut and the reasoning faculties – to give ourselves the very best chance of making our way to the complex and elusive truths we need to live by.