Self-Knowledge • Trauma & Childhood

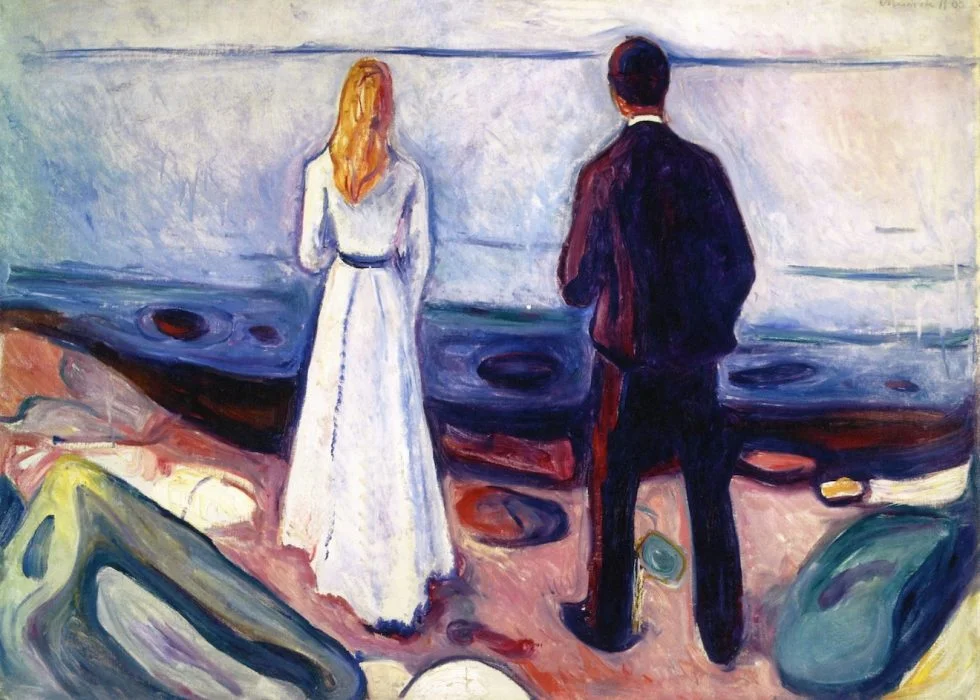

Why Everyone We Could Love Will Be Mad

Early on in our pursuit of love, we put it down to accident. We were unlucky. This or that one was randomly ‘off the rails’ or ‘slightly crazy’. It can take a long while to understand that the problem is endemic – and that it points us towards a deeper truth about how childhood trauma affects adult relationships.

We can analyse the universal predisposition of our partners to what we can colloquially call ‘madness’ like this. All of us were brought up in unbalanced environments. All families of birth are cauldrons of disturbance. There is always something: a depressed mother or an angry father; a closeted sadist; a vengeful moralist. There was someone who couldn’t bear vulnerability or who needed exaggerated signs of purity or social success.

Little children are hardwired to adapt themselves to survive in challenging circumstances. Helpless and fragile for a long time, they have an innate sensitivity to what any family requires in order not kill or eject them – and so will develop ingenious strategies to draw in the affections of their flawed caregivers. They feel their way to whatever is needed in order to be housed and fed for that first crucial decade.

The Inheritance of Madness: How Childhood Trauma Affects Adult Relationships

In response to raging parents, they develop a manic capacity to smile weakly and please. To deal with a depressed mother, they become jokers. To negotiate a jealous father, they take early retirement from success. To handle a bully, they become hypersensitive. They are as ill as they need to be to gain the sympathy of a parent who only gives kindness to the sick. In order not to be broken by a suicidal or alcoholic parent, they develop a capacity not feel any of their feelings.

These moves are – let’s put it plainly – strategies of near genius. At an age when these children can’t even write their own name or do basic arithmetic, some part of their brain will have worked out how to appease a complicated adult many times their size; some part of them will know they need to be ‘difficult’ in order not to be forgotten, or agree with everything so as not to be murdered.

We can applaud such strategies – and yet still recognise that they are the root cause of most of the difficulties we encounter around their grown-up selves. The follies of our partners can be understood in a simple dictum: they are the result of people continuing to do in grown-up environments what it was necessary for them to do to survive their childhoods. They are the result of adaptive strategies enduring in contexts that resolutely don’t call for them. They are the outcome of people continuing to disassociate where emotional presence would be called for, or continuing to be evasive when forthrightness would be key.

Learning to Thank Our Younger Selves

To unwind these strategies, we need – collectively – a non-pejorative awareness of their existence. We need to ask ourselves without shame what the ‘craziest’ elements of our behaviour might be and accept that – almost certainly – these will bear the legacy of some form of early strategy for survival. If we are overly worried about our appearance or our income, if we drink too much or can’t trust anyone, it will almost certainly be because these counterproductive moves were once key to our safety. We need to learn to thank our younger selves for their ingenuity and then try something new.

The scene is set for more interesting conversations on dinner dates. We should learn to ask: what ingenious but complex moves did you need to pull off to get through your childhood? And then: how might your strategies from back then be interfering with a successful or calm adult life now?

Obviously, it’s easier to talk about skiing or wine, but we should run if no answers at all are forthcoming. None of us can be entirely sane; the best we can aim for is a knowledge of the structure of our insanities, an understanding of how childhood trauma affects adult relationships, and a willingness to discuss these without shame or defensiveness with a curious and kind interlocutor.

We need, above all, to realise that what assured us love in the early years has a very high chance of being the very thing that will doom love for us henceforth.