Self-Knowledge • Fear & Insecurity

Dating, Confidence and Childhood

We tend to keep a wide intellectual berth between our childhoods and our dating lives. The first was about rubber rings, seaside holidays, sponge cake, Granny, nounou and so on. The second might be about chic West End restaurants, rooftop bars, late-night playful chats on dating apps and trips into the darkness in bold new outfits.

Yet it may be that the two fields are deeply intertwined, and that the clue to the success of the latter lies – fundamentally – in the progress of the former. To understand how to feel worthy of love, we may need to return to childhood.

There is one question in particular we might ask ourselves around dating that gives us direct access to the emotional structure of our pasts. The question is simply: How lucky do you feel someone would be – in the abstract – to be your partner?

Here, for some of us, there might be an immediate concern: what if, in answering, we were to commit the sin of arrogance? What if, for a moment, we thought that someone might be very lucky indeed – but thereby got ahead of ourselves? What if we believed we had some value, but were seen to think so by others, and humiliated and mocked as a result?

We might become aware of an inner censor, constantly policing our ideas for signs of excessive pride. This censor associates safety and sanity with not thinking ourselves too attractive, with not believing too firmly in our own worth. It has built a bridge between survival and not trusting that we are anything very special at all.

The censor may have been active for such a long time, we hardly notice it, just as English people hardly notice the rain. It is simply the background we are used to. We may be melancholy as a result; we aren’t surprised, or even particularly aware.

Reclaiming Our Own Side

But imagine if – right now – we were to make this the focus of some serious remedial effort. What if we were to say (quietly in our minds): enough of thinking ill of ourselves. Enough of always giving our opponents the benefit of the doubt. Enough of associating safety with meekness. We might be slightly marvellous. We might be a real asset to someone else’s life. They’d be lucky to have us – very lucky indeed! And if they didn’t want us, too bad for them: absolutely their loss.

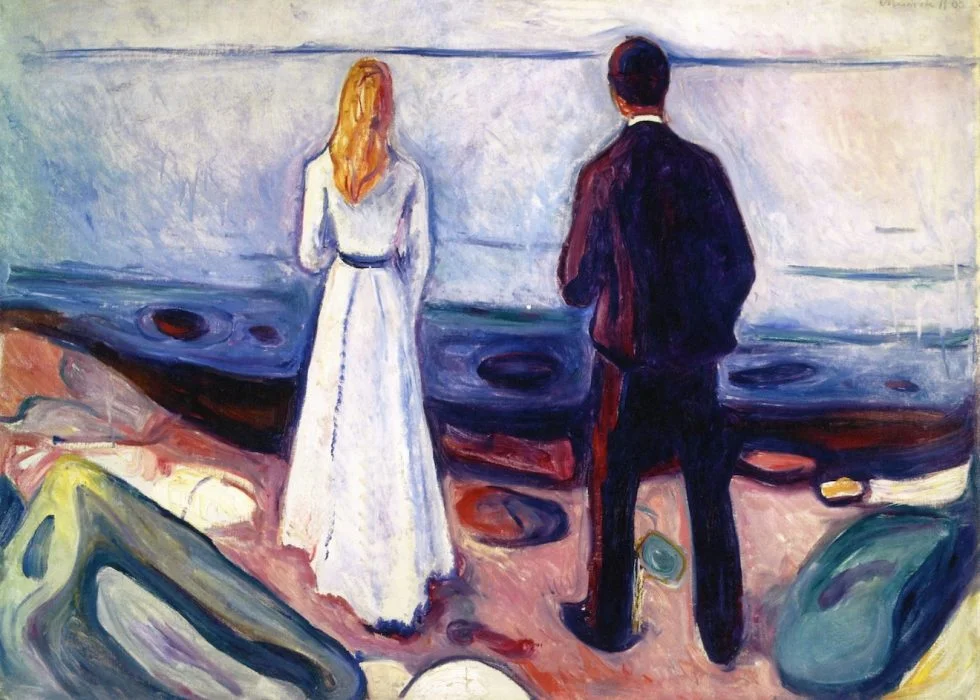

What if – first as a thought experiment, and eventually as a reality – we were to come firmly over to our own side, in the way a fiercely loyal mother (the sort we almost certainly didn’t have) might, as she hugs her child to her, strokes their fine locks of hair and calls them her angel?

We may be used to mocking mama’s boys or girls – as we mock many things we secretly wish we could have been. But how delightful, and how utterly mature and solid, such people grow up to be. They aren’t the ones suffering from depression; they don’t need to visit psychiatrists; they aren’t bawling their eyes out in the early morning, wondering where they went wrong. They possess all the solidity of those who have, for a very long time, been incubated in love, who can bear themselves because they never forget that they have been the objects of generosity and tenderness from zero to eleven.

The Real Inequality: How to Feel Worthy of Love

Life is roughly the same length for most of us. What is not equal is how cheerful people are with themselves as they journey through it. There is such wide variation, and it is everything. We speak a lot about inequality, and much of politics wants to correct it. But the injustice that really needs fixing is the one between those who possess self-belief and those who do not (because it was stolen from them early on).

Look at those people eating on their own in the restaurant – feeling utterly content as they ask the waiter for a bit more mustard, because it matters how tasty their meal is. And look at those others, more deprived, more furtive, who walk through the world with a hounded look, who barely dare to ask where the toilet is, who go hungry rather than eat anywhere alone, who could never ask for mustard or gravy or a doctor, who are ashamed of their own reflection and who, because of all this – very sadly – head straight into relationships with people who show them all the contempt they secretly think they deserve.

We can fix the problem. But first we need to see it. And to see it, we need to ask ourselves a seemingly dumb sounding question at the putative dating stage. When we are alone, when we contemplate our lives without anyone by our side, we should ask: How lucky would someone be to be with you?

And if our answer is, ‘Not lucky at all, because I’m a piece of shit, I’m horrifically ugly, I don’t deserve to be here’, then the problem isn’t really about us, it’s about those who first saw us and how unwell they were.

Every human being is up for differing kinds of interpretation. There is both marvellousness and awfulness in everyone. How we choose to read ourselves is always a choice, not a divinely ordained fact. So, if we view ourselves as wretches, it is only because others – cruel others – chose to read us that way in the distant past.

The difference between a flourishing and a self-hating life (and possible suicide) lies in the confidence we have in ourselves. Learning how to feel worthy of love, especially if it was denied to us early on, may be the hardest and most vital work of all. We need to understand what has happened – and take immense care.

Imagine if one day we were to ask: How lucky would someone be to be with you? And the answer came back from inside: Very lucky indeed. That might be the work, and the achievement, of a lifetime.