Leisure • Sociology

Emile Durkheim

Emile Durkheim is the philosopher who can best help us to understand why Capitalism makes us richer and yet frequently more miserable; even – far too often – suicidal.

He was born in 1858 in the little French town of Epinal, near the German border. His family were devout Jews. Durkheim himself did not believe in God, but he was always fascinated by, and sympathetic to, religion. He was a clever student. He studied at the elite Ecole Normale Supérieure in Paris, travelled for a while in Germany, then took a university job in Bordeaux. He got married. There were two children: Marie and André. Before he was forty, Durkheim was appointed to a powerful and prestigious position as a professor at the Sorbonne. He had status and honours, but his mind remained unconventional and his curiosity insatiable. He died of a stroke in 1917.

Camille Pissarro, The Boulevard Montmartre at Night, 1897

Durkheim lived through the immense, rapid transformation of France from a largely traditional agricultural society to an urban, industrial economy. He could see that his country was getting richer, that Capitalism was extraordinarily productive and, in certain ways, liberating. But what particularly struck him, and became the focus of his entire career, were the psychological costs of Capitalism. The economic system might have created an entire new middle class, but it was doing something very peculiar to people’s minds. It was – quite literally – driving them to suicide in ever increasing numbers.

This was the immense insight unveiled in Durkheim’s most important work, Suicide, published in 1897. The book chronicled a remarkable and tragic discovery: that suicide rates seem to shoot up once a nation becomes industrialised and Consumer Capitalism takes hold. Durkheim observed that the suicide rate in the Britain of his day was double that of Italy; but in even richer and more advanced Denmark, it was four times higher than in the UK. Furthermore, suicide rates were much higher amongst the educated than the uneducated; much higher in Protestant than in Catholic countries; and much higher among the middle classes than among the poor.

Edouard Manet, The Suicide, 1877

Durkheim’s focus on suicide was intended to shed light on a more general level of unhappiness and despair at large in society. Suicide was the horrific tip of the iceberg of mental distress created by Capitalism.

Across his career, Durkheim tried to explain why people had become so unhappy in modern societies, even though they had more opportunities and access to goods in quantities that their ancestors could never have dreamt of. He isolated five crucial factors:

1. Individualism

In traditional societies, people’s identities are closely tied to belonging to a clan or a class. Their beliefs and attitudes, their work and status follow automatically from the facts of their birth. Few choices are involved: a person might be a baker, a Lutheran, and married to their second cousin – without ever having made any self-conscious decisions for themselves. They could just step into the place created for them by their family and the existing fabric of society.

But under Capitalism, it is the individual (rather than the clan, or ‘society’ or the nation) that now chooses everything: what job to take, what religion to follow, who to marry… This ‘individualism’ forces us to be the authors of our own destinies. How our lives pan out becomes a reflection of our unique merits, skills and persistence.

Gustave Caillebotte, Young Man at his Window, 1875

If things go well, we can take all the credit. But if things go badly, it is crueller than ever before, for it means there is no one else to blame. We have to shoulder the full responsibility. We aren’t just unlucky any more, we have chosen and have messed up. Individualism ushers in a disinclination to admit to any sort of role for luck or chance in life. Failure becomes a terrible judgement upon oneself. This is the particular burden of life in modern Capitalism.

2. Excessive hope

Capitalism raises our hopes. Everyone – with enough effort – can become the boss. Everyone should think big. You are not trapped by the past – Capitalism says – you are free to remake your life. Advertising stokes ambition by showing us limitless luxury that we could (if we play our cards right) secure very soon. The opportunities grow enormous…as do the possibilities for disappointment.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Hangover, 1889

Envy grows rife. One becomes deeply dissatisfied with one’s lot, not because it is objectively awful but because of tormenting thoughts about all that is almost (but not quite) within reach.

The cheery, boosterish side of Capitalism attracted Durkheim’s particular ire. In his view, modern societies struggle to admit that life is often quite simply painful and sad. Our tendencies to grief and sorrow are made to look like signs of failure rather than, as should be the case, a fair response to the arduous facts of the human condition.

3. We have too much freedom

One of the complaints against traditional societies – strongly voiced in Romantic literature – was that people needed more ‘freedom’. Rebellious types complained there were far too many social norms: telling you what to wear, what you were supposed to do on Sunday afternoons, what parts of an arm it was respectable for a woman to reveal…

Edouard Manet, The Luncheon on the Grass, 1862-3

Capitalism – following the earlier efforts of Romantic rebels – relentlessly undermined social norms. States became more complex, more anonymous and more diverse. People didn’t have so much in common with each other any more. The rules or norms that one had internalised stopped applying.

What kind of career should you have? Where should you live? What kind of holiday should you go on? What is a marriage supposed to be like? How should you bring up children? Under Capitalism, the collective answers get weaker, less specific. There’s a lot of reliance on the phrase: ‘whatever works for you.’ Which sounds friendly but also means that society doesn’t much care what you do and doesn’t feel confident it has good answers to the big questions of your life.

In very confident moments we like to think of ourselves as fully up to the task of reinventing life, or working everything out for ourselves. But, in reality, as Durkheim knew, we are often simply too tired, too busy, too uncertain – and there is nowhere to turn.

4. Atheism

Durkheim was himself an atheist, but he worried that religion had become implausible just as its communal side would have been most necessary to repair the fraying social fabric. Despite its factual errors, Durkheim appreciated the sense of community that religion offered: “Religion gave men a perception of a world beyond this earth where everything would be rectified; this prospect made inequalities less noticeable, it stopped men from feeling aggrieved.”

Marx had disliked religion because he thought it made people too ready to accept inequality. It was an ‘opiate’ that dulled the pain and sapped the will. But this criticism was founded on a conviction that it would not actually be too difficult to make an equal world and therefore that the opiate could be lifted without trouble.

Durkheim took the darker view that inequality would be very hard to eradicate (perhaps impossible), so we would have to learn, somehow, to live with it. This led him to a warmer appreciation of any ideas that could soften the psychological blows of reality.

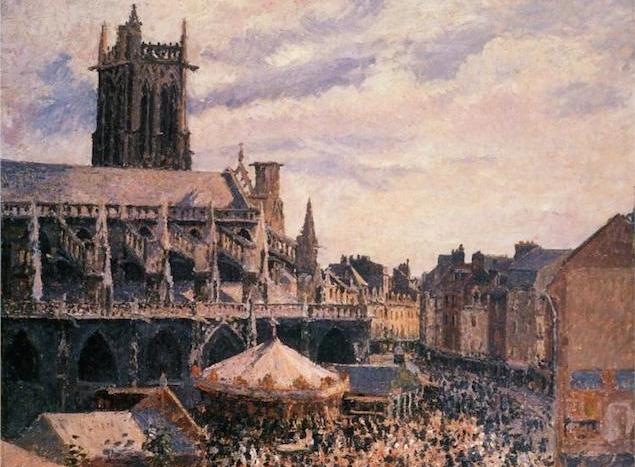

Camille Pissarro, The Fair by the Church of Saint-Jacques, Dieppe, 1901

Durkheim also saw that religion created deep bonds between people. The king and the peasant worshipped the same God, they prayed in the same building using the same words. They were offered precisely the same sacraments. Riches, status and power were of no direct spiritual value.

Capitalism had nothing to replace this with. Science certainly did not offer the same opportunities for powerful shared experiences. The Periodic Table might well possess transcendent beauty and be a marvel of intellectual elegance – but it couldn’t draw a society together around it.

Durkheim was especially taken with elaborate religious rituals that demand participation and create a strong sense of belonging. A tribe might worship its totem, men might undergo a complex process of initiation. The tragedy – in Durkheim’s eyes – was that we had done away with religion at precisely the time when we most needed its collective consoling dimensions and had nothing much to put in its place.

5. Weakening of the nation and of the family

In the 19th century, it had looked, at certain moments, as if the idea of the nation might grow so powerful and intense that it could take up the sense of belonging and shared devotion that once had been supplied by religion. Admittedly there were some heroic moments. In the war against Napoleon, for instance, the Prussians had developed a dramatic all-encompassing cult of the Fatherland. But the excitement of a nation at war had, Durkheim saw, failed to translate into anything very impressive in peacetime.

Family might similarly seem to offer the experience of belonging that we needed. But Durkheim was unconvinced. We do indeed invest hugely in our families, but they are not as stable as we might hope. And they do not provide access to a wider community.

John Singer Sargent, The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882

Increasingly, the ‘family’ in the traditional expansive sense has ceased to exist. It boils down to the couple agreeing to live in the same house and look after one or two children for a while. But in adulthood these children do not expect to work alongside their parents; they don’t expect their social circle to overlap with their parents very much and don’t feel that their parent’s honour is in their hands.

Our looser, more individual sense of family isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It just means that it’s not well placed to take up the task of giving us a larger sense of belonging – of giving us the feeling that we are part of something more valuable than ourselves.

Conclusion

Durkheim is a master diagnostician of our ills. He shows us that modern economies put tremendous pressures on individuals, but leave us dangerously bereft of authoritative guidance and communal solace.

He didn’t feel capable of finding answers to the problems he identified but he knew that Capitalism would have to uncover them, or collapse. We are Durkheim’s heirs – and still have ahead of us the task he accorded us: to create new ways of belonging, to take some of the pressure off the individual, to find a correct balance between freedom and solidarity and to generate ideologies that allow us not to take our own failures so personally and sometimes so tragically.