Self-Knowledge • Behaviours

The Theory of Triangulation

‘Triangulation’ is a term used in psychoanalysis to refer to the way in which someone can be drawn to repeatedly introduce a third party into their two-person relationships, in order to reduce the risks that they unconsciously associate with singular dependence.

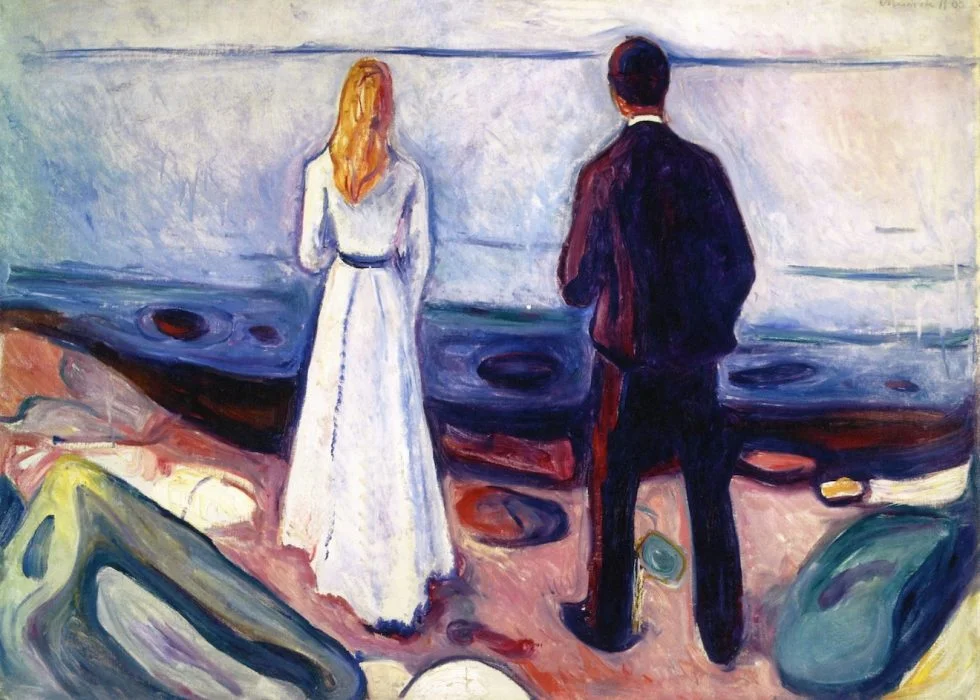

This theory posits that the ability to sustain a happy two-person relationship is never a given. It is reliant on a privileged emotional history; it is the fruit of a warm, sustained early dyadic relationship with a kindly and attuned parent or a caregiver. We will tolerate – and delight in – coupledom, if and only if, towards the start of our lives, we had an experience of focused devotion from another person: someone who held us tightly in mind, spent time with us and lent us the feeling that we satisfied them. Perhaps we were in the kitchen with them, neither of us talking much. They might have been busy with work while we sat in the corner with some bricks, but we knew they were there if we needed them, and we sensed how richly we existed in their imagination. We were their poppet, or their little monster, and it felt sweet – and more than enough. From this, we were able to draw a vital moral with a lifelong resonance: I can sustain another person’s attention, they won’t turn on me, two is sufficient, it can be safe, I don’t always have to look elsewhere, I can rely on someone, being in a couple can satisfy my needs.

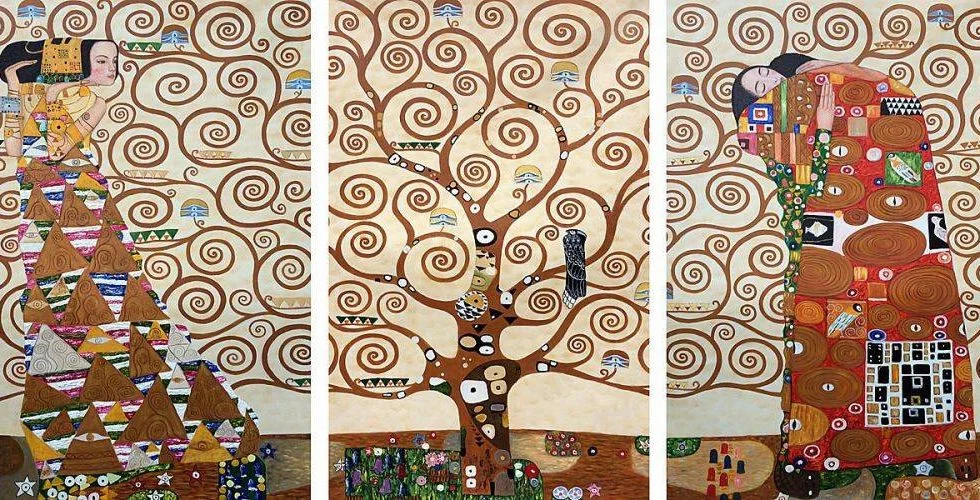

It is no surprise that one of the most popular of all genres of painting in the Western tradition celebrates precisely these possibilities and pleasures: again and again, we see a mother and child depicted, satisfied in each other’s presence, wanting no others, cosy and at peace, while outside (in many works) the kingdom goes about its business and knights ride on horseback across a delicately delineated landscape. We project onto Mary and Jesus what we have all so badly wanted for ourselves.

Sadly, many of us have not been very fortunate in our search for dyadic experiences. Perhaps a parent was never there, or we felt that their most intense love was for a sibling. Maybe we had an impression that they were rivalrous and didn’t quite wish the best for us (they might have been prone to rage or sarcasm), or we felt that we had disappointed them in some fundamental way (we might have been born the wrong gender for them, or we didn’t like their chosen hobbies). From these crushing experiences, we derived another, less salutary moral: be careful never to depend on just one other person; love is highly exposing and threatening; men and women are a disappointment; spread out your allegiances to mitigate the agonies of forthcoming betrayals.

As a result, in adulthood, we may feel ineluctably drawn to weakening all two-person bonds. We may find ourselves flirting with others just as a relationship (in which we ostensibly believe) is starting to strengthen. An affair – whether imagined or real – becomes a necessary escape from the subterranean terrors of successful love.

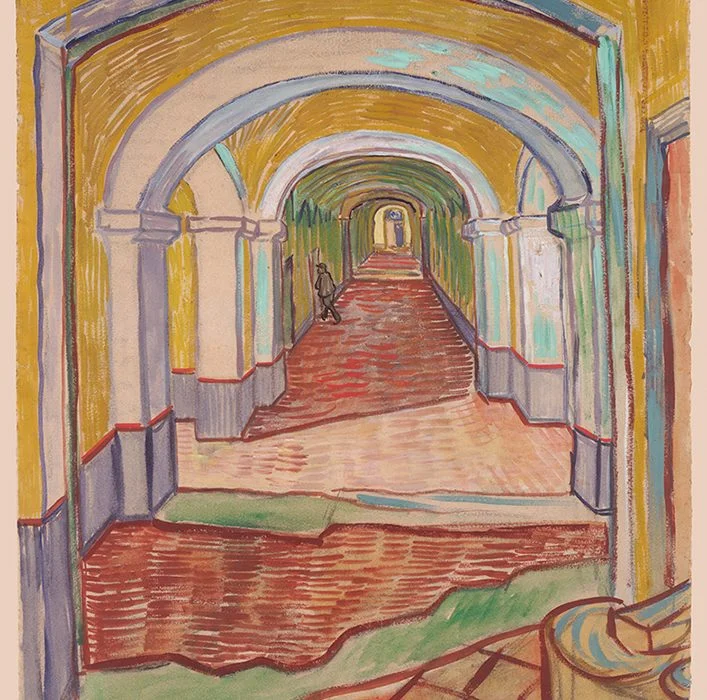

But triangulation can take other, less obvious and less individuated forms. A ‘third’ can be anything that breaks the bond between the two partners. It could, for example, be a mobile phone that keeps cropping up between the pair and has to be consulted whenever the conversation grows too intense or meaningful. It might be a group of friends who continually have to be pulled in for meals, parties and holidays to ensure that closeness can be shattered and distance maintained (they may need to be contacted for their views in the middle of dinner or during a shopping trip). The third could be an obsession that removes a person from any chance of dialogue for long periods: a persistent worry about their reputation, anxiety about their appearance, an obsessive rivalry with a sibling, or a paranoia about something they might have done a decade before. The third could even be a therapist whom one member of a couple again and again uses to relativise their partner’s insights and perspectives: ‘Interesting you should think that – Ricardo thinks it’s actually about your mother …’ or ‘Kathryn wonders why I always have to ask you for your opinion …’

We should be generous with ourselves for our triangulating tendencies. We have them not because we are bad, but because we have suffered and because we were disappointed and terrified at an extremely vulnerable stage in our development. We might, with great kindness, try to explore our stance:

— How do I feel about dyads?

— To what extent am I tempted by a third?

— What are my thirds of choice?

— What might have gone awry in my early experience of couples?

At the same time, if we find ourselves in a relationship where the other person keeps finding ways to be elsewhere, we might learn to give a new, more encompassing name to their flights: we can say that behind the friends who keep being invited, the phone that is always drawn out, or the therapist who is wielded as a rivalrous source of authority, lies the pattern of triangulation.

With a deeper understanding of the concept, we may come to appreciate – perhaps as never before – what an extraordinary achievement of psychology and love it is to feel, at certain precious moments, as if two might very much be enough.