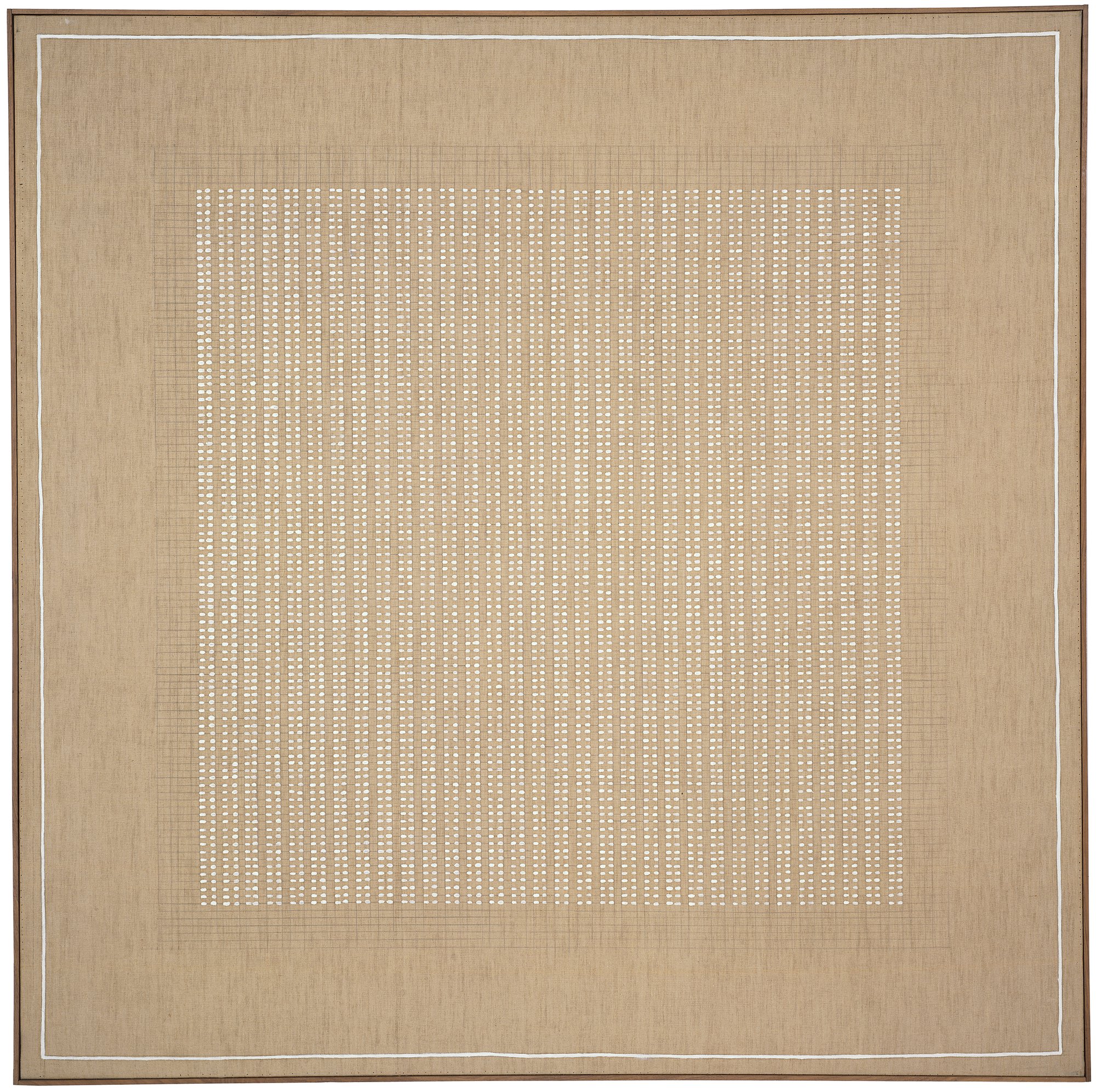

Calm • Serenity

Making Peace with Life’s Mystery

It’s typically assumed that the goal of any educated and ambitious person will be to try to understand ever more about everything: the wiser we are, the more we will strive to know. But there’s a contrary tradition in many philosophies and religions that points us to a very different and far more calming moral: that, at a certain moment, the wise will stop trying to understand who they are, why they are here and what everything means and surrender instead to ‘the ineffable,’ that which cannot be grasped by anything as limited and flawed as the human mind.

In their mystical branches, Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity, Judaism and Islam all stress that the greatest questions cannot be properly answered by human beings – and that silence and submission are the only fair ultimate responses to the ‘mysterium tremendum’, the awesome mystery at the heart of everything. We cannot possibly ever know our true purpose, the nature of existence, the role and relevance of the cosmos or the mind of God – and should not exhaust ourselves or offend truth by seeking to do so. In Mahayana Buddhism, ultimate reality – yogacara – is simply beyond articulation by an instrument as paltry as language; in Islam, the wise will capitulate to ‘al-Ghaib’ (الغيب), what is divinely ‘hidden’ and ‘incomprehensible,’ and the most pious Jews will not dare to utter the word ‘God’ from a sense that no human tongue should try to name ‘ein Sof’ (אין סוף), the power that is conclusively beyond fathoming.

Via the concept of the ineffable, we are – unusually and kindly – being given permission not to understand. Our not-knowing – who we are, why we have been placed here and what we should be doing – does not have to be equated with error or laziness; it can be evidence of the noblest kind of humility before the unnameable nature of ultimate reality.

When we come up against barriers to our comprehension, we do not have to rail against our blindness but – inspired by ancient philosophies – we can exchange fretful ambition for a serene resignation before the ungraspable beauty and complexity of all that we are fated by our limited minds never to be able to make sense of. We can at times willingly let go of our enervating pride – and admit – through our silence – that we simply and blessedly do not know.